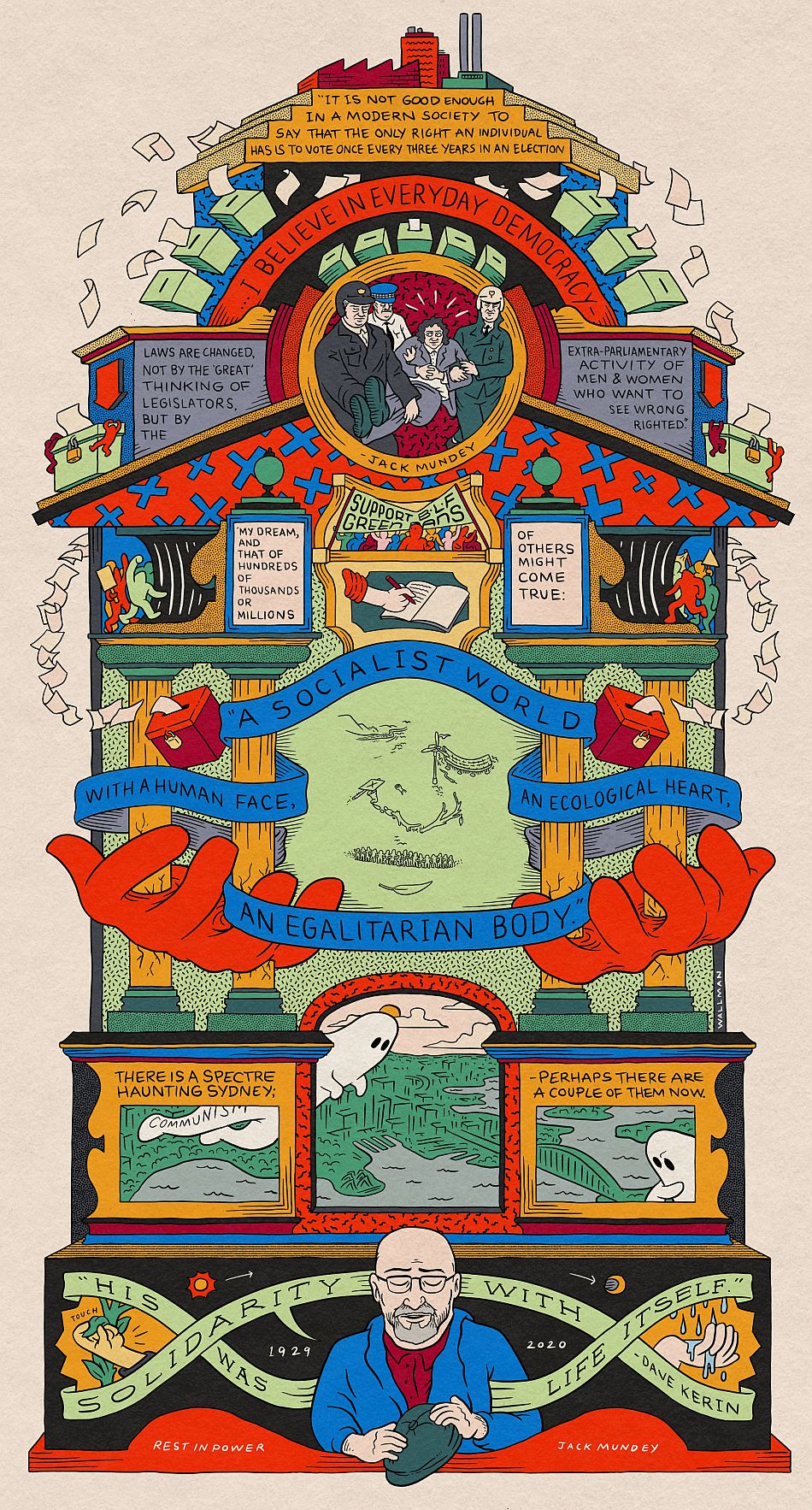

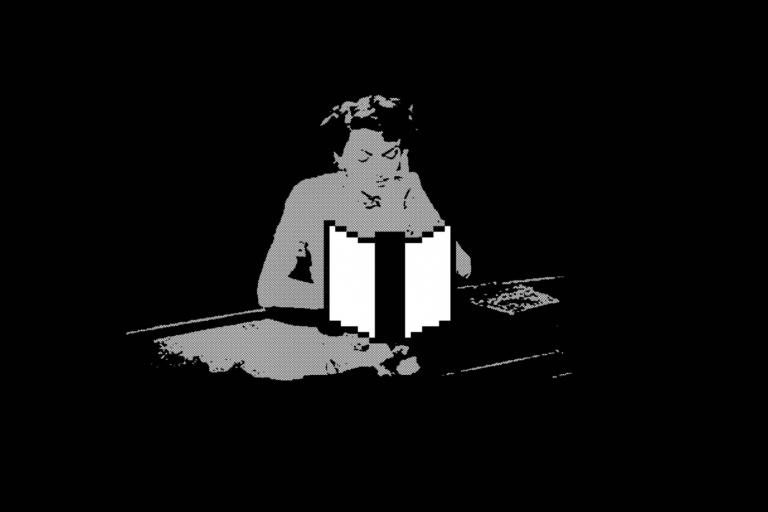

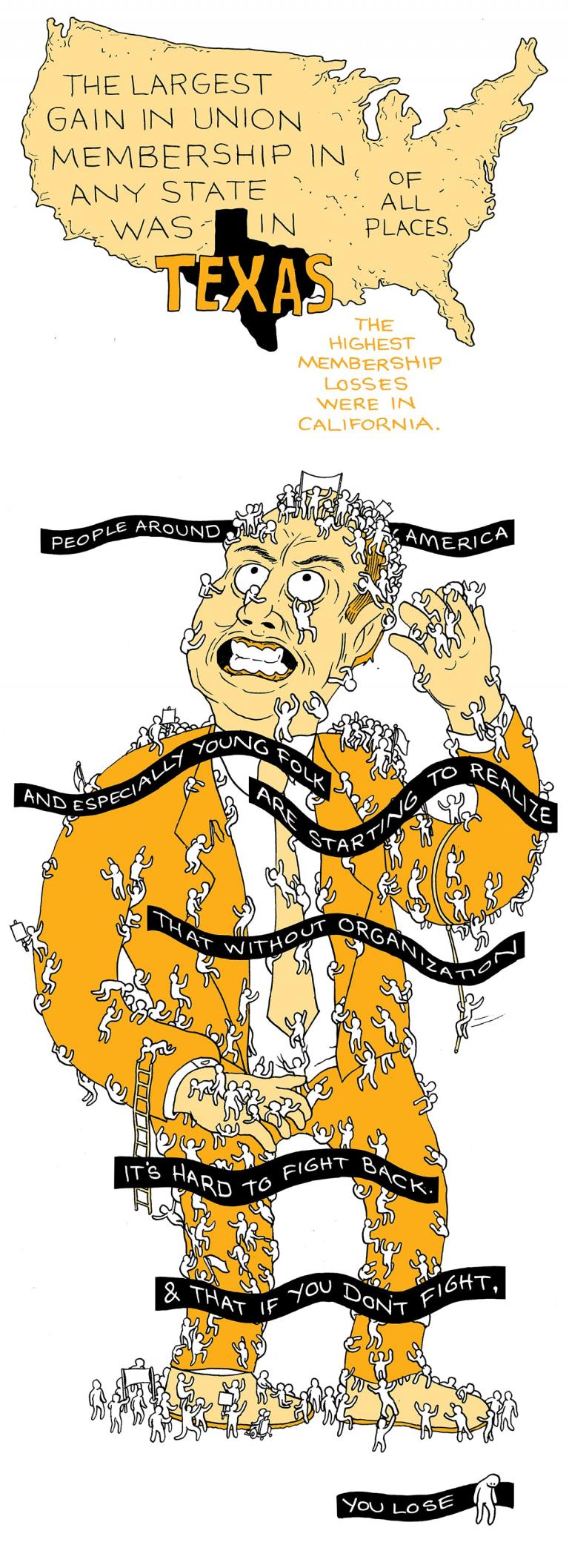

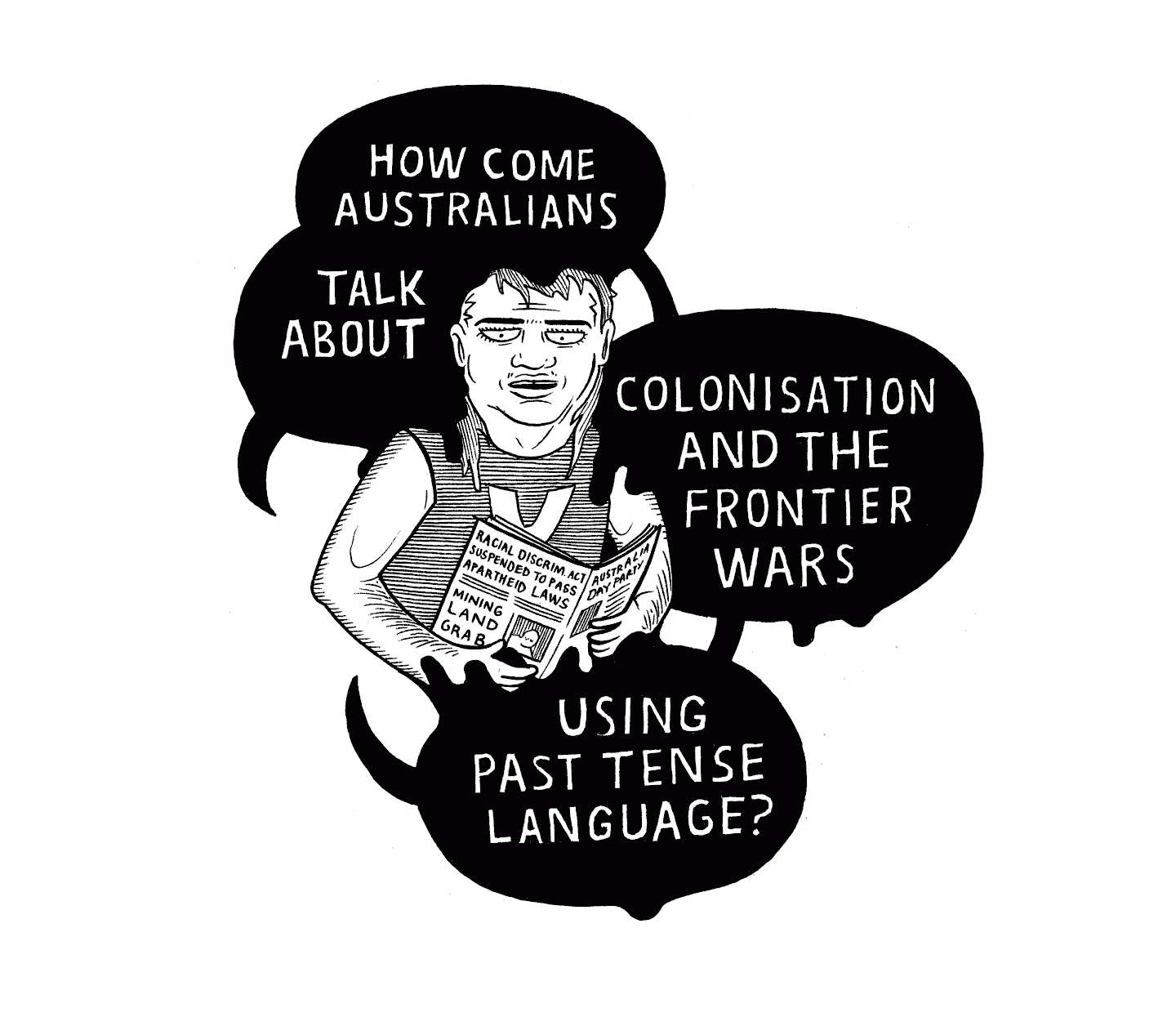

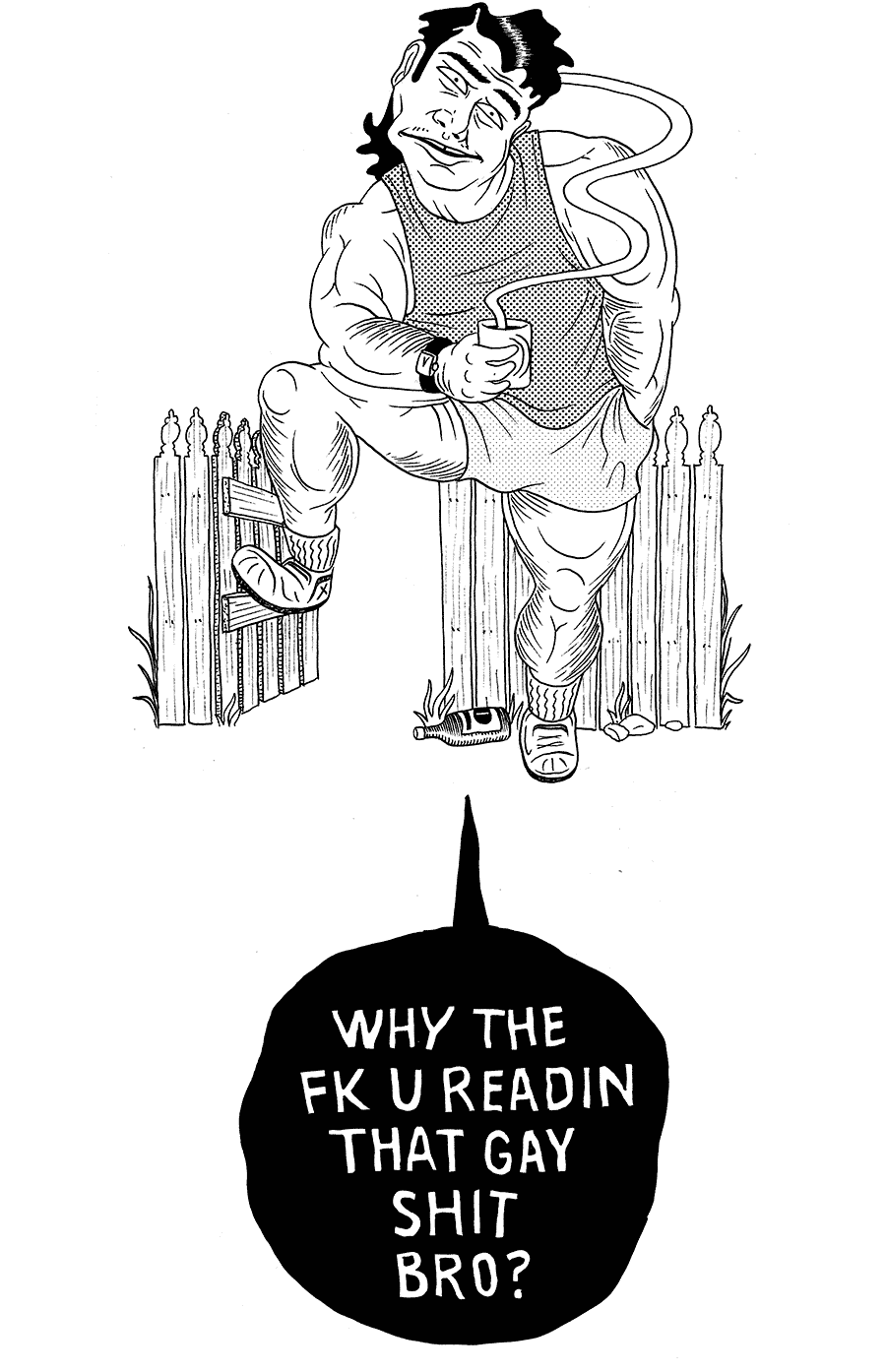

Sam Wallman's cartoon style is a disarming cross between Matt Groening and constructivist propaganda art. Often tragic in subject matter, his illustrations provide the visual comedy and playfulness needed to describe big social and political ideas without the artist (or his audience) breaking down into tears. The words spell it out, but you don't have to be able to read.

Wallman's comics go both large and very small, from printed zines or an image on a cell phone to blown-up comics painted across a real-life wall or a banner held high at a protest rally. He combines words and pictures in unusual ways to narrate his message, breaking many of the formal conventions of comics.

The greatest constant in Wallman's art is people — united groups of people — communities, families, workers. Their needs and desires are the focus and substance of most of his illustrations. His plastic cartoon figures represent human identity and aspiration. Complex ideas are delivered through visual metaphor and illusion. Individuals are depicted as part of the greater whole and humanity as a multitudinous single entity.

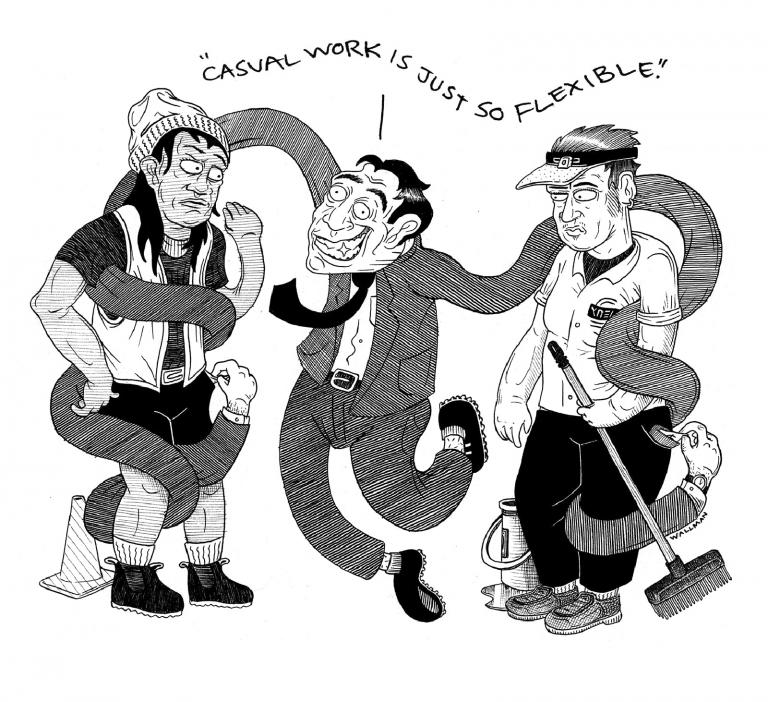

Many of Wallman's pictures create their own three-dimensional shape, helping to define the strip's physical boundaries within the page or screen. The illusion of dimension is turned inward on his characters' bodies as if bent and twisted by their economic and social relations to create the visual architecture of the comic itself. His images map out his social philosophy as clearly as any infographic, with the playful geometry of M.C. Escher.

Much of Wallman's approach to comics appears to come out of two distinct traditions born of the fertile 1990s when children's comic books in the US became unprofitable, and a myriad of new adult genres began to take hold. Among the influential graphic novelists to emerge from this period were Joe Sacco and Scott McCloud. Sacco created ground-breaking graphic novels built from eye-witness reporting of war zones. McCloud rose to fame as a comics artist and theorist who advocated for embracing technology in reinventing the medium.

Wallman employs Sacco's pioneering style of comics journalism to document the experiences of everyday people, from gay meth users to the guards of an immigration detention center. His characters embody the voices of primary sources, bringing documentary narratives to life while detailing the reality of everyday human existence.

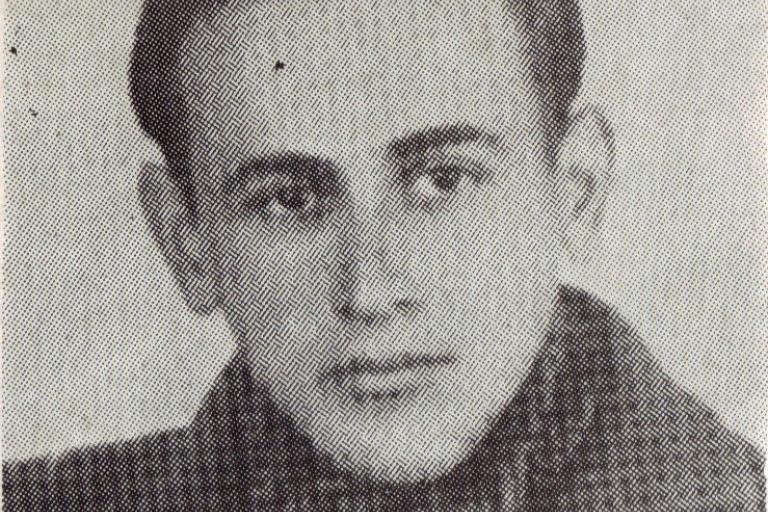

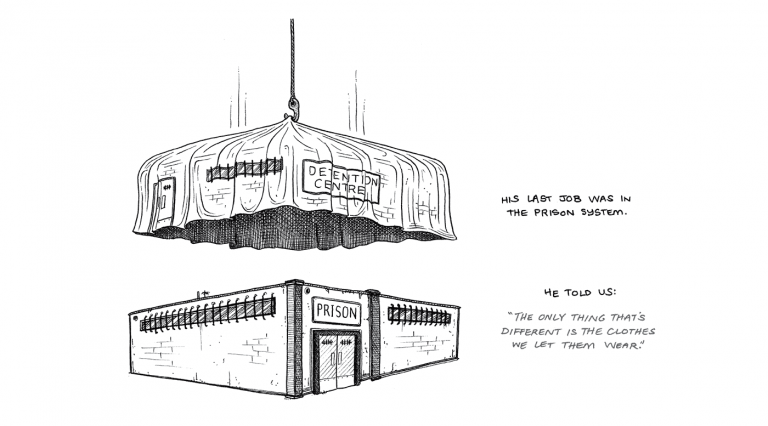

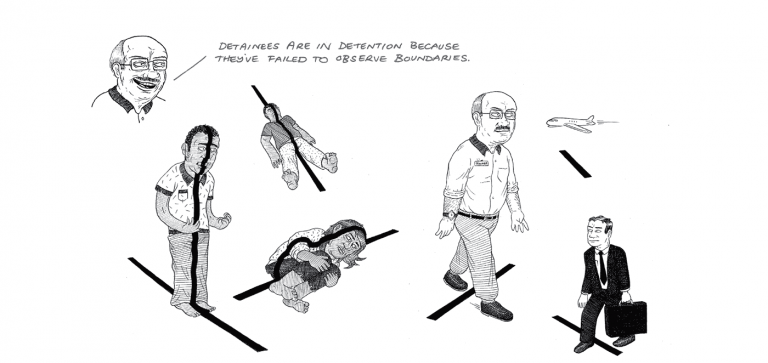

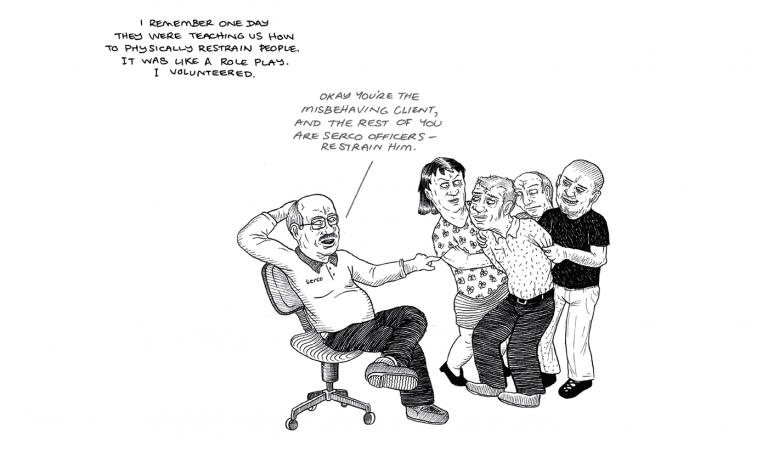

In 2014, he produced At Work Inside Our Detention Centres: A Guard’s Story with journalist Nick Olle and “producer” Pat Grant for the Global Mail, a non-profit news site sponsored by multi-millionaire philanthropist Graeme Wood. The collaborative work made it to publication within days of Wood pulling funding from the whole Global Mail project, making it one of the site's last and most lasting stories. The comic went viral and projected Wallman to international prominence.

A Guard’s Story follows the first-hand account of a worker at a Serco-run immigration detention center, from recruitment through to his disillusionment and resignation. “They hire people quickly and in big groups,” the protagonist tells us. “You don’t have to have qualifications or anything.”

A training instructor explains to the recruits: "If we didn't protect our borders, we'd have a massive flow of people into the country, and our quality of life would decline.”

Once on the job, the so-called dangerous law-breaking detainees are revealed to the guard to be no more than deeply depressed and traumatized asylum seekers, trapped in a cruel system that has no interest in their well-being or addressing their claims. The comic relays in harrowing detail the anguish and suffering of these detainees, referred to as “clients” by the corporation. It also describes the damaging effects of the center on the mental health of the worker himself. Through a combination of investigative research and direct undercover reporting, Wallman’s comic critiques the structures that allow and encourage such deeply dehumanizing experiences to proliferate in Australia’s immigration detention facilities.

“Australia has one of the most privatized prison systems on the planet,” Wallman explained to me. “Every single one of the country’s immigration detention centers is run by a large multinational corporation, rather than the government… There are people whose superannuation funds profit from the asylum seeker industry.”

The plight of refugees is a key concern for the artist, who has described the anti-immigrant and anti-Muslim cartoonists of Charlie Hebdo as “racist dickheads”. These cartoonists, Wallman says, are giving political cartoonists a bad name through their use of calcified stereotypical tropes and visual metaphors. Compared to the nuanced discussions of race, class, and immigration in Wallman's comics, you can see why he'd say that about the infamous Hebdo drawings.

Much of the effectiveness of A Guard's Story comes from the medium itself — the medium of the web. Wallman's online visual narratives embrace the sort of extended canvases that Scott McCloud imagined in his theoretical and practical experiments with webcomics, first pitched in his book-length graphic essay Reinventing Comics back in 2000.

The elements of frames, icons, speech bubbles, captions, and glyphs, essentially derived from comics, have come to dominate the language of computer interfaces and the internet. Wallman explores the pervasiveness of the language of comics in his visual essay, “What implication does the emoji have for the future of linguistics?”

"I see my practice coming from the same lineage as hieroglyphics,” he writes, “and from people in the 1800s explaining political ideas through images and metaphors when the broader population wasn't able to read words.”

On the web, the act of turning pages is supplanted by scrolling vertically or swiping left and right. Some of Wallman’s most powerful narratives are those in which he harnesses the medium with unusual fluency. Scott McCloud once observed that a book's open pages synchronize with the landscape format of a reader's field of vision, as does the computer screen. The single portrait-style pages of traditional print comics do not communicate as clearly in this medium.

Print comics are dictated by the booklet's size and shape, as each page contains frames, borders, gutters, and sequences, left to right (or right to left in the case of Japanese manga). Whereas on the web, Wallman's cartoon sequences float in screens of white (or black) space, allowing the images to provide perspective and depth, as characters either fill the space or recede into an imagined distance. Or they stretch beyond the screen's frame entirely to continue their action vertically down the page as the user scrolls to no set end, with images undulating like the passing rail tracks of a train journey.

In So Below, he takes the reader on a journey down the page to the very earth beneath our feet. The comic explores ideas concerning the meaning of land, the horrors of concrete definition, division, property ownership, and indigenous concepts of belonging. Other online scrolling comics include Brick by Brick: Is This Europe?, about Eastern Europe's border camps; Who are you calling a Luddite?, exploring our love-hate relationship with technology; and Seed Water, a comic about water that literally flows down the page into the roots of the earth.

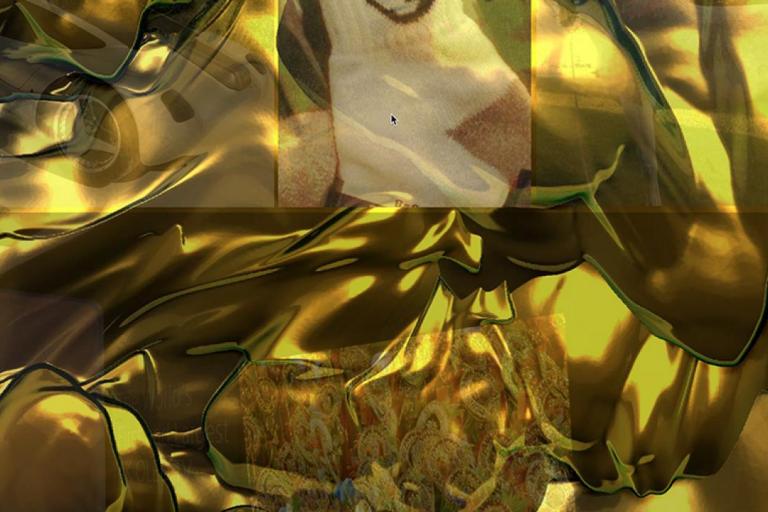

But Wallman is also a terrific pensmith. Despite their online conception, his cartoons have a hand-drawn quality that gives them their immediacy and power. The drawings in A Guard’s Story are created with real ink on paper, cross-hatched pen lines, and hand lettering — no electronic fonts.

Although his more recent comic essays are entirely digitally created, the artist explains: “There is something decidedly unromantic about digital artwork compared to pen and paper. I resisted it, but I'm able to pull off much more complex work using layers, mirrored canvases, and grids. I haven’t drawn anything on paper in many months. I am a true Procreate/tablet convert lately,” he says, referring to his device and program of preference. But then he adds: “I will never use digital fonts.”

The internet enables comics to travel the world, but when it comes to recording his subjects, Wallman prefers to encounter them in the flesh. He is a prolific traveler. Many of his documentary projects are based on boots-on-the-ground reporting from his journeys through Eastern Europe and the US. Some of Wallman's earliest cartoons were drawn on table napkins as he traveled through the Middle East.

“I’m very fortunate to have such a portable art form,” he says. “The works I have produced about the US and the UK have largely been from those places. I don’t think anything can take the place of on-the-ground research, face-to-face interviews, wherever possible.”

“Yesterday, I rode my bike to the base of the West Gate Bridge, and the sheer physicality of the thing will definitely help me draw about it — so much more than Google images.”

In 1970, Melbourne’s West Gate Bridge dramatically collapsed two years into construction, killing 35 workers in what remains Australia’s worst industrial accident. “I tried to see it, un-see it, see it again, and so on,” the artist explains.

In the run-up to the 2016 US Presidential elections, Wallman traveled to the United States, covering the campaign through the characters he met at rallies and on the streets. Among other things, the trip spawned his story A Covert Gaze at Conservative Gays, an exploration of the right-wing LGBTQ community in the US.

In recent times, Wallman has collaborated with animator Bailey Sharp to share stories of meth use in the Australian LBGTQ community in the Be-Longing For It project. “Bailey is amazing,” he says. “We also made an animation about the history of the Green Ban movement, which I’m quite proud of!” The Mighty Green Ban Movement is an animated polemic that traces the Australian labour movement’s little-known contribution to the development of green public spaces by municipal governments in cities worldwide. Building laborers would refuse to work on projects they viewed as environmentally or socially harmful.

Wallman still publishes many comics in regular print form, such as his 2015 collection Pen Erases Paper, and a 200-page graphic novel that he is currently writing, titled Our Members Be Unlimited, that explores the past, present, and future of organized labour. He worked as a picker at Amazon as research for the book.

In early 2020, Wallman contributed a story to Baltic comics magazine š!#37 about the Australian-US joint satellite surveillance base at Pine Gap, near Alice Springs. In 2014, Wallman edited Fluid Prejudice, a compilation of comics documenting little-known stories from Australian history, and in 2015 he co-edited Where Do I Belong? with Michael Fikaris and Safdar Ahmed for the Silent Army comic collective, a collection of visual storytelling from the voices of Australian refugees.

Wallman continues to be a regular participant in Australian zine festivals and a mentor to younger artists and writers in his hometown of Melbourne. He is a champion of the LGBTQ community – "I am a poofter,” he tells me bluntly.

Wallman’s role as a some-time trade union organizer for the National Union of Workers has also led the artist to write a bunch of trade union-associated comics. These include Union Membership is Finally Back On the Rise, explaining the reasons for the historical decline (and modern rise) of trade unionism in the United States — “Thank a young person!”; and “Labor Day” isn’t Labor Day, outlining the establishment's hijacking of the idea and symbolism of this working-class holiday. It’s deliberately not held on May 1st in most western countries, the comic tells us, in order to disconnect it from its socialist origins.

One of Wallman’s most moving pieces is a recent graphic tribute and memorial to Australian trade union stalwart Jack Mundey who died in May 2020, featured in the Overland, a left-wing online political journal for which he is associate editor and contributes regular articles and comics.

Like the contorted torsos of the human figures that populate his cartoons, Sam Wallman's art and activism remain firmly entwined.