“ ...Orpheus looked back and thus screwed things up. What we encounter here is simply the link between the death-drive and creative sublimation: Orpheus’ backward gaze is a perverse act stricto sensu, he loses Eurydice intentionally in order to regain her as object of sublime poetic inspiration...”

Slavoj Žižek

“With enormous night I am borne away,” laments Eurydice, as she is taken by underworld darkness — darkness depicted in book four of Virgil’s “Georgics”. The fatal scene is staged in perpetual twilight — in a borderland, between the realm of the living and the dead. Orpheus’ loss of Eurydice: the tragic after-effect of a divinely forbidden rearward glance. The anti-hero’s insubordinate retrospect — a fateful consequence of Orpheus’ involute grief and desire.

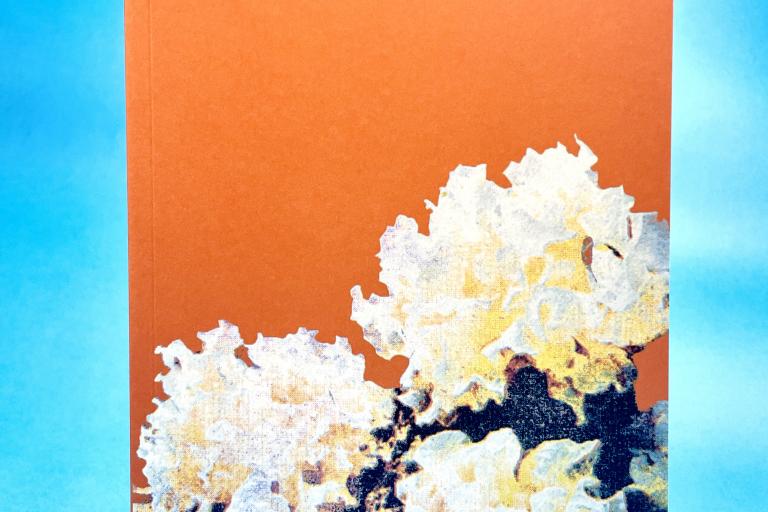

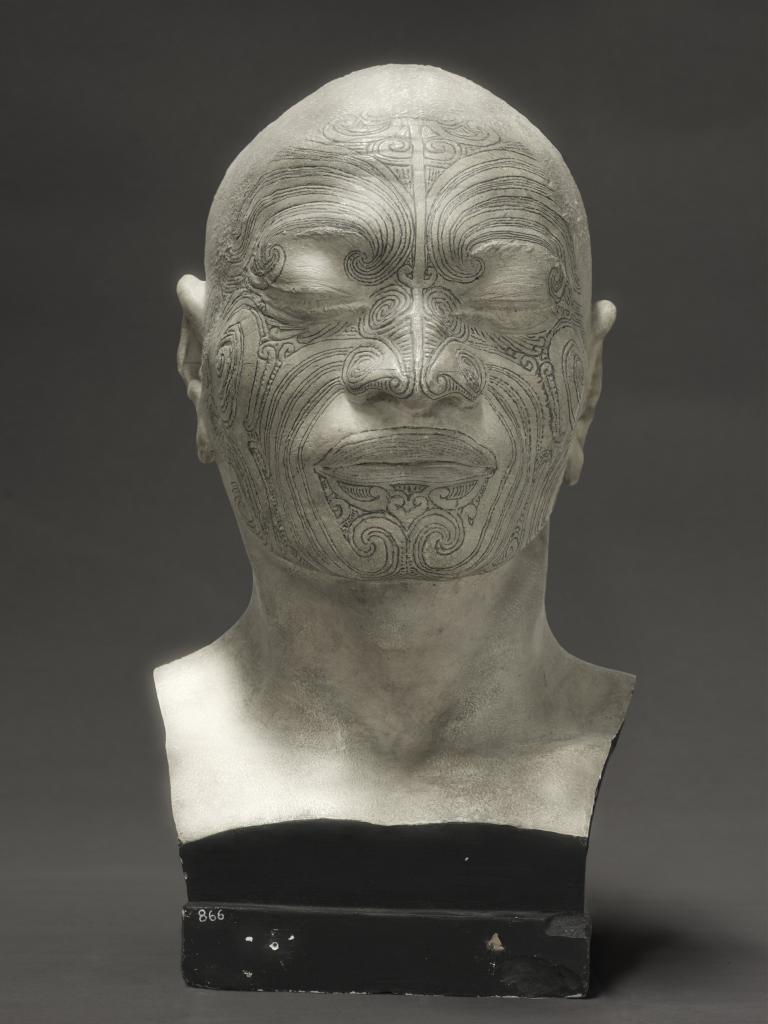

A facile viewer of Fiona Pardington’s avidly materialist, but elegiacally commingled, still lifes might fall victim to fatal assumption. Succumb to the deadening notion that the artist’s images are little more than backward glances — nostalgically desirous epicurean photo transcriptions of antedated nature morte. They are that and more. Profoundly more.

A sybaritic eye drives Pardington’s retrospective consideration of an optically sumptuous genre. However, that same ardent orb is struck through with knowing pathos — with unappeasable longing. Sophisticated viewers, sifting through Pardington’s photographs, will find rich arrays of art-historical genotypes — identifiable pictorial categories from which the works branch, flower, and fruit. But tracing backward — from the furthest florid reaches of the photographer’s historically trellised images — toward their mortal rootstock, is another, more zoetic matter.

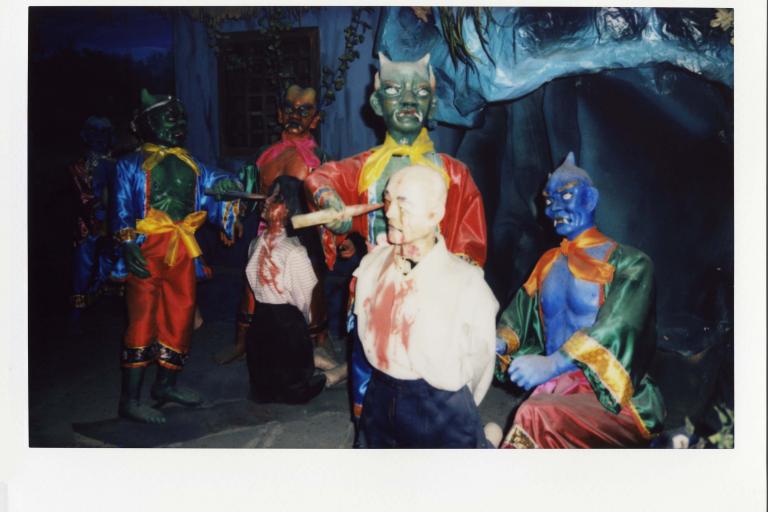

Artists of the Roman Empire anticipated still life painting as a genre. Their anticipatory pictures, described at times as vanitas, were optically frugal arrays, often underwritten with the acerbic axiom: Death makes all equal.

Much later, across seventeenth-century Europe — conspicuously in the prospering cities of the Northern and Spanish Netherlands — nature morte reached its aesthetic zenith. A surpassing number of seventeenth-century still lifes could be fairly categorized (Cotán and Zurbarán being abstemious exceptions) as opulent and carnal — in celebration of the newly flush urban mercantile class’ domestic surplus. But there were, too, in these otherwise optimistically feting pictures, surreptitious memento mori. Pictorial footnotes (cautionary skulls, vermin, and evident decay) mordantly attesting to the temporality of all things.

De trop banquet spreads were the fashionable subject of seventeenth-century still lifes. But the content and subject-laden ceremonial banquet — as it emerged formally ordered from the medieval sixteenth century — was a foundationally soberer affair than one might imagine. A graver, more ritualistic event than popular imagination would have it. Formalized seventeenth-century feasts evolved, arguably, from earlier medieval Ceremonies of the Void; elaborate, symbolic dinners, at the end of which après-repas guests stood away from the table and toasted — like farewelling mourners at a wake — while the feasting board was cleared or, rather, “voided”.

These emblematically melancholic feasts, and the still life paintings memorializing them, spoke, and speak yet, to mortal extremes. Vacillating between the heedless profligacy of the human appetite and the ceremoniously deferred austerity of the void — of non-existence itself. Feast and painted transcription, shuttling fatalistically, in living imagination, between worlds of light and dark.

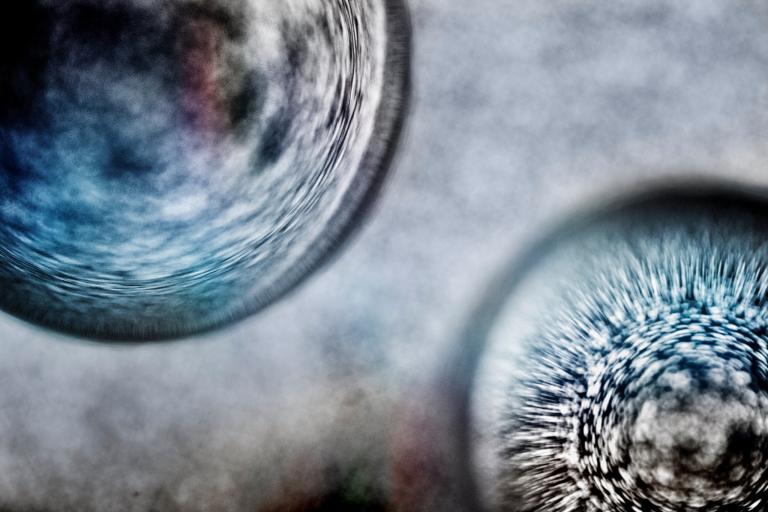

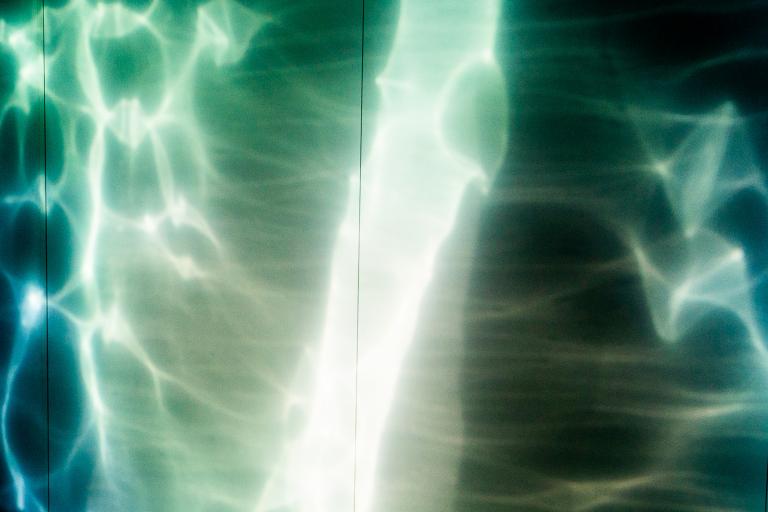

Perceptual phenomenology’s introspective model of an incident-inhabited world — a dualistic realm, enveloped by light and its shadowy double — encourages us to note, while waxing poetic about chiaroscuro, that the eye, if ruled by either light or dark extremes, is incapable of perception.

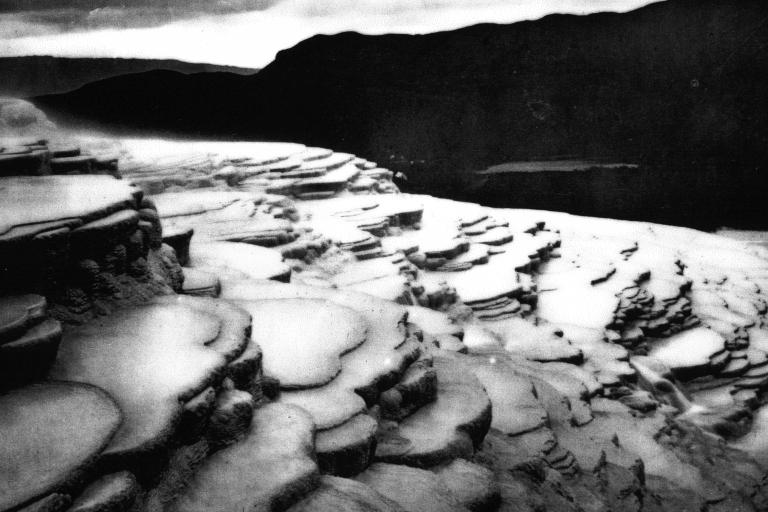

Blinding polar whites overwhelm and the absence of visible light presents to the eye as black, illimitable space. Somewhere, anywhere, between the white-hot promontories of perceptible chroma and the lowermost achromatic sumps of imperceptible light, there is situated the visually negotiable (and desirable) midlands of discernible creation. Retreating, a sensible distance from the illiterate intensity of pure white and the black cloud of unknowing... eye, artist, and audience instinctually seek a salutary middle ground.

Middle ground, as applied here, to Fiona Pardington’s ongoing visual investigation, alludes to something other than aesthetic casuistry or contrivance. To something more than glibly arbitraged capitalization on the discrepancy between dark and light. Pardington’s all-in images are anything but risk-hedged in terms of their aesthetic aims or attendant objects. The artist’s risky ways and material means are literally, figuratively concentered — making cartographically adroit camp at precise intersubjective crossroads of light and dark.

With veteran shadow play, precariously balanced formality, and calibrated improvisation, Pardington retrieves and composes integral parts of an otherwise “unfinished world in an effort to complete and conceive it”. What I mean to suggest here, in abducting Merleau-Ponty’s theoretical poesy “unfinished world”, is a sort of pointing-at-dawn-horizon allusion to the Genesis-like formative (and darkness-defying) goings-on in the transactional half-light of Pardington’s pictorial spaces.

“And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep.”

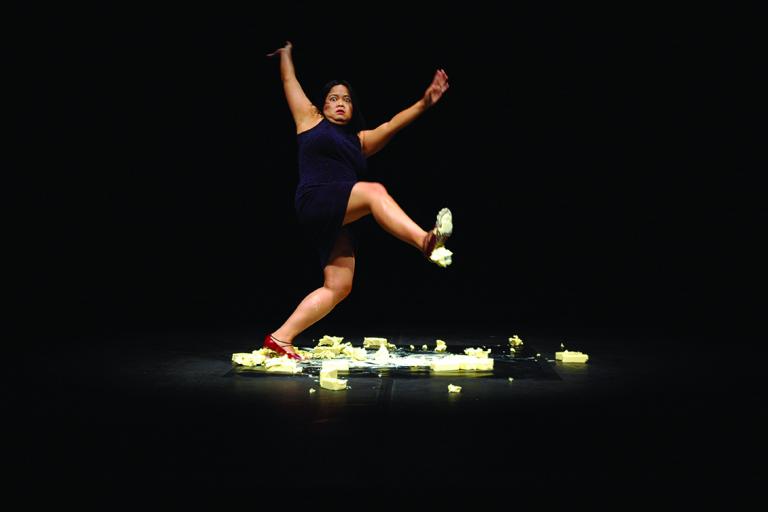

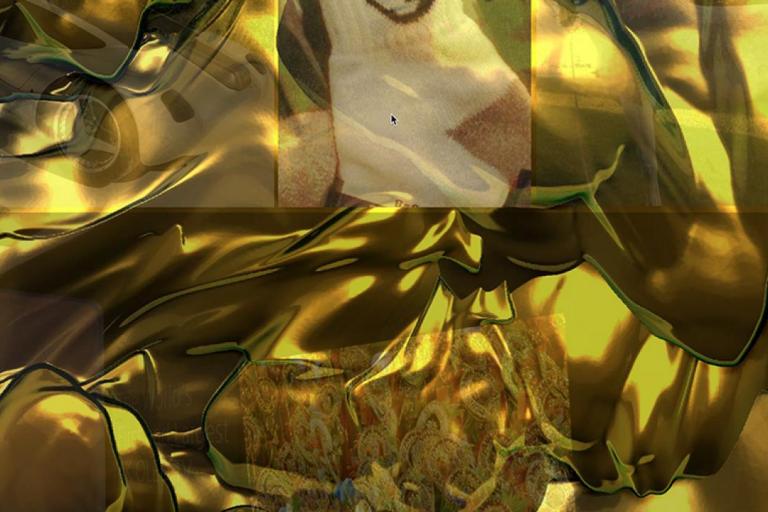

An artist’s bromidic, god-like relationship with their own creation trades in the cognitive music of comings and goings — in decisive strophes and fugitive fermata. Artist and work moving symphonically to a common melody. Practice and practitioner, partners in a temporally scored pas de deux. Subject and object obliged by Chronos to come into and go out of being. Nacreous fellow forms birthing into bister — edging from crepuscular, to partially eclipsed, to full light — while other mortally subject forms are synchronously, and just as indifferently, delimited and variously devoured — swallowed by the pictorial space’s accommodating darkness.

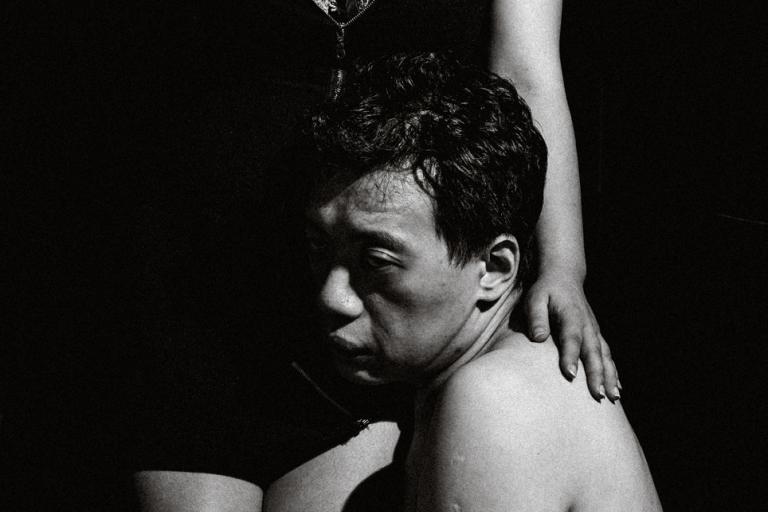

Pardington’s Caravaggesque, stage-lit forms derive much of their lifelikeness from a sort of saturninely metered, theatrical movement — their halting anecdotic action suggesting serially adumbrated forms engaged in a glacially cadenced processional march — out of, and back into, dilute background ink.

By contrast, pre-baroque (High Renaissance) painting’s faux-naturalistic convincement could be fairly characterized as generally reliant on a preternatural quality of diffuse inner incandescence — landscapes, figures, and inanimate objects alike, collectively absorbed in a democratically luminous communion — a homogeneously burnished Eucharist of consecrated light.

The sfumato, sleight of hand — the metaphysical conceit — of Renaissance painting, depends on a stylized lack of distinction between phenomenal (natural) and transcendent (preternatural) light... its theologically driven lack of phenomenal discrimination privileging, by default, metaphysical, over physical light.

Pardington and Caravaggio’s approach to light (and darkness) is equivalently partisan and divergently secular. Both artists’ stylistically identifiable tenebrist lighting, and eroica-like corporeal movement, propose a celebration of, or at least a resignation to, a kind of wholesale quotidian anti-apotheosis. An unapologetic acclamation of here-and-now bodily “thingness”.

Both artists’ pictorial constructs rely on a sort of amor fati — an audacious “through a glass darkly” veneration of things and their inviolable circumstance — things fatally contracted to (and authentically ballasted by) the circumstantial way of all flesh. A pictorial language wholly disinterested in what my young son once malaprop(ed) as “special futures”.

Poussin, via André Félibien, viewed Caravaggio’s arrival in the world of plastic arts as an oracular prediction of painting’s imminent destruction. Vincenzo Carducci suggested that Caravaggio's audience's quickening “false miracles and strange deeds” were aesthetic-apocalypse-heralding signs and wonders. Dark portents — from a forerunning pittura-antichrist. Caravaggio’s canvases, however spectacular and emotionally moving, were posited, by Félibien and Carducci, as nothing more than devilishly deft technical pyrotechnics designed to diabolically deceive.

I would speculate — albeit with scant scholarly credentials or intellectual rigor — that these (and other) convulsive receptions of the Baroque painter’s light-cannibalizing canvases were ideological (or rather, theological) sublimations of horror vacui. Fear of the virtuoso painter’s anti-redemptive signs and wonders. Horror begot of the painter’s voraciously consumptive, and carnally birthing, voids.

Caravaggio’s project was — as Simon Schama once had it — to “paint himself out of trouble”. I would suggest that Pardington’s creative problem (i.e. trouble) is — much like Caravaggio — the shared human dilemma of death foretold.

Surveying back over Pardington’s presentational permutations, one is struck by the artist’s promiscuous range of subject matter, contrasted with an almost monogamous constancy of context... as revealed by her (shall we say) funereal stagecraft. More often than not, Pardington’s artfully directed subjects slip toward us somnolently from the plush nether-folds of dark, mediating curtains. And, just as compliantly, settle into the ground’s soft chthonian folds… as if taking a final cosseted rest. Her life and death masks are posed, as if in requiem drama, against tellingly indifferent sepulchral planes.

I would submit that death as subject, content, or inescapable fact of life, is best mediated by creative genius — given great creative works possess a singular capacity to arrest and capture whole, and intact, the profound nullity of things... to speak lucidly and comprehensively to our mutual condition. To candidly confirm humankind’s innate consensus understanding of its preordained unhappiness — to honorably attest to the inevitability of individual and collective suffering and ends. While doing so, these consummate creative testaments afford us collateral solace and, with their dark servings, whet our appetites for what’s left to us of life.

“Now it’s dark.”

Correggio, with his life-sized “Jupiter and Io”, personifies the painting’s ground. Literally. Depicting Jupiter as a ground-birthed, pictorial-space-consuming, and anthropomorphic Payne’s Gray cloud. Divine-as-consummating cloud: simultaneously attending the picture as stage, set, and actor. As both figure and ground. A margin-pushing nimbus, serving as chief agency of space, time, and mood in a painted interpretation of Ovid’s metamorphic mise en scène.

Setting — pictorial ground, weather, time of day, quality of light — has been, and is, inexhaustibly transubstantiated by painters, filmmakers, writers, and photographers. Chronically called upon — cross-genre — as pervasive, defining atmosphere, and as supporting, or chief, dramatis personae. Setting, enlisted as stand-in for character.

Where would David Lynch be without his ominously eclipsed middle-class day... or “bread crumb trail” of beguiling nocturnal artifacts, leading through a suburb’s thin veneer of light... to ever-present, awaiting, primordial darkness.

What more distinguishes film noir as a genre than its architecturally raking shadow? Architectonic penumbra mimicking a gnomon’s time-marking mechanism: its shadow-casting chronometric function, filmically conscripted to compress, accelerate, and intensify filmed drama’s generously mutable allotment of time.

Andrei Tarkovsky’s often-oneiric filmic passages are largely reliant on dramatic but temporally languid tonal shifts. The filmmaker’s screen projections act as stygian basins: dark rectilinear pools, from which things miraculously breach, bathe in fatalistic shadow, and drop irretrievably away.

To similarly fateful and evocatively moving ends, Fiona Pardington masterfully symphonizes her quadrilateral Cimmerian fields.

Coda

“Tasso... It seems to me that la noia is of the nature of air. Which fills up the spaces between material things and all the voids in each one of them; and whenever a body changes its place and is not at once replaced by another, la noia at once comes in. So all the intervals in human life between pleasure and pain are occupied by la noia...”

From Giacomo Leopardi’s “Dialogue Between Torquato Tasso and His Familiar Genius”

Eighteenth-century lyric poet Giacomo Leopardi’s “Dialogue” here personifies what he sees as boundless, yet somehow fatally subjugated, human desire; naming it la noia — assigning to it definable characteristics. Leopardi collectivizes its aspect as “the stuff of which human life is made”. Going further to describe la noia as a sort of climatic ground from which existence itself is fashioned of, surrounded by, and interpenetrated with.

The epic poet, by attributing to his la noia the mechanism of “inspiration” — fills up the spaces between material things and all the voids in each — obliquely identifies the objective (or bodily) nature of his paradoxical muse and desire. In art as in life — no object, no desire; no desire, no poetic inspiration; no inspiration, no expression; no expression, no art.

Leopardi’s distinctive lyric style — born of his own physical, human incapacity — invents a verse form that is a sui generis nomenclature of private and, by implication, universal anguish. Anguish, according to the poet, wrought of unmitigated longing: desire for an infinite procession of enthralling, but mortally foreclosed, objects.

Fiona Pardington takes it upon herself to hazard a gimlet-eyed retrospective look at a replete array of desirous objects — things inextricably bound to finitude. She unflinchingly undertakes an exhaustive inventory — a poetically transformational retrieval and reconstruction of all she longingly surveys. Fashioning, from the very things of her (and our) undoing, impeccably crafted vehicles of consolation.