The major wave of Asian biennials began around 25 years ago, with prominent new biennials initiated in Gwangju (1995), Shanghai (1996), and Taipei (1998). Other biennials and triennials followed in Busan, Singapore, Guangzhou, Yokohama, Yogyakarta, and other cities, not to mention biennials like Sydney, which reconfigured themselves to fit the new globalized biennial model: a collection of international artists, a (usually foreign, famous) independent curator, and a highly theoretical statement by way of a theme.

By the early 2000s, the art press was raising the alarm at a new wave of “biennialization”, which saw biennials popping up around the globe like McDonald’s franchises. Paradoxically, most of them seemed to denounce globalization, of which they were a perfect example. It was also feared that this proliferation of biennials threatened to kill the radical and properly avant-gardist potential of theoretical discourse by institutionalizing it as fast as it could be produced.

But in regards to the production of any sort of non-Western paradigm, there are at least two main problems. First, it is obvious to say that the region is incredibly diverse, but perhaps more crucial and in stark contrast to the West, Asia is still simmering with territorial conflicts and resentment over historical wrongs. China, India, Taiwan, Japan, the Philippines, Vietnam, and of course, the two Koreas are still fighting over land and seafaring rights within the region. In many regards, World War II and the various wars of the 1950s (the Korean War, Taiwan-China, China-India) are still unresolved. Second, the theoretical toolkit for discussing contemporary art still comes from the West, more generally the ideas of critical thinkers based in France, Germany, the UK, and the US. One cannot underestimate the gap separating Western-global theory’s concerns from the populations these new biennials are trying to serve.

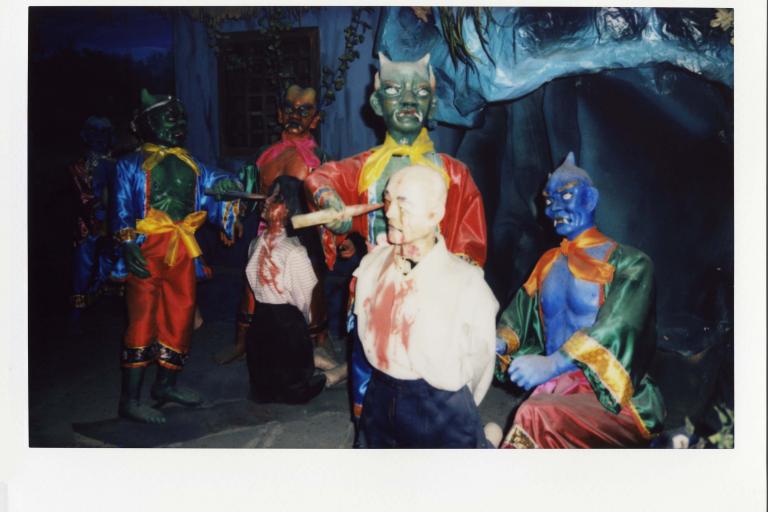

A poignant example of a theoretical disconnect was the 2008 Taipei Biennial, curated by Manray Hsu and Vasif Kortun, which set out specifically to address “a constellation of related issues arising from neo-liberal capitalist globalization”. The biennial itself was basically a protest movement under the thin disguise of an exhibition of contemporary art. And yet, what no one could predict was that during the biennial’s opening weekend, violent protests occurred literally right in front of the museum, with Taiwanese citizens in bloody clashes with police on the major Taipei thoroughfare of Zhongshan North Road.

What’s more, these protests had nothing to do with the exhibition’s radical anti-globalist works and statements. The Taiwanese were instead protesting the arrival of a Chinese government envoy and their own government’s capitulation to Chinese demands, such as not flying Taiwan’s national flag within sight of the Chinese official’s automobile route. The Taiwanese feared the loss of sovereignty and democracy.

The foreign artists, many of whom were also activists who had participated in anti-globalization protests from London to Buenos Aires, were taken aback by the disconnect. They had incorrectly assumed some sort of global common ground could exist in movements for resisting global capitalism, but they found that despite the presumed connections of a supremely networked world, every local movement has its own particular issues at heart. And the connections are not obvious. How should Taiwan’s movement for self-determination (or Hong Kong’s?) fit into the protest movements of continental Europe or the UK (themselves now starting to splinter)?

But after a quarter-century of Asian biennialization, some shared notions must certainly have begun to take shape? Empirically speaking, I would argue that institutional models have solidified, and the community of an Asian contemporary art crowd has emerged. Art professionals and administrators have now made careers working on biennials, interfacing on the one hand with the local public and on the other with international networks. Attending the various biennials of East and Southeast Asia, one sees the same faces everywhere: curators, artists, academics, government officials, gallerists, collectors, art-world media, and so on. A sort of jet-setting Asian art crowd has emerged. They are an internationalist mix: from every nation in Asia and also include ex-pats and partisan Western critics. English is their lingua franca.

This does not quite make for a paradigm, but it has the beginnings of one. The inclinations to discover common ground continue to surface, and attempts to explore regional commonalities become stronger and more confident.

One of the more ambitious attempts thus far was the 2017 exhibition Sunshower: Contemporary Art from Southeast Asia 1980s to Now, held at Tokyo’s Mori Art Museum. The museum is fast asserting itself as one of the only true leaders in regional art trends. In fact, it is one of the only Asian museums willing to step into the role of a regional leader (as opposed to merely serving a local public). Art institutions in most Asian nations are generally tasked with two functions: nation-building by defining a national art history or hosting touring Western exhibitions to validate their own national art history by tying it to that of the West.

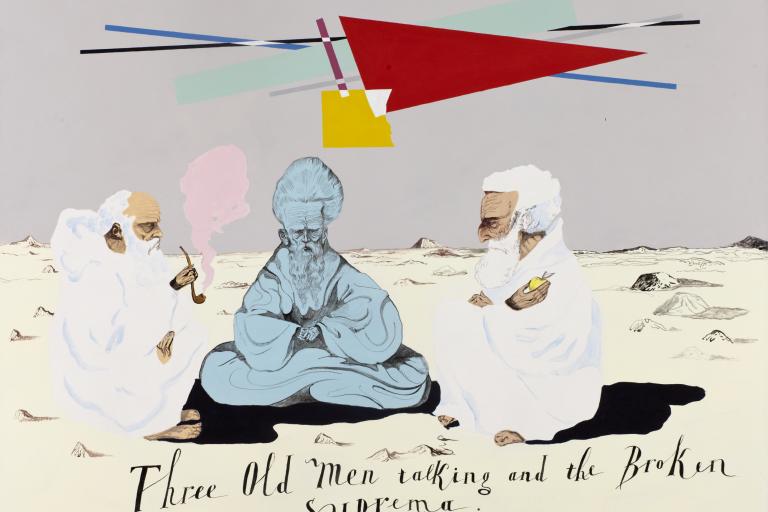

This is not to say that Sunshower was a total success. The exhibition introduced itself with a kind of disclaimer, stating that “multi-ethnic, multi-lingual, multi-faith Southeast Asia has nurtured a truly dynamic and diverse culture”, albeit one that the artworks selected for exhibition could not quite manage to bring into cohesion. But one could start to discern common threads. Within Southwest Asia, there is a shared sense of the need for local cultural renaissance, the need to re-assert native cultural elements within the scope of a homogenized, globalized sameness. Also, there is a desire to lay bare dark histories, historical wrongs, and current injustice to effect reconciliations so that societies can move forward. These movements are by and large confined to national borders, but at least within the art world, there is a growing sense of mutual appreciation and understanding.

So while it may still be impossible for the various peoples of Asia to agree on any sort of overarching narrative, what may be more promising, and also more organic and less programmatic, is the formation of regional networks of artists, curators, and critics — i.e., the biennial jet set. They now routinely find chances to invite each other to panel discussions in regional museums, group exhibitions, and other events outside of the tent-pole biennials. There are more chances for exchange than ever, and the amount of inter-Asian dialogue is growing.

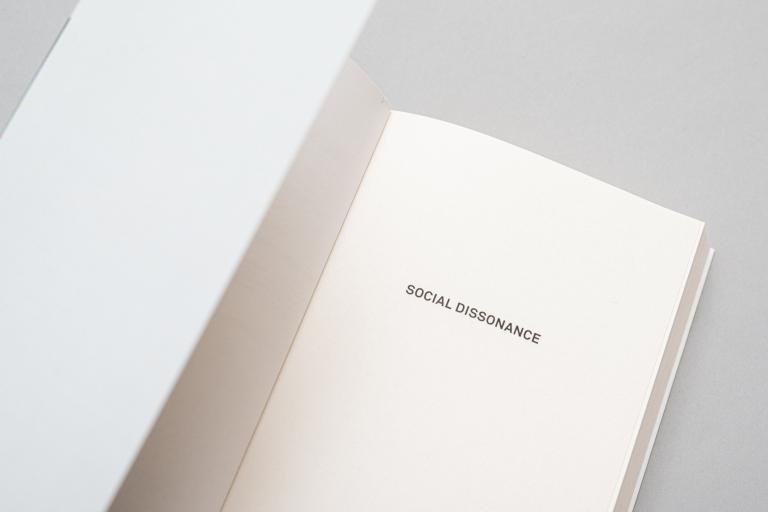

One new node in this network is Curatography*, an online journal launched from Taiwan in May 2020. Published in Chinese and English, it is “dedicated to the exploration of contemporary art and curatorial culture”, specifically “the geopolitical dimensions of cultural production in East and Southeast Asia.” In addition to its Taiwanese editorial board of Hongjohn Lin, Manray Hsu, Sandy Lo, and Yi-wen Chang, for its first two issues, it invited articles from Eileen Legaspi Ramirez (Philippines), Yoann Gourmel (curator at Palais de Tokyo in Paris), Raqs Media Collective (India), Ruangrupa (Indonesia), and Pawit Mahasarinand (Bangkok Art and Culture Center, Thailand).

Curatography, a neologism that could be defined as “the mapping or writing of curation”, launched with the fairly basic notion of bringing Asia-region curators and artists together to share their individual experiences. But this was also underpinned by a theoretical position that referenced Boris Groys’ idea of the “cultural archive” and Jacques Rancieres’ concept of “the political”. The general implication here is that history (and historical truth) is always contingent; one should shy away from universal value; and if we are to follow Groys, instead of authenticity, we have “the fiction of stabilities through time”.

The preoccupation now is that in judgments of value (artistic or monetary), a sort of primacy is given to politics (one could also say, historical outcomes) over and above any innate qualities of the works themselves. (Who now talks of aesthetics? Or beauty?) For example, Curatography’s first issue included the article “Les fleures américaines” by Yoann Gourmel and Elodie Royer, describing an exhibition of the same name held in Paris in 2012. In it, we are given a political history of modern art, that Picasso and Matisse, for example, were collected avidly by Gertrude Stein and her brothers (in 1900–1910s Paris), and this collection greatly influenced the initial collection of MoMA New York (established in 1929), which in turn served as the basis for the writing of what is now considered the definitive history of Modern Art. Gourmel and Royer do not push their point further, but one can easily infer that such a view of cultural value as conferred by a political outcome can be grounds to challenge larger historical narratives, such as the pre-eminence of Western art in the narrative of World Art.

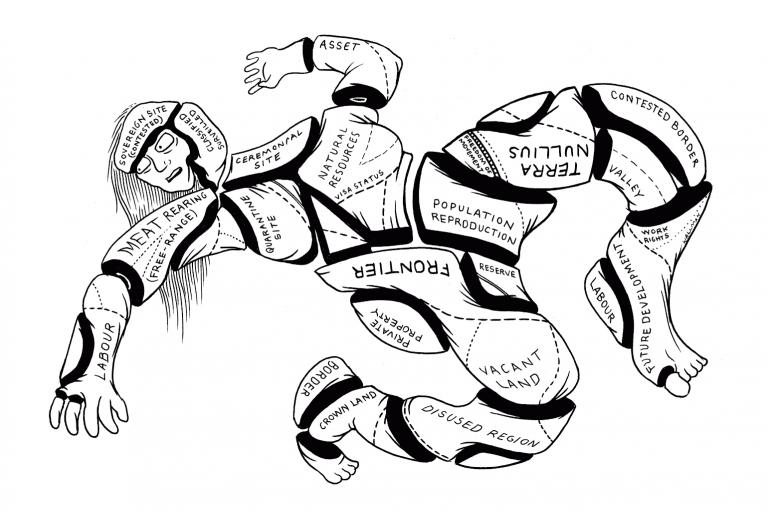

In another article, “There are No Blank Slates”, Filipina scholar Eileen Legaspi Ramirez laments the historical burdens still saddling Asian nations and how the stereotyping of Asian art movements diminishes more fundamental problems of authoritarian regimes and human rights: “like most postcolonial sites, Asia continues to be associated with tropes of emergence, particularly in regards to contemporary art.” She goes on to call out “art history for being generally oblivious to local nuance”.

How can the concerns of contemporary art in Duterte’s Philippines –– poverty, police death squads, a massively confusing colonial history, the export of its population as a primary means of national income –– become meaningful in Japan or Korea, or Vietnam? It is an extremely difficult question. As I noted at the beginning, there is still no such thing as an Asian paradigm. And perhaps there never will be any need for such a universal project. But one can be greatly encouraged by the growth of inter-Asian dialogue, networks, and even friendships. At the very least, we in the region are all learning how to talk to each other.

* David Frazier has done freelance editing work for Curatography.