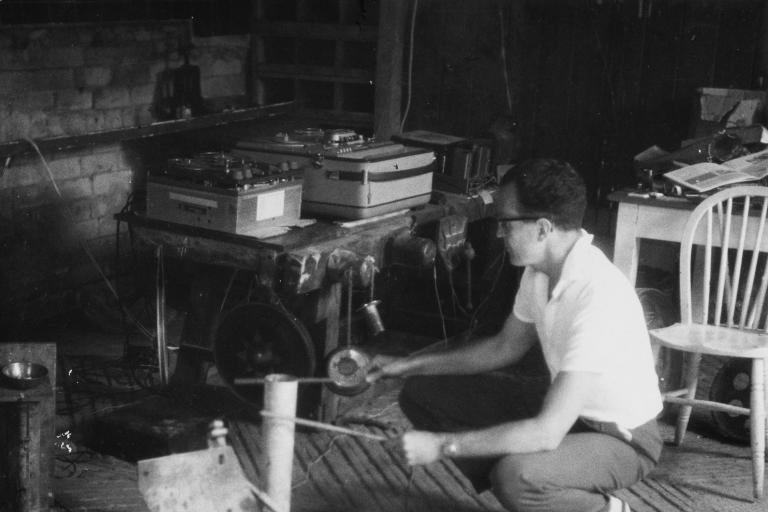

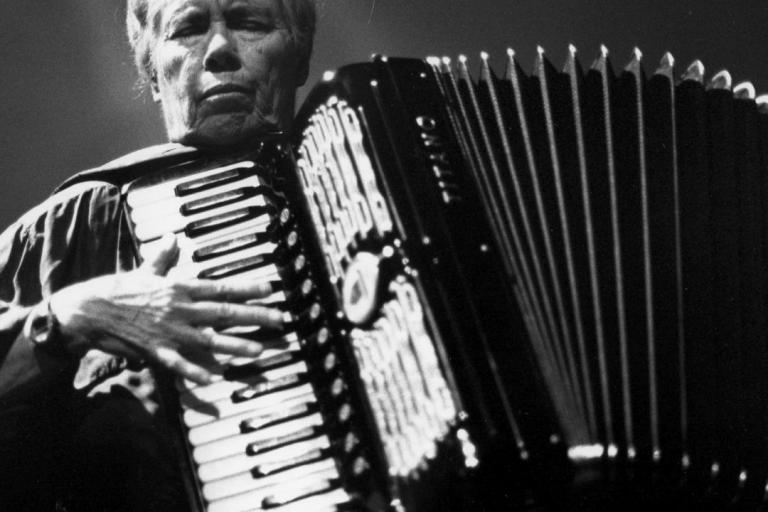

While growing up in Buenos Aires, Anla Courtis studied music composition at the Conservatorio Municipal Manual de Falla before co-founding The Burt Reynolds Ensemble (later re-named Reynolds) in his early twenties. Since his first solo release as Anla Courtis in 1996 (Poliestireno Expandido on the UK label Matching Head), he has made a name for himself as one of the most prolific musicians of South America, with a catalog of over 140 releases on different labels around the globe. He has collaborated with many other experimental musicians, including Pauline Oliveros, Kawabata Makoto (Acid Mothers Temple) and Rokugenkin, KK Null, Campbell Kneale, Tetuzi Akiyama, Merzbow, Aaron Moore, Detlev Hjuler and Mama Bär, Lasse Marhaug (Jazzkrammer), Pablo Reche, Anthony Milton, Tomutonttu, and PBK. Courtis specializes in guitar improvisation, cassette tape manipulations, and experiments with a menagerie of modified instruments. In 2017, Courtis released Los Galpones on Fabrica Records. The album contains four dark and grimacing industrial-tinged drone pieces reflecting upon the post-industrial landscape of the artist's native Buenos Aires.

Thomas Bey William Bailey: Shall we begin by discussing what you're up to right now — for example, this new LP — since it relates very much to the main topic of our interview? The brief description that the label provides for the album mentions something about the decaying post-industrial landscapes of Buenos Aires. Is that a true statement — is the local environment really dominated by this type of decay? And has it had much of an impact on your creativity and expression?

Anla Courtis: Well, the title Los Galpones can be translated as "The Sheds" (or maybe "The Storehouses"), and it refers to that kind of old big zinc shed with some abandoned quality that you can find mostly outside the city. I live right in Buenos Aires downtown, so not many of those sheds are there, but occasionally you can still find some in non-central city parts, and there are plenty of those in the surroundings, especially in the rural areas. In any case, the idea came from the sound: I was getting guitar sounds with, let's say, some isolated character, and I thought instead of garage rock, this was sounding more like shed rock! So I decided to do a whole record with that kind of sound.

TB: As far as the galpón you mention, do you have any personal connection to them that you wanted to explore, in addition to what you mentioned about the unique acoustics of the spaces? I mean, is there any sentimental connection that you have to these spaces or any larger cultural memory associated with them?

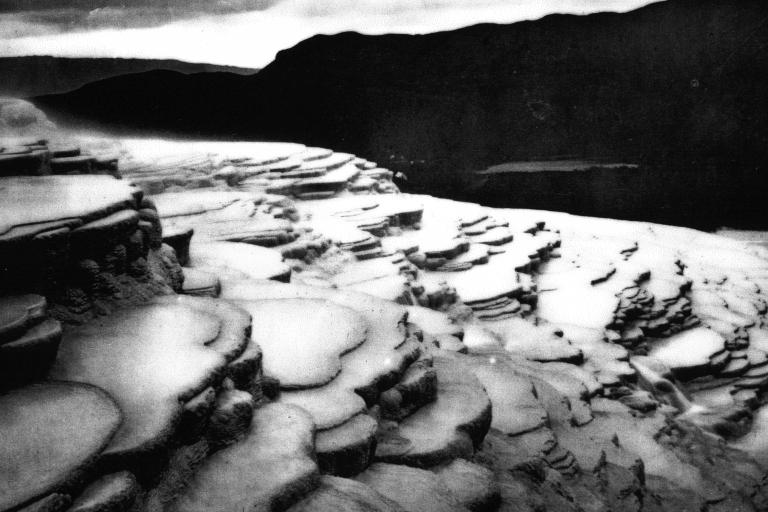

AC: Of course, there's some amount of cultural memory associated with them. For instance, when I was a kid, I played in my uncle's galpón, which was full of metals. And then I've seen many of these galpón all around the country, mostly in the rural parts of Buenos Aires province but also in Patagonia (in the very south of Argentina) where I visited some huge old sheds for sheep shearing. In any case, the sound of the record was not actually recorded in a proper galpón, but it was the imaginary reference that, in the end, helped me to create a sounding landscape for the whole record.

TB: I am definitely interested in how our built environments are not merely passive but active participants who provide us with feedback on the sounds that we initially transmit (these can be isolated structures like the sheds you mention or entire cities). Can you think of any other unique architectural features of Buenos Aires (or Argentina as a whole) that you have entered into a kind of dialogue with — buildings or locations that helped shape your sound in ways that you had previously not expected?

AC: I agree, environments are not just passive — somehow, they affect us. There's a certain type of let's say, psychogeography related to specific spaces that, of course, can be reinforced by the music in a more specific or incidental way. Actually, there's a kind of paradox because the sound is at the same time very physical and very unphysical. The physical aspect is relatable to how the sound is reflected in some specific spaces. The unphysical aspect comes because sound lasts only a second, and it's gone, so it works on the imaginary side from then. In any case, yes, I have some specific sound memories of Argentine locations, to mention a few: some underground venues from the 80s, old flats, and basements, and things like the sound of the wind in deserted Patagonia or the infinite noise of the Iguazú waterfalls.

TB: This makes me think a little about the increasing virtualization of space, using GPS technology and (soon) 'augmented reality' tools in which you will be bombarded with others' opinions and impressions of space before you have had the chance to draw your own opinions about that space. For example, imagine you are traveling to the waterfalls you mention and your 'Google Glasses' advise you that the waterfall has only a two-star rating overall from visitors, that many tourists have claimed it to be too noisy or something... with this kind of future ahead, I feel like the entire nature of why we record on location will change. Meaning, it will become an act of resistance against having your decisions made for you and will be a deliberate attempt to communicate with an environment on a personal level without caring what the existing consensus is. Do you agree?

AC: Well, I'm not sure how it will be traveling in the future, but for sure, there's some tendency which is not entirely new but probably increased with technology. It's this tendency of getting it all done for you, think of package tour as a kind of fast-food-tourism: of course, then you'll go there, but I wouldn't say you'd really be able to know the place that way. In music, there's something similar, for instance, with keyboards — or sound processors - and the idea of preset. I mean, some of them can be useful, but if you only play with presets and don't try to find your own sounds, then the comfort zone can easily turn into a trap. For example, on some tracks of Los Galpones, I worked some rhythmic stuff but tried not to be confined to the standard side. Nowadays, setting a rhythm with a computer is the easiest thing on earth, but sometimes it turns into something meaningless. So I was working on tracks where the rhythm part is somehow out of focus and is mutated by slight tempo changes, but there's still some beat there if you listen carefully.

TB: Your comments in the last answer make me think about all the different rebellions against the preset culture that have happened or are still in progress. For example, circuit-bending is an ongoing culture that aims to radically different (and much more unpredictable) sonic experience from very standard equipment. Or there is the increased interest in just building all instruments from scratch, whether by handcrafting or by creating new computer algorithms. Have any of these been especially useful to your personal expression? And also, do you notice any of those techniques becoming more popular within Argentina?

AC: I'd say there are many ways to try to escape the preset, but we need to be careful: anything can sooner or later turn into a preset. About circuit bending, yes, there's some small scene in Argentina with people doing workshops and using this stuff to play with. In general, I think it is interesting, but sometimes I also think the music coming from these hacked circuits sounds pretty similar. I think there's some potential, but it probably needs some research to find more options and alternative ways of using them. I've tried it myself a little bit and, although I wouldn't use it as my only sound source, I've definitely had fun. However, beyond technology, I think we need to be alert all the time in all directions to escape the preset zones.

TB: Keeping in mind the idea of preset culture, I have noticed one of the main distinguishing features of this so-called sound art culture is that the artists involved (or at least the ones that I'm interested in) genuinely want to change their own perceptions in addition to the perception of their audiences. They seem to be questioning their own cultural or perceptual presets before they present work to an audience, and in that sense, the music is truly experimental. What do you think — are we, as a global subculture, moving more in this truly experimental direction, or are we still, for the most part, stuck in a situation where both the majority of musicians and the public think 'experimental' is no more than something that sounds weird?

AC: It's difficult to give a global answer. I think there are many contradictory realities going on at the same time. Its true technology is giving us some new possibilities for the expansion of freedoms, but at the same time, it's generating more presets and a lot more control. So it's a complex situation, a bit paradoxical on many levels. It's an ethical decision to preserve the more experimental instances in such a context.

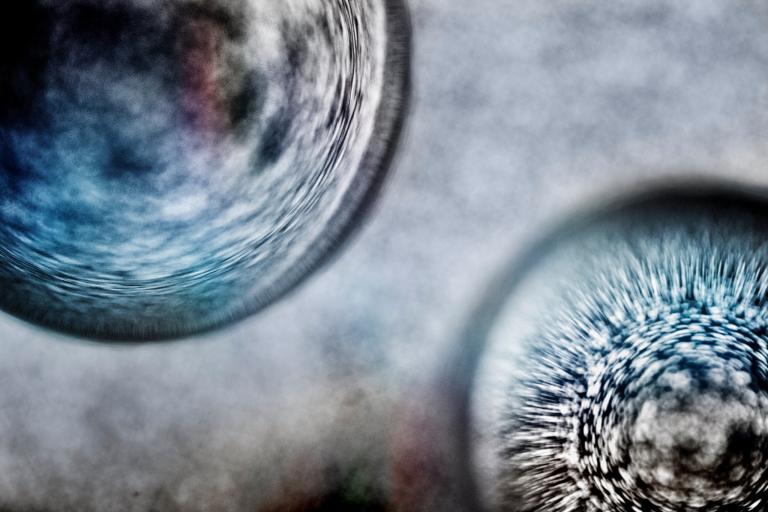

TB: Another intriguing release you sent me recently was the Coils on Malbec LP with Cyrus Pireh. This recording features the sound of electrical coils being placed over small bowls of Argentinian Malbec wine. This fascinated me since it distills an element of Argentine culture into a sound experience that you wouldn't expect. It goes beyond simply representing a local environment with field recording, giving a voice to something supposedly non-communicative. I'm very interested in these kinds of efforts. Can you think of any similar recordings from yourself or others that attempt to accomplish the same thing?

AC: Coils on Malbec somehow tried to voice Malbec, the most emblematic wine — and grape variety — from Argentina. Since we recorded it in Buenos Aires with Cyrus, it made sense for us to use such sources. In this case, the Malbec wine had coils, so they were not liquid sounds recorded by regular microphones but electromagnetic variations on wine captured by coils. And I have some other projects exploring different areas. For instance, I could mention that record I made with an unstrung guitar found at a second-hand store without a bridge. In this case, of course, it's a different approach, but in a way, it was also giving a voice to an instrument that would have been normally discarded.

TB: I think one of the most interesting aspects of the process we're talking about (giving a voice to otherwise unheard objects, spaces, etc.) is the process of choosing what kinds of things to amplify in the first place since there's a universe of different possibilities. It seems like the things we have discussed so far have a strong personal resonance for you — when you work with them, is your intention to make a kind of audio auto-biography, or maybe to do something completely different from this?

AC: There's indeed some resonance with all these objects, spaces, etc., but also there's some mystery as to how they all work. The same thing happens with the autobiographical aspects; they are obviously there, even if you don't want them. However, in my case, I don't necessarily want to be pinned to the autobiographical thing. I think it is always better to keep meanings open so the audience can fill them with their own histories. In that sense, each person will experience the sound according to its own resonance.

TB: I do agree it's important for people to make their own individualized interpretations of a piece, even if that piece comes with autobiographical information, as you say. Has anyone in your audience communicated any interpretations or reactions that you found particularly surprising or interesting? Have any reactions to your work been strong enough that they changed your approach to making art?

AC: It's not just an intellectual interpretation. The whole way a piece is perceived can radically change from one person to another. Over the years, I've learned to listen to what people say but at the same time try to keep it somehow open, because many times I received feedback about a piece saying one thing, and later somebody else said exactly the opposite! It happens! And in a way, it is fascinating because meanings can change or evolve even in the same person, so something in the music seems to be alive there. And to realize this has, of course, affected me.

TB: I think with music like yours radically open to interpretation, critics will often claim this is the case because there's nothing truly distinct or unique about the music. Yet your works do stand out when I listen to them, even if I can't perfectly verbalize why. Is there a factor, or are there factors that separate what you do from the many other examples of free and experimental sound?

AC: Firstly, things not easy to verbalize are systematically rejected by some critics for obvious reasons, but in fact, those kinds of things are usually quite important. However, I'm definitely not the best person to talk about my own work's unverbalizable aspects. The only thing I can say is: behind any technical or esthetical procedures, there's always some search, and if that search goes deep enough, no matter in which direction, then you'll definitely notice something when listening to the music.