*trigger warning for vegans

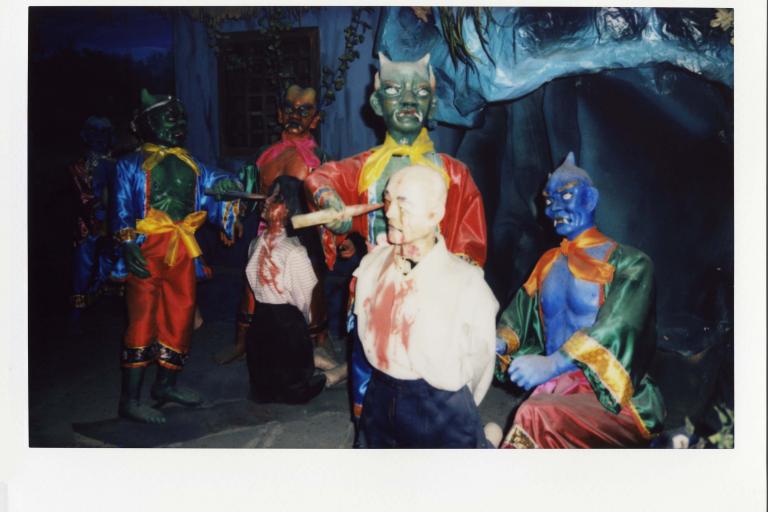

Reputationally, pigs get a raw deal. In the Old Testament, for instance, they are considered unclean. Even worse, one of the most well-known pig stories is in the Book of Matthew, where a legion of demons begs for a toasty warm vessel to inhabit after being cast out of their human host, so ask to enter a herd of innocent swine. After this, they proceed headlong off a steep bank into the sea, ending the poor, short lives of said pigs. A messy room is likened to a pigsty, and to eat ravenously is considered ‘eating like a pig’. In fact, not only are pigs clean animals who keep a healthy well-kept sty but they were born to eat like pigs do, without end, amen! But possibly the most undeserving of associations imposed upon pigs is through the use of their name in popular vernacular to refer to ‘police’.

None of these associations and stories afford these beautiful, intelligent, sentient creatures anything near the respect they deserve. In most instances, a pig’s common destiny is to provide human sustenance and other manifold products we take for granted, such as jelly, belts, jackets, and shoes. Squeezed into pens without the kind of space needed to keep their eating, sleeping, and defecating separate, they are susceptible to illness and distress. These associations, however, are nullified in the poignant work by performance artist Kalisolaite ʻUhila titled “Pigs in the Yard”. This work has had a couple of iterations in Aotearoa (New Zealand), where ʻUhila and his family live as part of the Tongan diaspora.

Throughout Oceania, the pig is sacred. In Tongan society, pigs have been treated with respect and deference because they represent wealth and social mobility. With an abundance of pigs, one can offer the animal to enter into discussions with the Tongan aristocracy and royal household, or one can present them as an offering or gift during special events such as public holidays, weddings, funerals, and birthdays; in Tongan tradition, a child’s first birthday is considered a major event. Every 4th of June, the Kingdom of Tonga celebrates its emancipation from the British Empire in 1970. The country’s national day is on November 4th. But the main event of the year is the birthday of the reigning monarch (currently Prince Tupotoʻa-ʻUlukalala). ʻUhila describes these celebrations during which the poor and wealthy alike offer up their pigs out of respect for the occasion. Pigs are cultural capital, a form of currency.

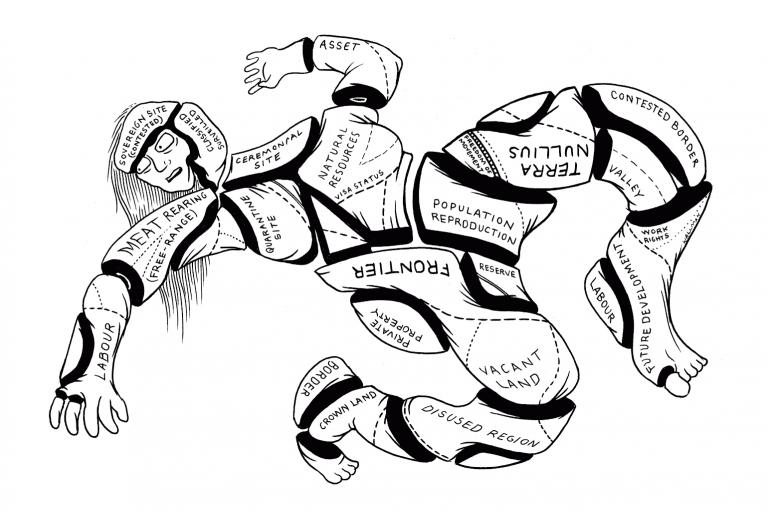

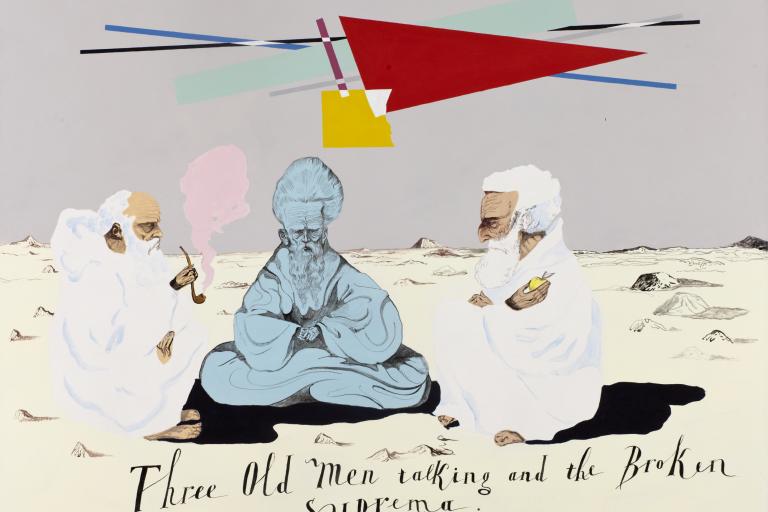

Through a Tongan lens, an entirely different association and treatment of pigs occurs. Roaming free, like the sacred cows of India, the pig plays a tacit role — a cross between a mayor and a martyr. ʻUhila’s work frees the pig of Western associations with piggeries, transforming a defined space into a deferential equalizer where pig and human share a common sty.

ʻUhila says that pigs are central to the culture of Tonga. He ascribes a human role to the pig, acknowledging this role as sacred and political, despite the pig's life ending as a sacrifice in the King’s court or a major family celebration. As in many Southeast Asian, non-Muslim diets, the pig is honoured in its sacrifice by ensuring that not a single part of its body goes to waste. From the ears to the snout, to its intestines and its trotters, no part of the creature is considered inedible, and its dying is never in vain. It is appreciated as sustenance in its entirety. In this same sense, the Moana-Oceania treatment of pigs takes a similar approach but for slightly different reasons: as a supernatural meal and offering.

There are numerous contextual elements specific to the rites involving pigs in Tonga within “Pigs in the Yard” itself. To begin with, ʻUhila’s pen-mate is a weaner pig. It is not large or oversized, which in terms of Tongan protocols, is permissible. Pigs that are too large to be carried by hand are considered tapu (sacred), and commoners are not permitted to own them. The work is a bold statement about the life of the common pig, especially as it was performed outside of the Tongan archipelago.

When “Pigs in the Yard” was first performed at the Mangere Arts Centre in South Auckland in early 2011, ʻUhila fenced himself and gallery-goers off from a herd of pigs he had released into the courtyard to experience freedoms they might enjoy if they were in Tonga; the humans were confined while the pigs roamed free. It was a powerful transgressive statement, which clearly delineated an alternate perspective of the sacrosanct ‘white cube’, occupying it as if it were on Tongan fonua (land).

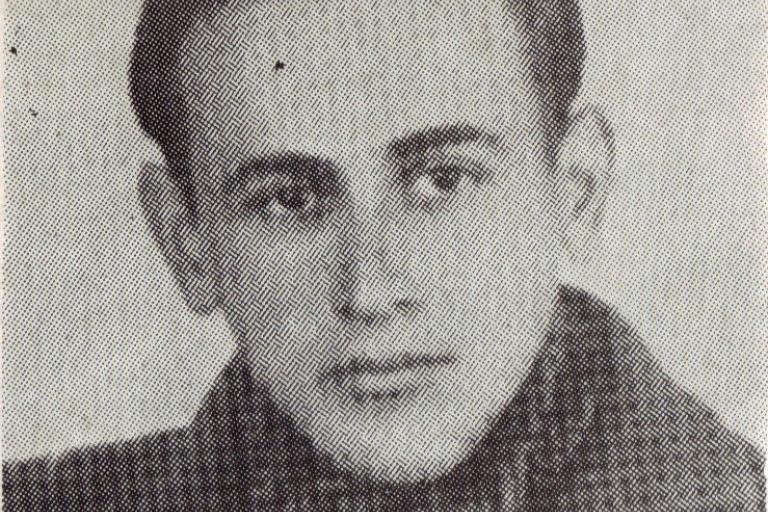

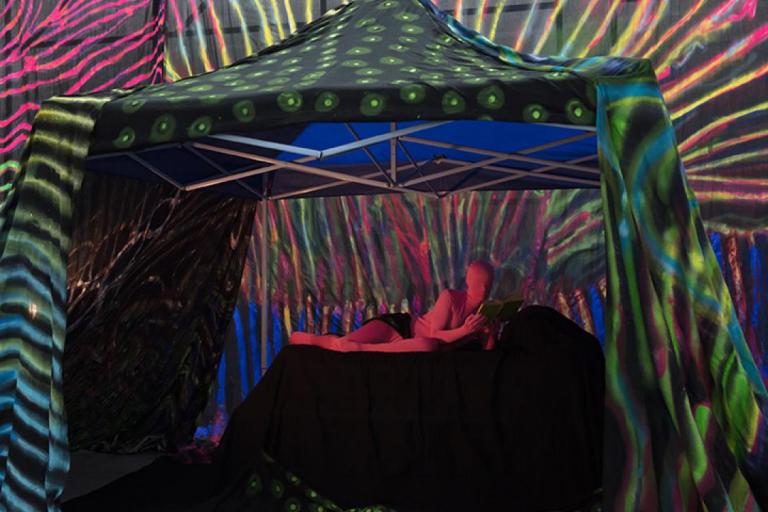

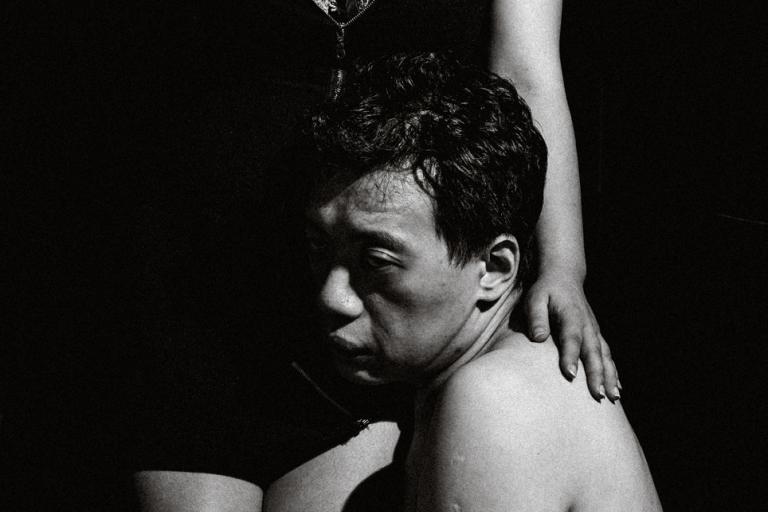

The second iteration of the work was for the 2011 Performance Arcade in Aotea Square, in downtown Auckland. ʻUhila turned an open shipping container into a pigpen for himself and one little pig friend. Here, ʻUhila took on every aspect of the pig’s life. For eight days, they shared the confines and grew to know each other intimately. To borrow a line from George Orwell’s Animal Farm, “They looked from pig to man and man to pig and could not see a difference.” One could argue that ʻUhila applies the trope of humans being no more important than pigs but in a Tongan relational sense. It is not him lowering himself to the lifestyle of a pig. Rather, it is him being afforded the privilege of accompanying the pig, which in this instance is the being of most importance to ʻUhila’s work.

In “Pigs in the Yard”, the artist is dressed only in a black lavalava and some pandanus adornments, typical in Tongan traditional attire. The shipping container was lined with black polythene, with a thick layer of hay placed on top to create some semblance of a barnyard and to provide comfort, safety, and space for the artist and the pig. They each had their own water basin and rested together, like siblings, on a shared piece of hessian. It is probably the first in-situ endurance performance work of its kind to be performed or enacted outside of a rural farming context, purposely bringing the rural feel of Tonga into the urban populous of the largest city in Aotearoa.

Speaking of the farm, according to the website Specialist Pig Practice, the general health of a pig can be diagnosed according to how they rest: whether their legs are tucked under them, indicating that they are cold, or legs outstretched, signaling comfort. The lower-status pigs will pile up to sleep, and the more dominant will sleep detached from the pile. The pig starring in the second iteration of “Pigs in the Yard” was also a weaner and still growing. Like any growing human baby, it required a lot of sleep. The photograph of ʻUhila and the pig sleeping next to each other indicates that they are of equal status in the pig hierarchy and that between them, there is an interdependence.

In “Pigs in the Yard”, ʻUhila sets aside his roles as husband and father, son and grandson, uncle and friend, to pay homage to one of his homeland’s sacrificial and sacred creatures. In casting all his home comforts aside to remember the unsung political beings that uphold the mana (spiritual power and status) of Tongan cultural traditions, ʻUhila elevates the pig to high art.