Aki Onda is not an occultist. Or at least not a professional one.

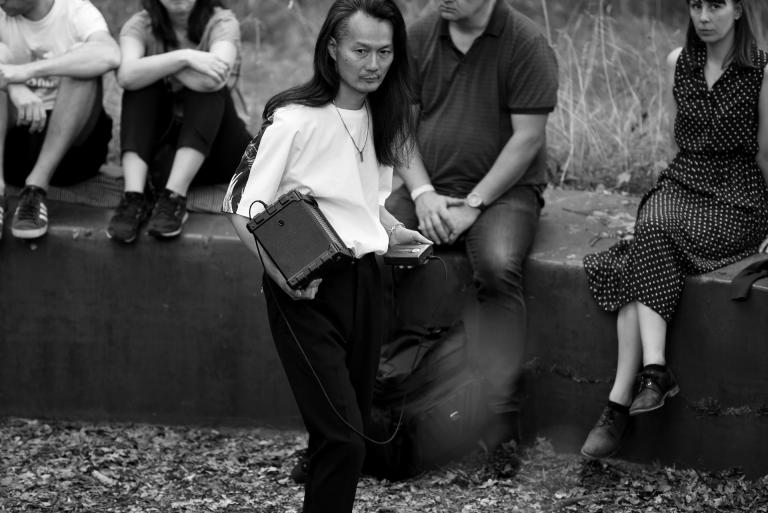

He stressed this more than once during a Skype interview in July 2020, just days before moving his home and studio from New York City — where he’s lived for the last 17 years — to Mito in the Japanese prefecture of Ibaraki.

“I’m not into being a cult star. A mystic is fine, but I hate being a cult star,” he said with a laugh — Onda laughs a lot in conversation — but emphatically all the same. “It doesn’t make much money, and it’s connected to being an authority.”

While he’s not a purveyor of the supernatural, Onda is open to such ideas. If he weren’t, he wouldn’t have made — or, rather, wouldn’t have been able to receive — his new album, a collection of messages from the late Korean artist Nam June Paik.

“I always have something that’s hard to explain with language,” he continued. “When I do a performance or when I make something, I always feel like it comes from somewhere else, and I don’t know what it is. It’s something spiritual — but like I said, I don’t like to mystify things. I want to leave it open and share it with other people. I have the system, and I know how it works, but it’s hard to explain.”

Onda’s systems aren’t any easier to explain for the observer. His art is as varied as it is unusual, from experimental projects with the likes of avant-garde cinema virtuoso Ken Jacobs and French jazz guitarist Noël Akchoté to atmospheric, improvised recordings with New York guitarist Alan Licht and Canadian sound- and filmmaker Michael Snow to film and photography, installation and performance.

And Onda, too, is an observer, a filmmaker and photographer, a curator, and a freeform documentarian. He deals more in ideas than forms or formats, and ideas come in different shapes and sizes.

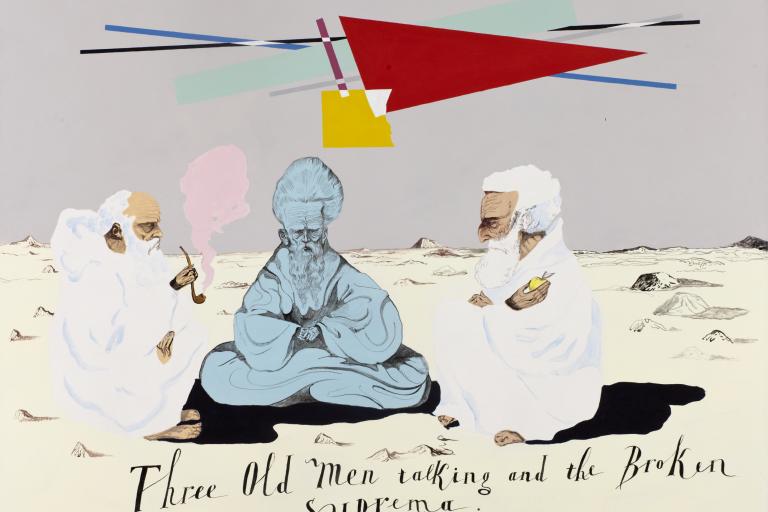

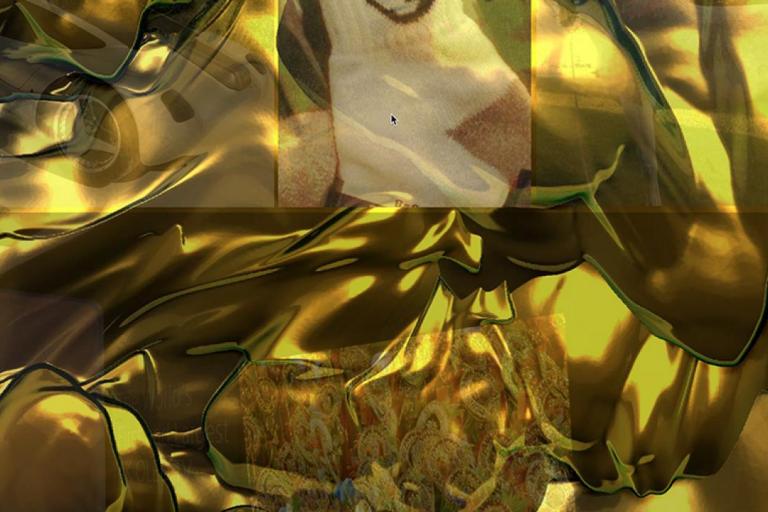

Which is where Nam June Paik comes in. Onda had long been an admirer of the multimedia artist Paik, whose work with the New York Fluxus school in the 1960s anticipated installation and video art, and in a sense, presaged Onda’s own, eclectic art.

“His work is always interdisciplinary; he always combines different media,” Onda said of Paik. “The way he used imagination interests me. He was really into TV. He can transport ideas, and he doesn’t really care if the meaning behind them changes. He’s elusive, hard to pin down. He uses pop culture, but sometimes his work is really esoteric.”

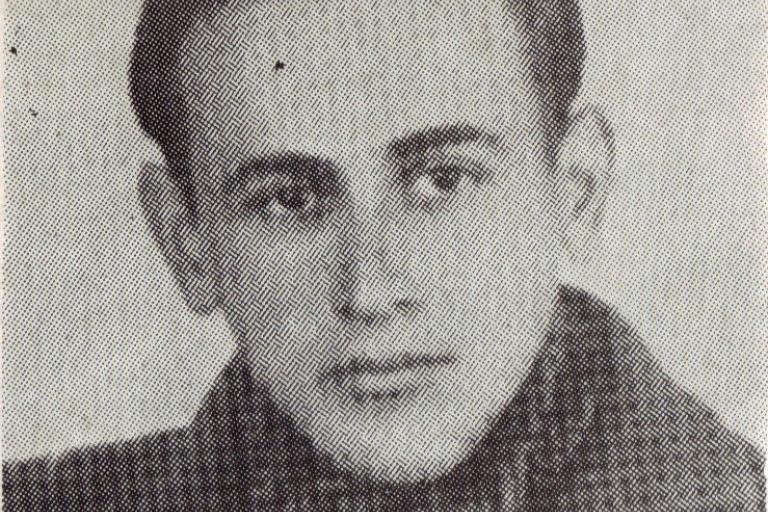

Onda is comfortable with the esoteric. Growing up in Japan, he was introduced to intellectual and avant-garde ideas from around the world. His father was a university field hockey coach, and his mother an artist. Art and literature were always around and took the place of formal schooling for him. A position as a visiting composer in the Electro-Acoustic Music Studio at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire made it possible for him to move to America. In 2003 he relocated to New York City and found Paik’s influence to be strong in the city’s fertile art scene. Through an accidental encounter, Onda even got to know Paik’s assistant and visited a storage space filled with Paik’s old television sets.

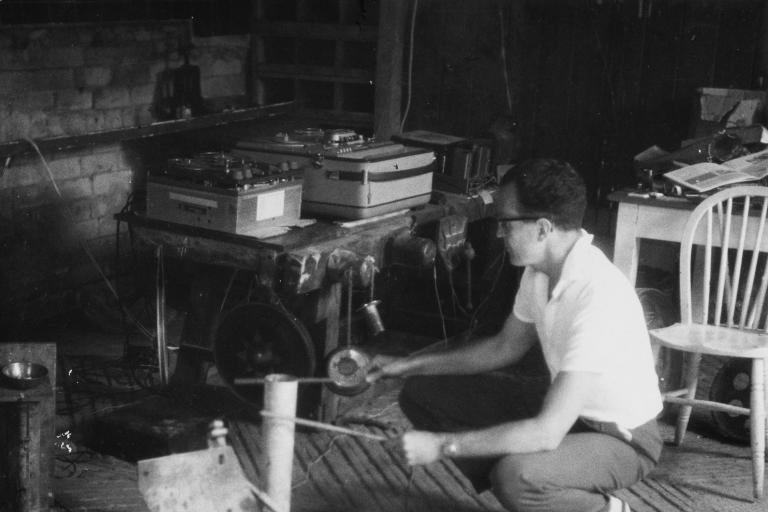

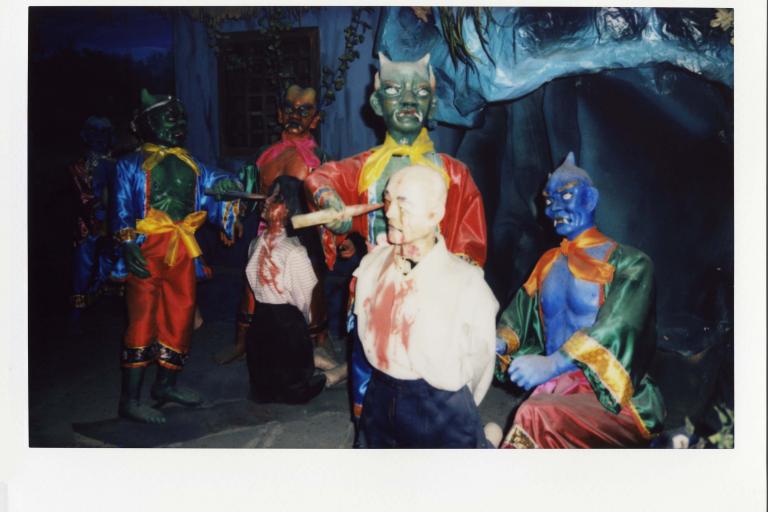

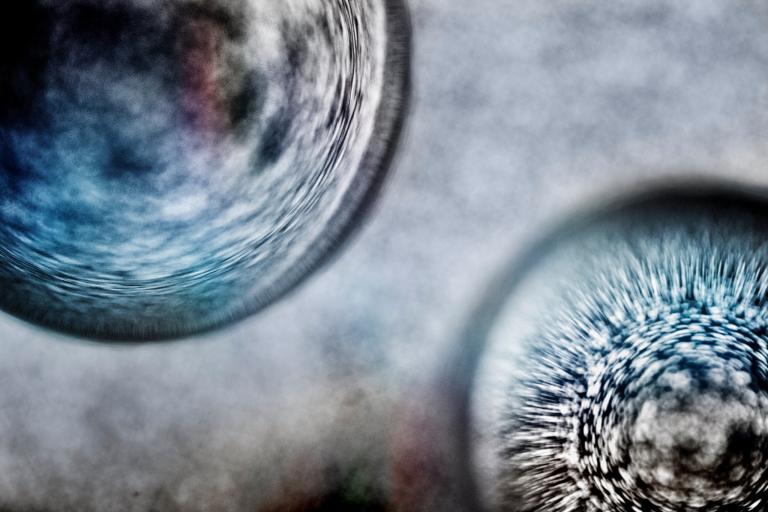

He never got the chance to meet the older artist, but in 2010 Onda was invited to do a residency at the Nam June Paik Art Center in Giheung District, Yongin City, South Korea. One night, back in his hotel in Seoul, he dialed into an unusual transmission on his radio. While he didn’t understand what the murmured voice was saying or even the origins of the sounds he was hearing, he had the feeling that a message was being sent to him.

“It was really out of the blue, but somehow I felt the sensation that Nam June Paik was speaking to me,” Onda said. “It’s hard to explain, just intuition, so I made a recording. I always carry a cassette Walkman that has a radio.”

Two years later, Onda received another radio message, this time while doing a concert in Koln, Germany — where Paik had lived while studying with the composer Karlheinz Stockhausen, as it happens. The following year, two more were received, always through radio transmissions.

Onda started talking to people who work in radio, learning about mysterious transmissions, coded messages from government broadcasts, and other unusual sounds floating through the radio waves. But nobody could decipher the recordings he’d been collecting.

He elaborated in an email after our conversation.

“I just recalled this... when I was a teenager, I got interested in the 80s NY culture through [author and radio art pioneer] Tetsuo Kogawa’s books. I do not remember if I read about Paik in his books. But those definitely helped me to absorb the new media art scene and find Paik’s art. After receiving the first message from Paik in Seoul in 2010 and immediately recognizing it as a spiritual communication with him, then more messages later, I wasn’t sure why the radio was the medium and how it worked. The first person I consulted was Tetsuo Kogawa. He explained to me there have been numerous “secret broadcasts” on anonymous radio stations around the world, and many of those continued without apparent explanation. He also tried to analyze what the transmissions I received were but couldn’t figure it out — even though he has a vast knowledge of the radio, both historically and scientifically.”

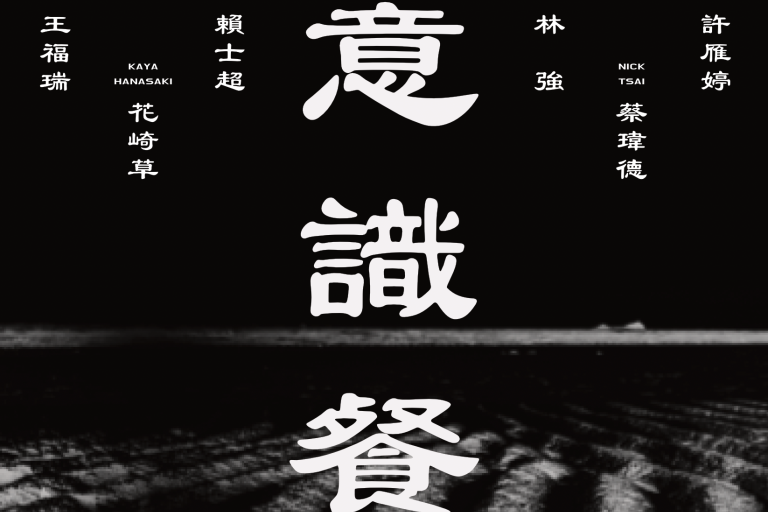

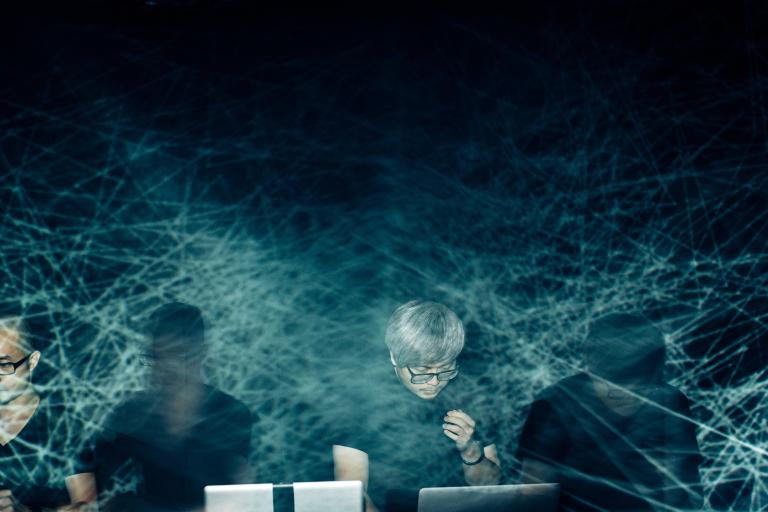

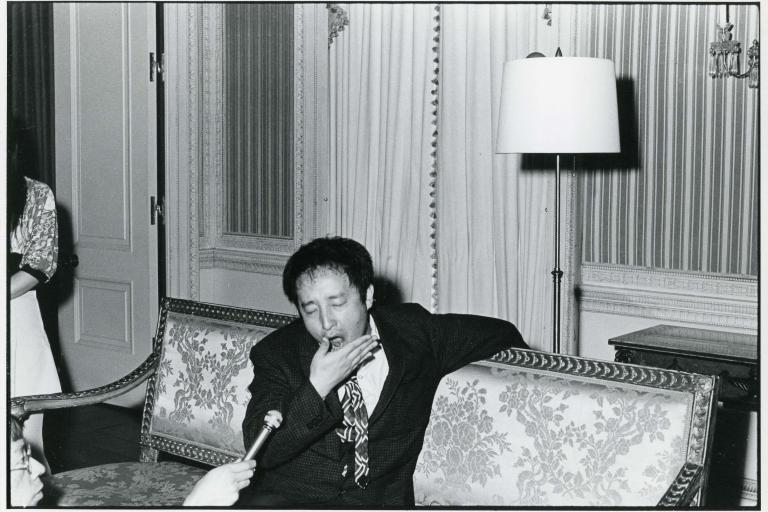

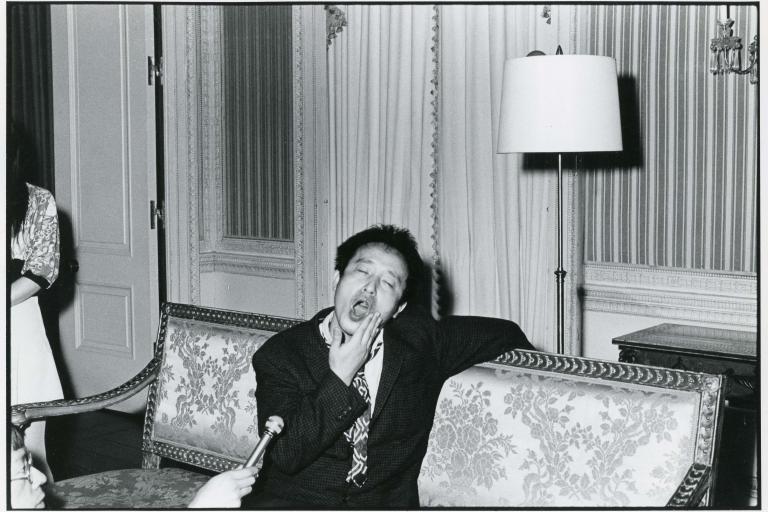

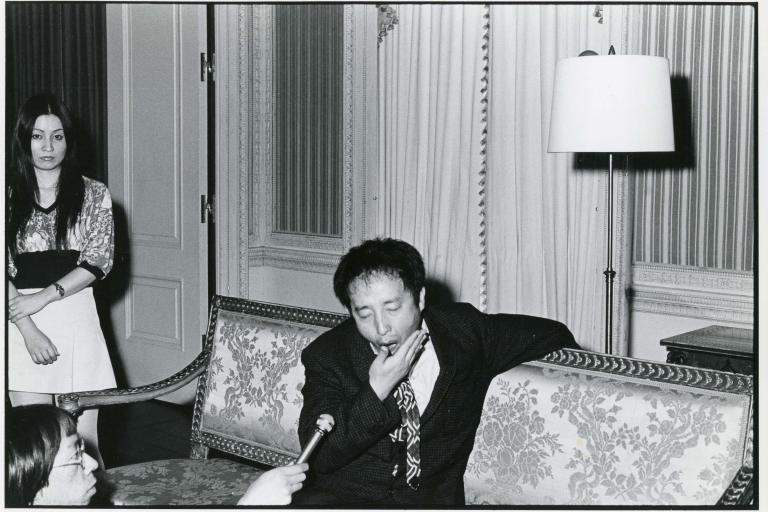

By 2013, he had received four messages but wasn’t sure what, if anything, to do with them. Then in 2016 came a commission from documenta, the longstanding German art quinquennial. He performed at the festival the following year with sound artist Akio Suzuki and edited his Paik recordings for a radio broadcast by the festival. The album Nam June’s Spirit Was Speaking to Me (released on vinyl and download by Recital records, and streaming in full on Onda’s Bandcamp) collects those messages and includes a booklet with previously unpublished photos of Paik taken on the set of Michael Snow’s film Rameau’s Nephew… in 1974.

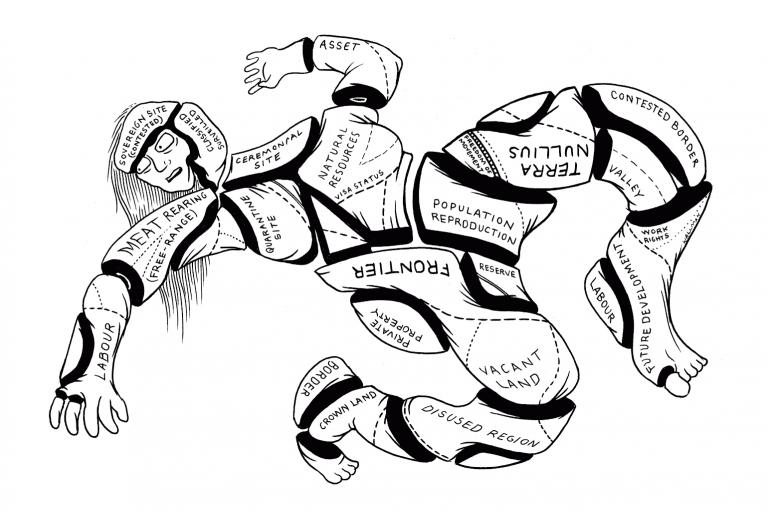

Onda’s records are generally smears of sound with flashes of cultural detritus, and this one follows suit: radio static, unintended rhythms, and disembodied voices make for an unmoored, perhaps unnerving dreamlike experience. It’s more collage than music, with seemingly unrelated sounds butting up against one another, suggesting relationships through juxtaposition. Onda’s own part in the work is a bit nebulous. He didn’t generate the sounds — he received and recorded them. His role was to frame them, to put them in context. There’s something paranormal about the work, or at least in Onda’s beliefs about how the sounds came to him. But the artist offered an explanation that gives at least a nod to science.

“It’s not something that you can say clearly,” he said. “It’s about energy. You can feel it, but it’s hard to translate into language. The energy he was creating through his TV-based work, it’s really transporting something from a long distance, sending energy. It’s traveling around the globe. For me, it was natural that I was receiving his messages from around the globe.

“It’s about energy,” he reiterated. “That contextualization is based on history and society. Hip hop has really strong energy. Why? Because it has a strong background and history. It has to contextualize in some way. If I pick up a subject such as Nam June Paik, it also connects to what he was doing and the Fluxus movement.

“I tend to find something rather than create something. It’s lots of editing. Technically, I’m like an editor — editing ideas, sounds, visuals, text.”

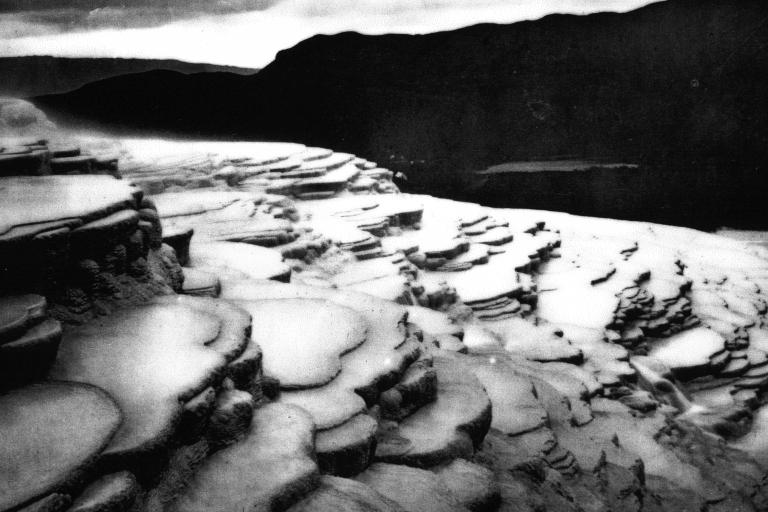

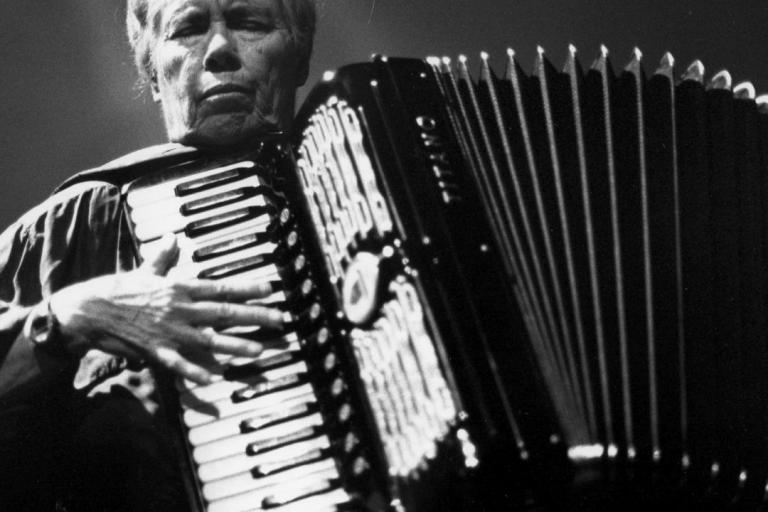

His recordings sometimes work as diaries, or sonic photo albums, although always abstract. His ongoing Cassette Memories project is derived from his own field recordings, captured — like the Nam June Paik messages — on a handheld cassette recorder, which he layers and electronically alters in real-time. The effort exists as a sort of performative installation and also on record. The first three volumes of Cassette Memories — comprised of recordings made in New York, New Hampshire, Mexico, Rio de Janeiro, Salvador, Tokyo, Paris, Tangier, Valencia, Lisbon, and London — were reissued digitally by Room40 and can be streamed in full online.

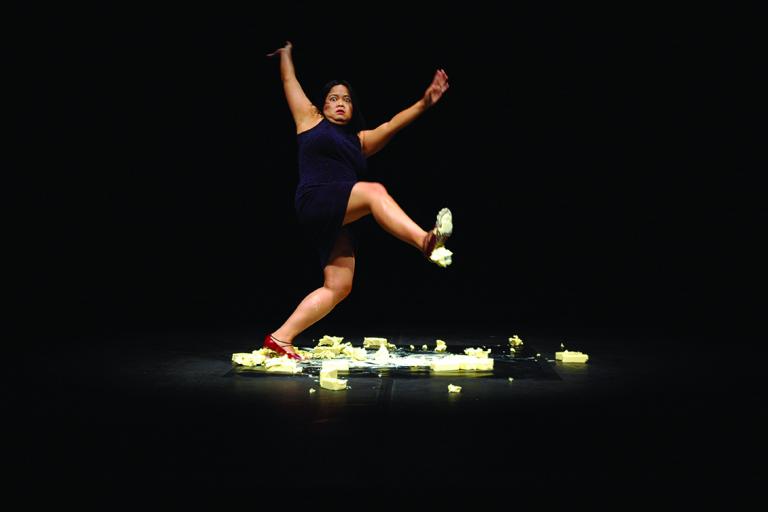

Rupture, released in August 2020 (and the first of three records he’s releasing before the end of the year), pairs his field recordings and cassette manipulations with reeds, mandolin, and percussion in a four-part suite inspired by Italian folk music and legends about the deadly tarantula spider, originally scored for the SU-EN Butoh Company. That will be followed by recordings with Akio Suzuki and another sound artist, Nao Nishihara.

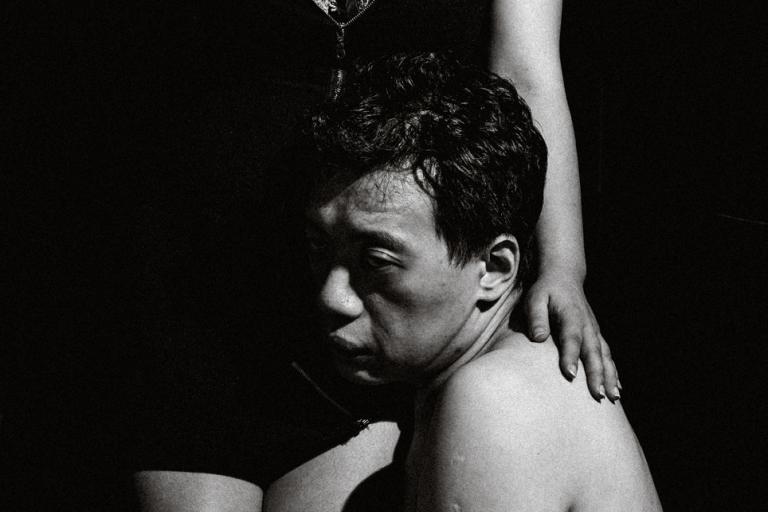

Collaboration is a big part of Onda’s work — but it, too, takes different forms. His long friendship with the New York minimalist guitarist Loren Connors has led to a different sort of collaboration, one of photographer and subject. In 2019, Onda uncovered about 100 roles of unprocessed films he had shot more than a decade earlier. When the Brooklyn venue ISSUE Project Room approached him to do a piece for its Isolated Field Recordings video series during the coronavirus lockdown, Onda paired the photos with recordings of Connors’ music for a video portrait he titled “Captured in the Air”.

Here again, Onda’s work is that of framing another artist. It was the final installment of ISSUE’s series, and it frames Onda’s own time in New York. The first concert he saw of Connors was his collaboration with the late poet Steve Dalachinsky at the Knitting Factory in the late 90s.

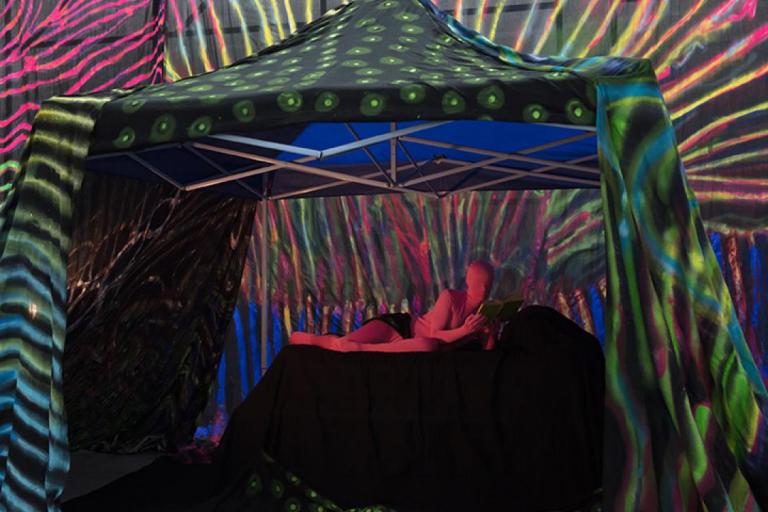

The move to Japan is temporary. Onda and his wife, the artist, and photographer Maki Kaoru, were preparing to move to Brussels when the pandemic struck. While he’s there, he’ll have an installation piece at Arts Maebashi in Maebashi City in an exhibition, Listening: Resonant Worlds, curated by the museum’s Director Fumihiko Sumitomo.

At least for a little while, it is something of a return home for the two (Kaoru is originally from Mito). But even the notion of ‘home’ isn’t simple for Onda. His paternal grandparents moved to Japan from the Southern part of Korea during World War II. As a young field hockey star, Onda’s father was able to gain Japanese citizenship so that he could play on the Japanese team in the 1964 Olympics in Tokyo, adopting his wife’s family name, Onda, to replace his Korean surname. A technicality prevented his father from participating, but he competed in the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City and then coached and managed the team. His mother was born in Japan, the niece of Kazuko Onda, a journalist, and early suffragist. “People thought she was too eccentric in the conservative Japanese society,” he wrote in another follow-up email shortly after arriving in Japan.

“She was a diva-type, and everybody had such a hard time with her. But she deeply loved me, and I only have fond memories of her. She and my father taught me that it’s okay to be my own self and ignore the social norms. My sexuality was ambiguous when I was a child. I wanted to be a girl (I changed my name to Aki, which is a female name in Japan), and I loved wearing girls’ clothes. People thought I was crazy, but I had the strength to fight against their projections. Eventually, I stopped going to school and skipped formal education.”

While he grew up in Japan, Onda doesn’t consider himself to be strictly Japanese.

“I was born in Japan and grew up there but have never identified myself as a Japanese nor Korean, though I’m proud to be Asian. Moreover, as my family extensively traveled around the world, it was easier and more convenient to consider ourselves as ‘nomads’.

“Maybe that echoes with Paik’s life. He was born in Korea, but his family had to flee from Seoul during the Korean War. (Korean people hated this, and for decades, Paik’s family had a negative reputation in his country.) Then he studied in Japan and Germany before he settled down in New York. As Yuji Agematsu, a New York-based visual artist testified in an interview. In some fundamental way, he was a nomad from continental Asia, and there was no need for him to stick to just one language (or country).

“This not-belonging-to-anywhere or nomadic nature reflects my art practice and Paik’s — different artistic forms are combined and collaged in a complex way, and something very unusual or hard-to-define reveals itself during the process. I think this album Nam June’s Spirit Was Speaking to Me explains this well.”

This, perhaps, is how to frame Onda’s art, or at least how he sees it: unidentifiable recordings of unknown origin attributed to another artist, one who died 15 years ago. Onda is serious about his work but remarkably humble. Compliments are met, again, with laughter. He has a particular way of owning his work without taking credit for it. It’s that thing that’s “hard to explain with language,” which “comes from somewhere else,” that’s “something spiritual,” which he doesn’t want to mystify, as mystical as it is. What makes the radio signals into messages from Paik is, perhaps, the belief that that’s what they are, the faith in something outside himself floating through the air.

“Spiritualism, what happens after you die — something remains,” he said during the call. “Some people believe that’s the pure end, but I believe something goes on.”