In Hans Christian Anderson's fairy tale, when mermaids die, they dissolve into sea foam because they have no souls.

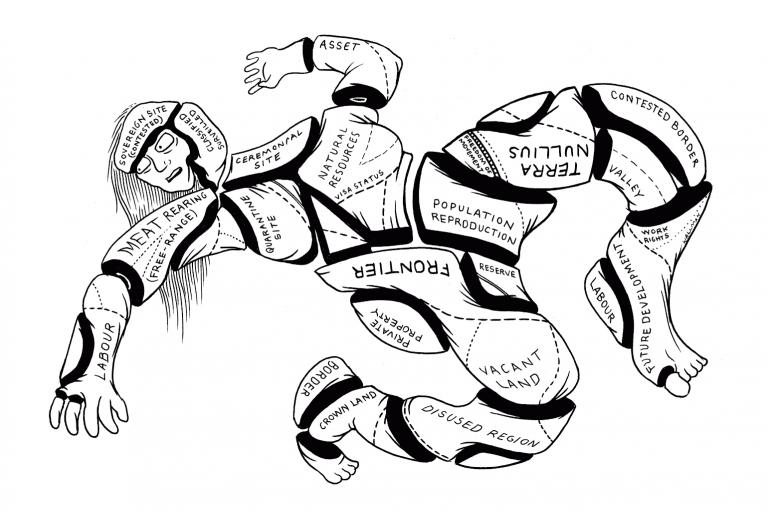

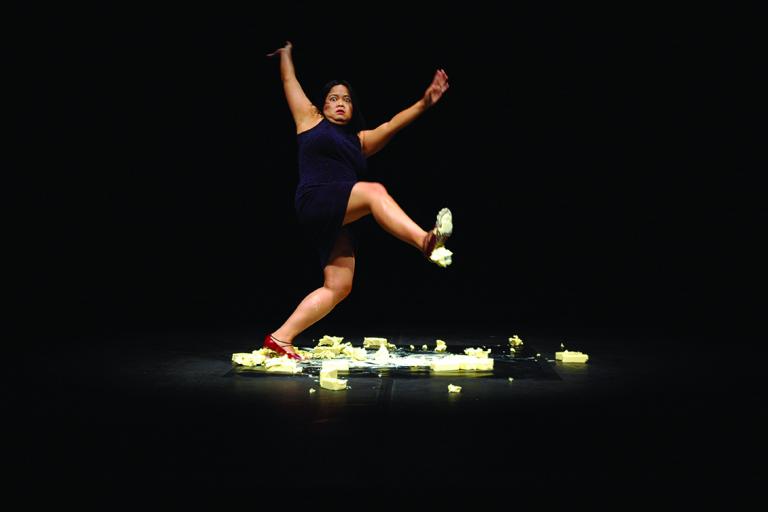

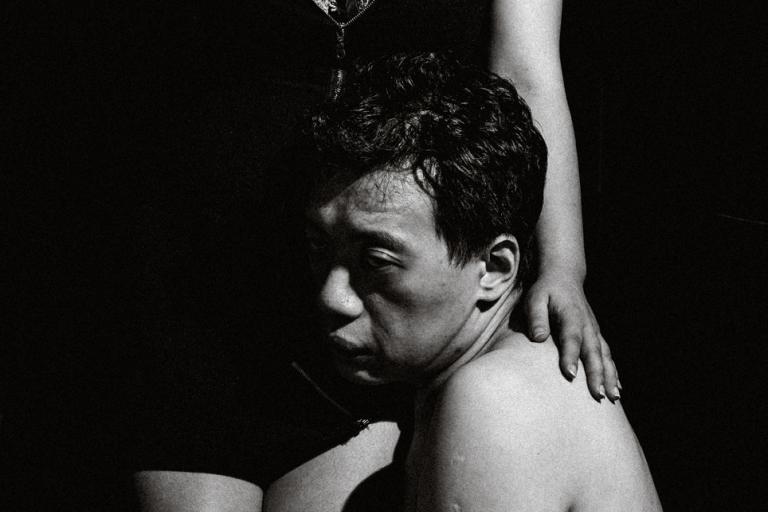

Disney left that part out like they left out where The Little Mermaid's bewitched feet made it feel like every step she took was on knives, but she danced a lot anyway. Seafoam is basically the same stuff you find in hot tubs: a frothy compound of organic matter and dirt, whipped protein, and particles. In Whitney Vangrin's performance piece Sea Foam, she prepares a mat of white sheet foam by spreading a big tub of lard all over it and then soaking it — and, ultimately, her white tank top-, white jeans-clad self — with a plastic bottle-full of ocean water, complete with sand and bits of seaweed. As an ethereal electro-vocal track rises, she begins a sliding, swaying, moonwalk-like 'dance' that evolves into full-body writhing on the mat. She repeatedly throws herself down onto it with enough force to turn her back bright red and even bloody, as if she were herself the kinetic energy that would generate spume out of basic elements. As her thrashing gets more violent, the recorded sound grows steadily darker and more heavily rhythmic.

It's not surprising that Vangrin is noted to have been influenced by the ecstatic religious dances of Shakers. [1] There are also some definite parallels with tarantism, probably most explicitly in Heel Yourself, a 2014 project by Raúl De Nieves, in which 20 vinyl copies of ABBA's 1979 hit "Voulez-Vous" were mixed simultaneously on 20 turntables, while Vangrin and another performance artist "engaged in rigorous movement atop sheet foam and salt". During the performance, Vangrin allowed long ropes of saliva to hang from her mouth — her body, in a sense, reacting to the context by visibly producing its own material. The Tarantella is a frenetic traditional Southern Italian dance which folklore held to be caused by (and also the cure of) the bite of a wolf spider known popularly as 'tarantula'. Musicians appeared on the scene as paramedics; fast rhythmic music gradually coaxed prone, jerking victims from the ground, and they would dance, sometimes for days, to purge the poison. Scientifically speaking, wolf spider bites don't actually cause dance trances. The tradition is now widely seen as having been a ritual for processing psychological stress or pain — a social, somatic therapy that was, significantly, embedded within the local community rather than directed by institutions or the state. The advent of neo-tarantism in the late 90s saw the practice moved more to the stage (often for tourists), causing local debate about the social implications of this shift. [2] There are certainly complexities around perceptions of who is deemed to be a passive viewer versus active participant in a given ritual or performance, but regardless of terminology, the relationship between these positions is porous. In a 2015 conversation with Genesis P-Orridge, Vangrin described, "A friend just mentioned to me that a gesture performance where I wept for five minutes made her realize she was sad." [3]

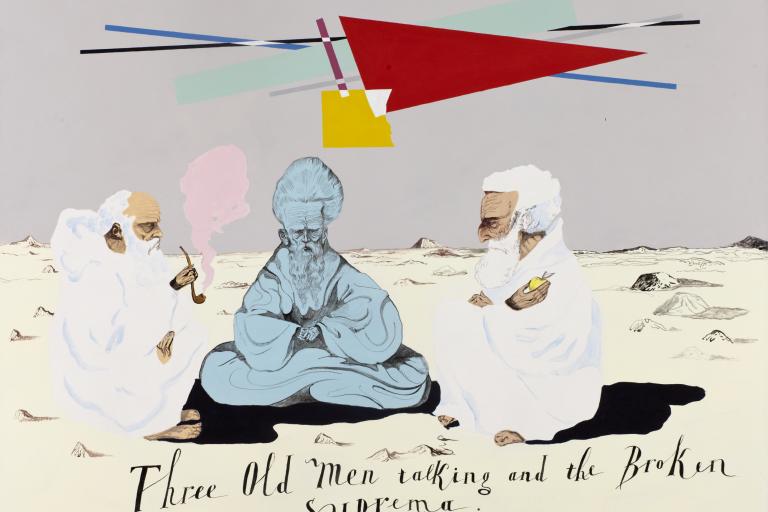

To pluck out another relevant thread from the social development of performance, about 20 years ago, an academic named Sarah R. Cohen published a paper arguing for the re-evaluation of some of the Rococo painter Antoine Watteau's figural drawings, based on acknowledging "a preoccupation in early eighteenth-century French culture with the construction of the body as spectacle". [4] This preoccupation hinged on an evolving distinction between ballet and tragedy — the latter being both languages- and narrative-based while, as Cohen noted in reference to how ballet moved from a court ritual out into wide and varied social consumption: "An early eighteenth-century viewer might go so far as to claim that no context at all was needed for the production of meaning in corporeal performance." [5] Cohen refers to a writer of the time for support: "The abbe Du Bos, for example, reasoned that although the music and dance of his own era did not convey dramas as the ancient pantomimes had done, they could still project meaning by simulating diverse 'characters', or states of being; directly addressing the imagination, the varied 'characters' of music and dance could endlessly stimulate a spectator's creative and emotional response." [6]

While Vangrin's work is obviously not character-based, it seems very related to states of being. If she cries for five minutes, it's going to be impossible to put any definite quantitative or qualitative value on the degree to which she is performing sadness and the degree to which she is, at that moment, feeling sad. When she rubs her entire body back-and-forth across giant ice blocks in Tongue in Ice, there's no doubt she's experiencing significant coldness and wetness, and this may prompt a visceral response in someone watching her. When, in the same piece, her repetitive counting takes on pre-orgasmic accents as she slides, her arousal (apparent and/or 'sincere') might turn people on. The experience of one body influences that of another. While 18th-century France may have been more concerned with the effects of virtuosity, Vangrin's work often prompts questions about how perceptions of authenticity can determine the degree of this influence.

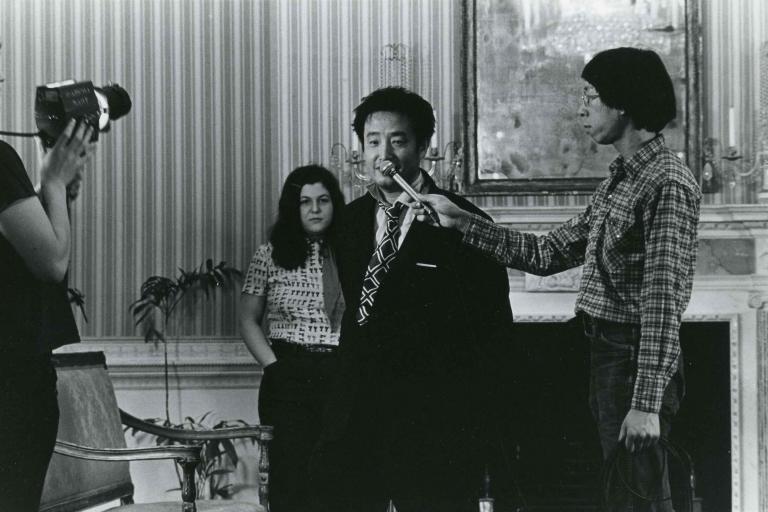

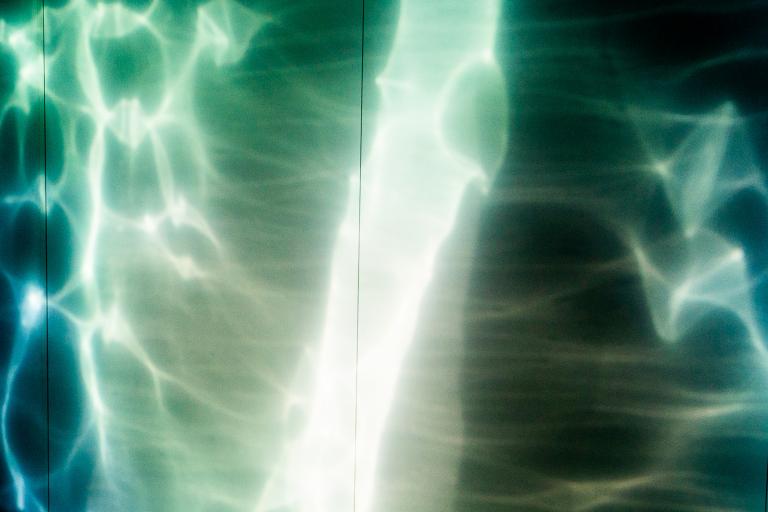

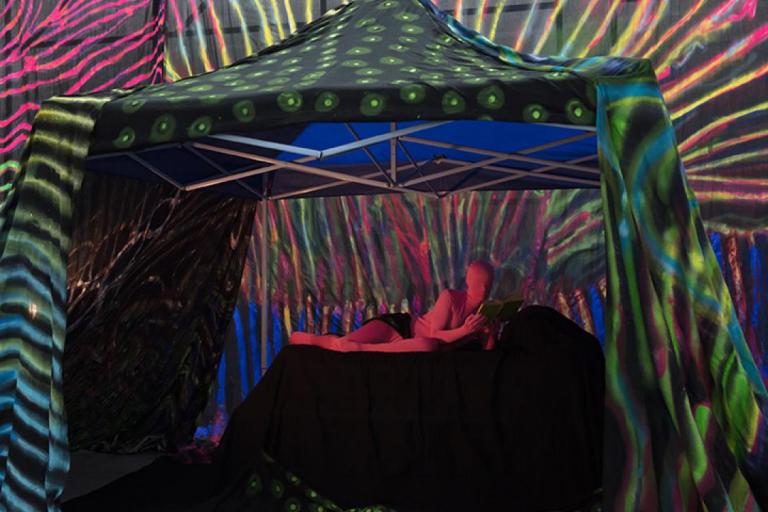

For those whose physical bodies don't intersect with Vangrin's, many of her performances are online; her Vimeo is well-stocked. She also creates video art, and often these modes fuse. In her live performances of Pump Screen and its precursor Inflate Tube, she uses a real-time streaming video feedback loop to create psychedelic trails and infinite iterations of herself staring fixedly into the camera/screen, spritzing herself with water till she is dripping, and periodically lip-syncing to the nostalgic Americana-esque songs woven into a pre-recorded soundtrack. This arrangement is writ large in Tangerine Blue, which was performed in 2016 at MoMA PS1's VW Dome, where live footage of herself was projected onto the curved ceiling at a scale of multiple feet and flanked by footage she had shot in California and New York. Elsewhere, in terms of recording devices, in Sand and Tar, she uses a small mic to electronically amplify the sound of various substances interacting with her body — nails on sandpaper, water in mouth, mic against teeth. Attending a live performance is not equivalent to watching/hearing an online video. Video does not transmit air that has been cooled by huge blocks of ice or, necessarily, the quiet squelching of wet foam. But, particularly as Vangrin's own practice straddles and conflates live art and recorded digital work, it's worth questioning strictly hierarchical relationships between 'original' and 'documentation'. In Mechtild Widrich's recently published book, Performative Monuments: The Rematerialisation of Public Art, she makes a case for performance as a kind of social monument that persists throughout history precisely through its documentation. Widrich approaches this idea, via Robert Musil, through the German word for monument, 'dennkmal', which translates more literally to a 'mark for thinking'. "After the 'precarious', 'ephemeral' exhibition has ended," she states, "there remain individuals who remember having participated in or encountered the work, and documents and artifacts that recorded its presence." [7] And these, she furthermore claims, "partake in the creation and maintenance of its social goals". [8]

In Vangrin's 2014 performance Chocolate Counter, a distorted nostalgia reaches, fittingly, truly saccharine levels with echoey excerpts from the scores of films like Disney's Snow White and Alice in Wonderland, wafting in-and-out over a continuous chorus of songbirds. Vangrin spends about half an hour spreading melted chocolate across the entire surface of a long Formica countertop in Brooklyn's closed-down Sunview Luncheonette diner. She sometimes moves dreamily, sometimes with a more frenzied air, depending on what the soundtrack is doing. Liquid chocolate drips freely onto the floor as she pushes it back and forth along the counter. She then scrapes it all up again and spends the next half-hour cleaning everything, seemingly as quickly as possible and with some palpable anxiety, but using only dish soap and paper towels. The work is reminiscent of both Oscar Murillo's 2014 exhibition at David Zwriner, A Mercantile Novel, and Kara Walker's major 2014 show, A Subtlety, in its examination of class, pleasure, consumption, material and immaterial labor, and the place of various bodies in the severely corroded underpinnings of the American Dream. Chocolate Counter is, in fact, based directly on a 1971 piece by Gina Pane, in which the performance artist dipped her hands into boiling chocolate as a way to personally process and publicly draw attention to the social indifference to the death of a drug addict. Vangrin told P-Orridge, "I think pain is a way to engage with the body and have others be aware of their engagement." [9]

Sugared, which debuted on Valentine's Day in 2016, is Vangrin's most direct engagement with pain and violence to date. Pulling together multiple elements from earlier works, it takes place in a small, darkened basement room. Again, Vangrin is embedded between lenses, screens, and projections. The spray bottle full of water is present to soak her gradually. Giant ice blocks have shrunk to cubes, which she rubs aggressively around her face and loudly crunches between her teeth. She slaps herself — pretty hard — on her iced-up face and thighs; she paces, pants, and laughs a maniacal 'haha ha' laugh. She chugs a beer, stalks back to the table, grabs another bottle, and smashes it on her head, eliciting startled gasps from the audience. At the end of the piece, she licks and fondles a third bottle before biting it to pieces. It's only on reflection and with the hint from the work's title that it becomes obvious the bottles are made of sugar. Vangrin performs an interesting sort of inversion. As life, through social media, becomes increasingly curated, controlled, and self-consciously presented, it's as if, even in the act of performing, she temporarily almost removes gaps between feelings and actions, as if the short-term states of consciousness she generates via her physical interactions with various substances could be fully inscribed and legible in the motion of her limbs. As sociologist Jeff Coulter details, a basically Cartesian mind-body dualism is still linguistically — and, therefore, deeply — entrenched in our self-perceptions; there is a significant difference between saying 'my face hurts' and saying 'I am in pain'. [10] The way Vangrin's art employs various materials to a degree collapses apparent divisions between mind and body. She appears immersed simultaneously in her physical sensations and emotions, as these continuously and fluidly impact one another. The affect does not feel reductively materialist anymore than she appears to have dematerialized. Rather, here, the very act of performing emphasizes how minds, bodies, and the meanings generated by them are socially embedded phenomena. In pointing to Wittgenstein as a productive guide for using social praxis as opposed to either materialism or mysticism to resolve dualism, Coulter quotes the philosopher: "The common behavior of mankind is the system of reference by which we interpret an unknown language." [11] Locating the individual somewhere, unsteadily, between the material and the communal invites a socially broad perspective. The rudimentary nature of Vangrin's cleaning implements in Chocolate Counter, for example, brings to the surface a question applicable across all the arts and becomes more pertinent the 'higher' you go: After the show is over and closed, who's cleaning up? The reflection might prompt further thought on souls and seafoam.

[1] "Opening". 2015. Arts Letters & Numbers.www.artslettersandnumbers.com/calendar/2015/8/26/opening.

[2] "Dancing The Spider: Tarantism And Transnationalism". 2008. In. St. John's: Canadian Society for Dance Studies. www.csds-sced.ca/English/Resources/JodiLundgren.pdf.

[3] "Genesis P. Orridge Talks With Whitney Vangrin About The History Of Performance Art | Topical Cream". 2016. Topicalcream.Info. www.topicalcream.info/editorial/genesis-p-orridge-talks-with-whitney-van...

[4] Cohen, Sarah R. 1996. "Body As "Character" In Early Eighteenth-Century French Art And Performance". The Art Bulletin 78 (3): 454.

[5] Ibid.,464.

[6] Ibid.,463. Emphasis added.

[7] Widrich, Mechtild, 2014, Performative Monuments, Manchester, United Kingdom: Manchester University Press. 3.

[8] Ibid.

[9] "Genesis P. Orridge Talks With Whitney Vangrin About The History Of Performance Art", Topical Cream, 2016, Topicalcream.Info. www.topicalcream.info/editorial/genesis-p-orridge-talks-with-whitney-van...

[10] Coulter, Jeff, 1993, "Materialist Conceptions Of Mind: A Reappraisal", Social Research, 60 (1).

[11] Ibid., 141.