The history of electronic music in New Zealand — as it relates to work that does more than merely duplicate what is done in other countries — is dominated by improvisation.

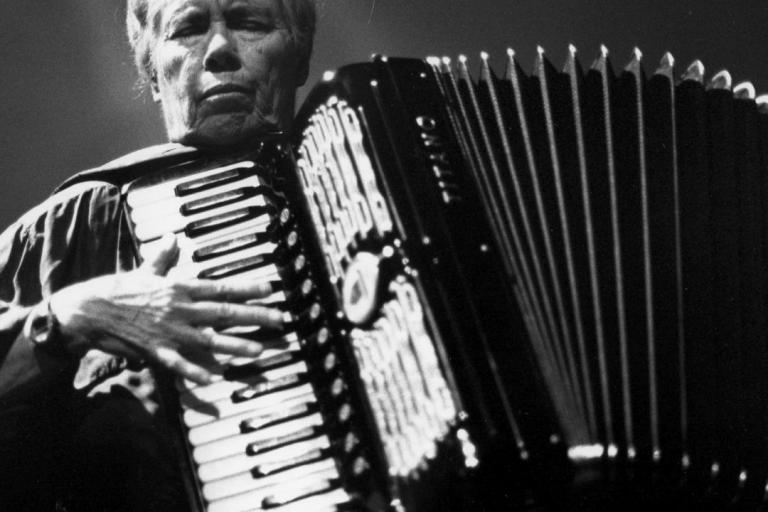

The first New Zealander to enter this realm of aural freedom was — improbably enough — an established orchestral composer and academic called Douglas Lilburn. He was seeking a way to make music that aurally evoked New Zealand, and had realized that European orchestral instruments were “pre-loaded” with such a wealth of cultural references that they struggled to relate to a new country. “New” in the sense that the entirety of human settlement here is no older than the history of polyphony in European music.

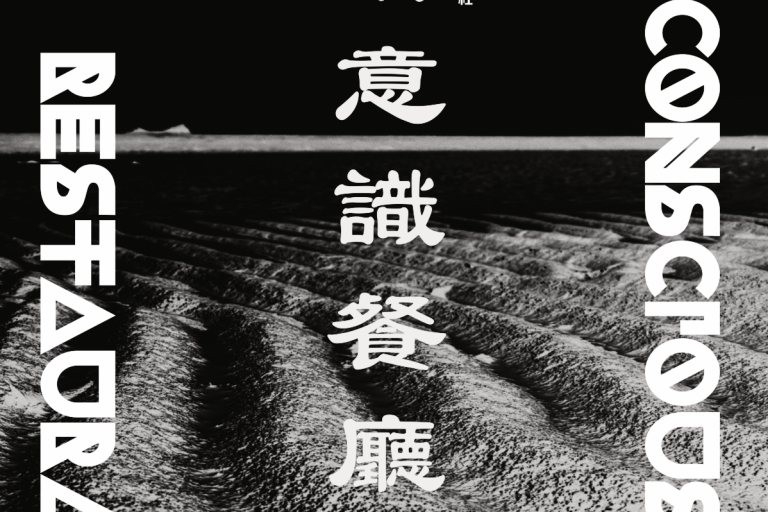

In 1963, Lilburn traveled to North America and the UK to investigate recent developments in electronic music, returning determined to exploit these new methods to create a truly “Antipodean” sound. But of course, despite having seen the RCA Synthesiser II at the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center in New York, what Lilburn did not have was any actual equipment capable of electronic sound synthesis.

Turning to the only local technical resources available, he spent the next two years working with a pair of dedicated radio technicians — Wallace Ryrie and Willi Gailer — improvising studio resources out of nothing. As a result, the first piece of electronic sound fully recorded in New Zealand, “The Return” (1965), relied on very limited technical means — manipulated studio and field recordings, white noise, and standard broadcast filters — to produce a fully realized soundworld.

Reading Lilburn’s descriptions of these early efforts, what strikes me is that Herculean efforts of imagination were devoted to working out how to radically misuse audio equipment to realize his compositional ideas (Lilburn and Harris, 2004).

Naturally, as “proper” resources could be gotten hold of, this technical improvisation faded from the work of what became known as the VUW/EMS at Victoria University in Wellington. And gradually (thanks to intolerance within the New Zealand classical music market), the work of this studio became more and more introverted and addressed increasingly to listeners within the conservatorium itself. Throughout the 1970s, such experimentalism, as existed, gradually lost touch with broader audiences, including those who were accustomed to electronic sonorities within the context of popular music.

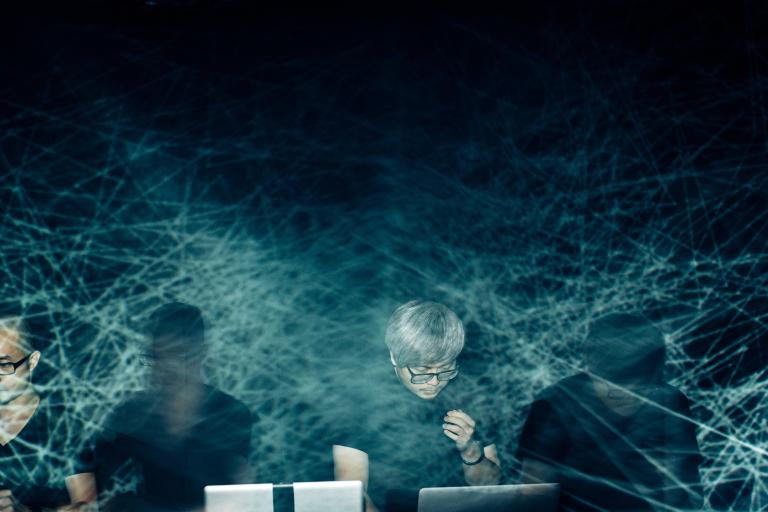

But what interests me is the way that, despite such an unpromising start, technical improvisation spread through New Zealand like a virus from this first appearance within the conservatory. It has subsequently become pretty much the defining feature of indigenous sound work here, and I have attempted to denote this through the use of the term “mis-competence”. This I have defined as “the ability to do something both deliberately wrongly, and well” (Russell, 2010, p.105).

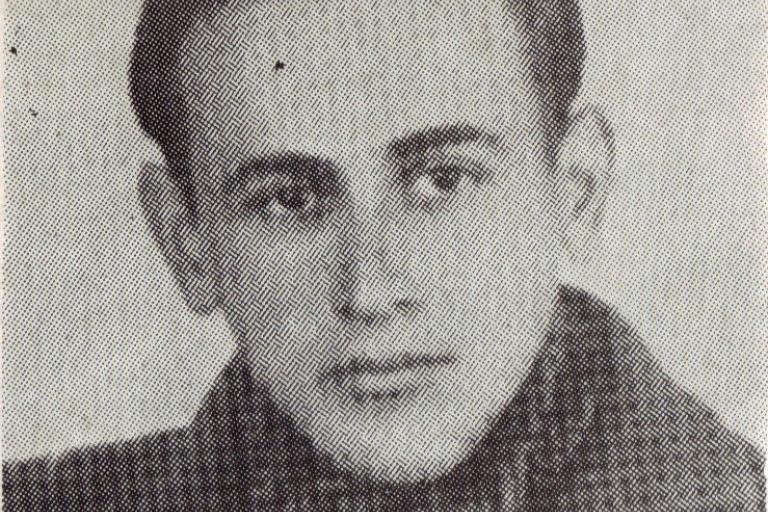

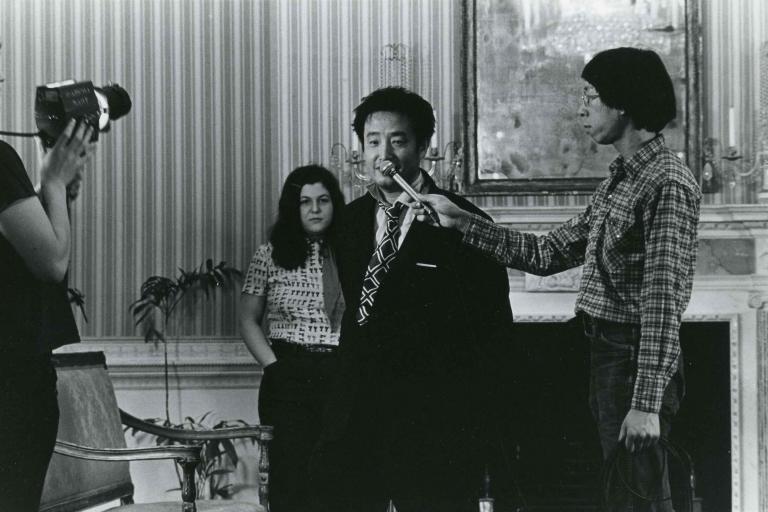

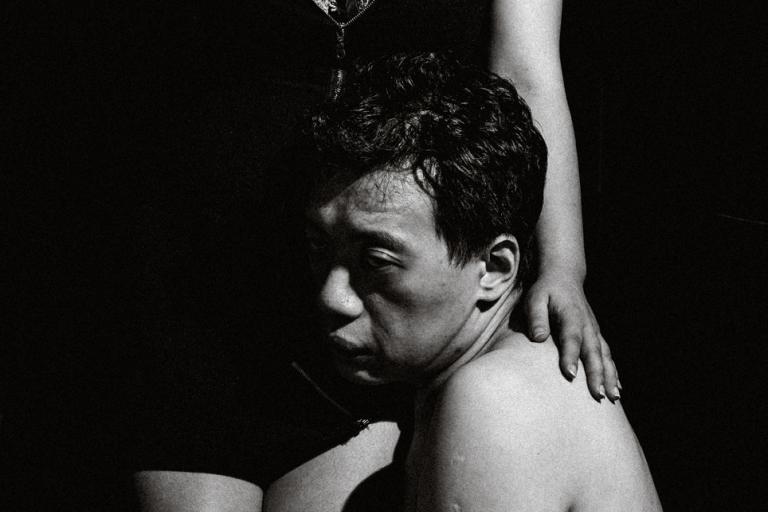

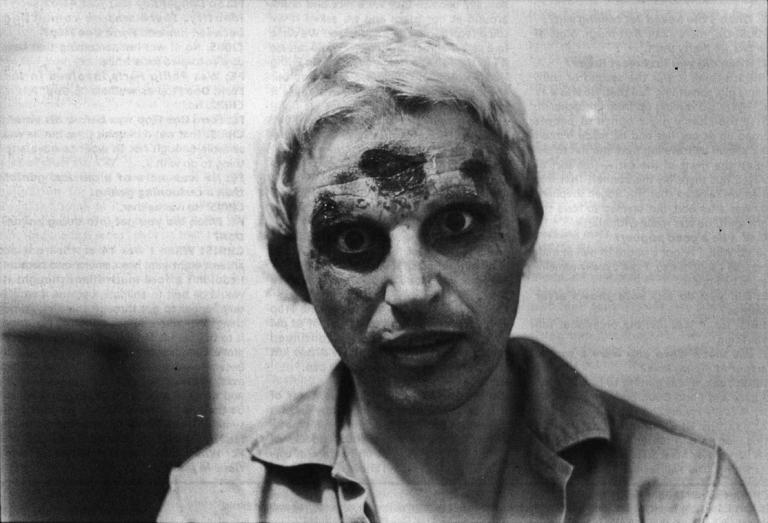

My definition of this tendency draws heavily on an analysis of the audio and film works of Chris Knox. The emergence of this artist from the milieu of post-punk popular music in New Zealand marked the explosive growth in the influence of the mis-competent virus.

By 1980, the cultural revolution of punk was over in Europe but still working itself out in New Zealand. The UK had seen a great upswing in DIY activity with independent labels mushrooming as artists organized to manufacture and distribute their own work; an approach that had never been taken before on any real scale. This phenomenon got underway in New Zealand in 1978, in Auckland, and quickly spread.

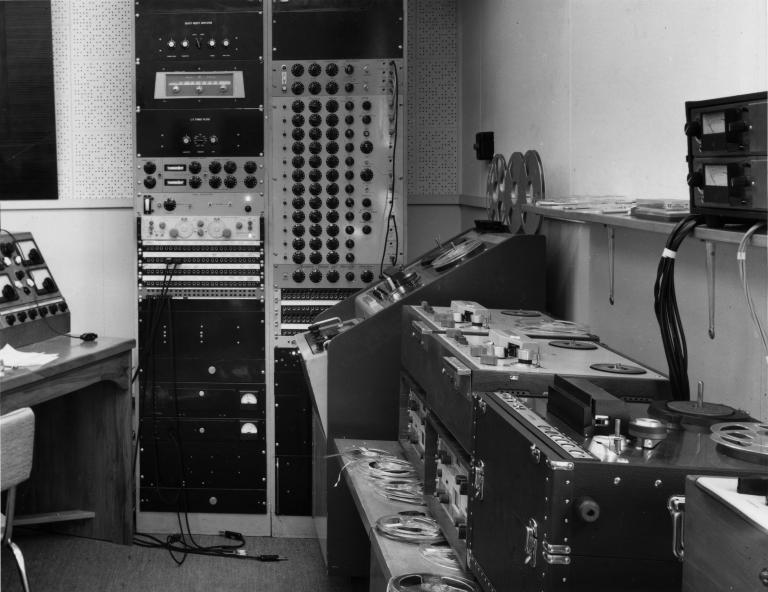

Chris Knox and Alec Bathgate had started their careers in The Enemy, an influential Dunedin punk band, and then recorded several singles and an album for WEA with Toy Love. After the experience of the eponymous Toy Love album (1980), they took the decisive step of abandoning studio recording, considering it an obstacle to self-expression.

Knox purchased a TEAC 4-track and taught himself to use it. Crucially, his only real skills at that time were as a vocalist and lyricist. He not only knew nothing much about audio engineering, he couldn’t play any instruments. As a result, he turned to kitchen-sink experimentation, using many of the same simple manipulations earlier employed by Lilburn, including the looping of sounds, which Knox was to raise to the status of a signature gesture (Coley, 2012).

In early 1981, Knox and Bathgate (as the Tall Dwarfs) released a twelve-inch EP called Three Songs on the Furtive label and unknowingly started a cultural revolution. The recording methodology used on this record was essentially the direct opposite of everything “real” engineers do.

The process was documented on an insert included with Tall Dwarf’s 1982 follow-up record, Louis Likes His Daily Dip, on Flying Nun. Three Songs exemplifies the mis-competent approach to playing. Bathgate deliberately used an almost untunable acoustic 12-string with unfeasibly high action, simply because he had no money and thought it sounded cool when close-mic’ed.

This approach was also applied to marketing (a cover with unintelligible and “off-putting” pen and ink drawings with the band name hidden), and promotion (no live performances, but a stop-action film of unruly domestic appliances was shown on bemused pop music TV shows). With one stroke, mis-competence was related directly to not only the Antipodean DIY myth — a romantic conception of New Zealanders as uniquely possessing ingenuity and resourcefulness, able to make do with whatever scrap materials are at hand — but also the punk ethos of “just doing it” and “sticking it to the man”.

This record, quickly followed by numerous recordings made by Knox for the Flying Nun label, established and popularized an already latent tradition of self-recording and audio experimentation in New Zealand. This tradition was “sold” to a receptive generation by a charismatic artist who already had their admiration through his earlier “legitimate” career as a rock star.

It was also in crucial part communicated orally, as Knox taught Peter Jefferies of This Kind of Punishment, who moved to Dunedin and in turn worked closely with the likes of Alastair Galbraith and Michael Morley. And these people, having the means to release recordings on the fringes of post-punk rock music, made the leap into fully improvised sound as well as DIY recording.

In this way, improvisation became both the technical support for the work, as it had been for Lilburn, and also, increasingly, how the work was carried out, as more and more essentially untutored experimentalists began “making noise”.

What is instructive in this story is how little it took to enable this shift to home recording and then improvisation. The verbal transmission of a limited repertoire of technical knowledge by a handful of people started a pattern of cultural production that rapidly became widespread.

The technology already existed, as it had during the 1960s, though it became more portable and affordable as time went on. But technology alone is never enough to enable cultural progress. There also has to be a shift in the habitus associated with the technology; the necessary social relationships, ideas, and socially probable outcomes must also exist before a possible mode of activity can become likely or widely accomplished.

It was through this sequence of events that the kernel of stoically individual DIY technical improvisation latent in NZ culture (which we might call the “Richard Pearse spirit”), infected “music”, and in this way self-recorded and improvised sound work became the widespread cultural meme that it is today.

The ubiquity of this attitude is reflected in the fact that even when properly “musical” instruments are used, the concern of the artists is often focused on the sounds of “misuse”. Witness the employment of electric guitars as drone sources in the work of influential '90s artists such as RST and Surface of the Earth; this is a style of playing that derives in part from tabletop methodologies and is often completely “hands-off” — the guitar may not be “played” or indeed touched at all.

Once the benefits of mis-competent strategies became apparent, their spreading popularity was assured. The establishment of the Xpressway label in Dunedin in 1988 was important in keeping this alternative approach in view at a time when the “popular” underground was starting to resemble the regular music business. Big studios and budgets now came within the reach of many who had to that point been forced by circumstance to follow a DIY strategy.

The rapid success in attracting international attention by those artists who quite intentionally chose the mis-competent strategy was spearheaded by The Dead C (a wholeheartedly mis-competent enterprise whose raison d’etre was to confound all legitimate expectations of a rock band).

Once a flood of US releases by this self-evidently mis-competent ensemble began to re-enter the New Zealand market, others began to take note. Indeed, even the strategy of ignoring potential success in the local market — instead linking horizontally to independent labels and distributors in other countries — is a counter-intuitive piece of mis-competence that flew in the face of received wisdom about how commercial careers were made.

The sheer number and variety of artists at least partly inspired by the example of the Xpressway group is documented in the Audio Foundation/CMR publication Erewhon Calling (Russell ed., 2012). A classic example is the work of Campbell Kneale, who since the early 1990s has moved from sub-Husker Du alternative rock to uber-ambient sound sculpture, releasing a baffling slew of titles, and collaborating internationally with artists as diverse as Tony Conrad, Lee Ranaldo, and Anla Courtis. One might equally well point to the work of Stefan Neville, Peter Wright, or Matt Middleton, also covered in the Erewhon book.

In part, this explosion of creativity and effort took place because improvisational mis-competence married so well with the whole “auteur” — or artist/producer/distributor — strategy. Taking complete control of production was a de facto political position with respect to the music industry (established labels, distribution channels, and their symbiotic integration with all media). As a result, “doing it wrong” became a clear signal of orientation concerning a relationship to the intended market or audience, as well as a way to achieve desired outcomes “on the cheap”.

The initial flowering across New Zealand of what became known as “free noise” (an improvised meta-music of sounds both “musical” and mis-competent) was defined and encapsulated in the 1996 album Le Jazz Non: A Compilation of Nineties NZ Noise (Corpus Hermeticum).

This compilation traveled widely and assisted a raft of “bedroom artists” in establishing international recording and touring careers, well outside the sphere of the rapidly developing New Zealand music industry. While the actual music varied in style and instrumentation, there was a coherence of approach that emphasized collaboration, independence, home-recording, electronic or electro-acoustic means, and a wholesale rejection of “musical ability”.

The subsequent growth of this pragmatic experimentalism in sound has, of course, been a factor in the simultaneously increasing integration with international networks and touring options, yet the overwhelming impact has been seen to be that of a defined “national tradition” of sound experimentalism.

This has been in turn supported by local initiatives such as (among many others) the Audio Foundation, the Lines of Flight festival, the Borderline Ballroom collective, and underground venues such as the Frederick St. Sound and Light Exploration Society. More details could be adduced to support the overall thesis, but such multiplication of prima facie evidence is pointless. The historical record is, at this point, clear.

Bruce Russell, Lyttelton, 2012

References

Coley, B. (2012). Chris Knox Told Me. In B. Russell (Ed.), Erewhon Calling: Experimental Sound in New Zealand. Auckland, New Zealand: Audio Foundation/CMR.

Lilburn, D., & Harris, R. (2004). Liner notes to Douglas Lilburn: Complete Electro-Acoustic Works. Auckland, New Zealand: Atoll Recordings.

Russell, B. (2010). Too Reel: Thoughts Occasioned By the Belated Release of "A Bun Dance" by John Pilcher and Martin McKelvey. In B. Direen (Ed.), Landfall (219). Dunedin, New Zealand: University of Otago Press.

Erewhon Calling: Experimental Sound in New Zealand. Auckland: Audio Foundation/CMR