This article was written in 2016 and first published in the 15th print issue of White Fungus.

Tourists still roll up in taxi buses and wander through the place, sometimes chatting to Pilioko, now in his eighties, who continues to paint every day. But the life of Esnaar, at least as it was, is drawing to a close. The property today is mostly a palimpsest of its past: exotic plants brought back from travels abroad have grown into enormous trees; former studio and dwelling places have been repurposed or left abandoned; guest and entertainment facilities are now rarely used.

Among these structures is an old shed, formerly a painting studio, housing the remains of Michoutouchkine’s once-vast collection of Oceanic artifacts, gathering dust in the tropical heat. They are the remnants of his grand ambitions, among them the desire — never quite realized — to create a museum of Oceanic art in the Pacific Islands for Pacific Islanders.

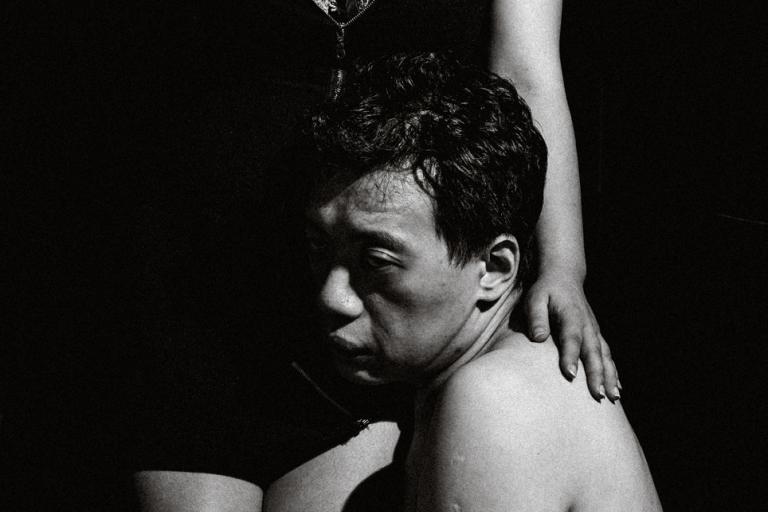

Pilioko and Michoutouchkine were an unlikely couple from opposite sides of the world with complex backgrounds. Both were subjects of historical diasporas: Michoutouchkine of Russian Cossacks after the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution; Pilioko of Polynesian migrants after World War Two. Both experienced the intrusions of that war: Michoutouchkine as a teenager in Nazi-occupied France; Pilioko as a boy when thousands of American troops were stationed in the South Pacific, including his home island of Wallis. Both were gay. And both were travelers.

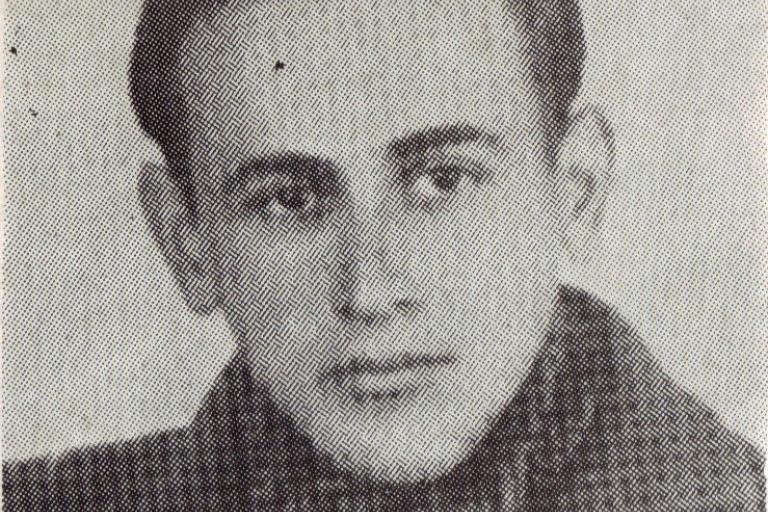

Michoutouchkine was the son of Russian Cossacks — his father a soldier and his mother a nurse — who had independently fled the aftermath of the revolution in 1920, met and married in Turkey, and eventually settled in Belfort, France, where the artist was born in 1929. The repercussions of that history — the trauma of his parents’ exile, the loss of a homeland, and the displacement of the language, culture, and religion of his heritage — were no doubt formative of Michoutouchkine’s outlook on the world, influencing his life as a traveler. In 1953, he left Paris at the age of twenty-four on an open-ended adventure that he would later call his “pilgrimage to the East.” [1]

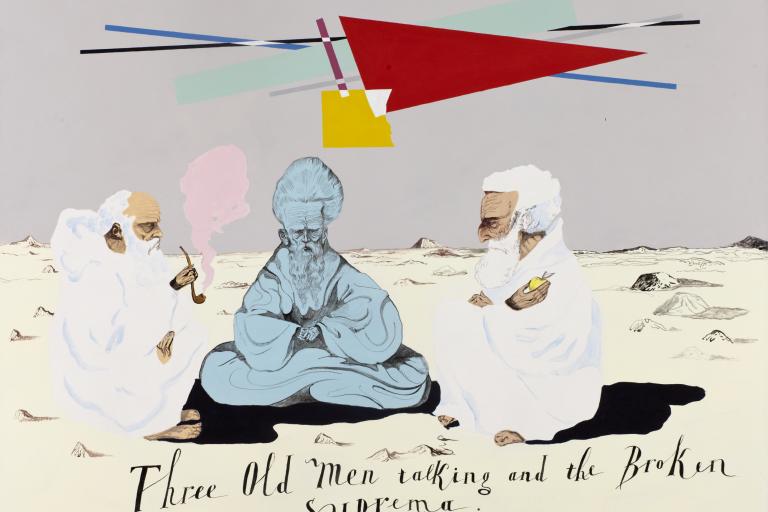

He traveled through Italy, Greece, and the Middle East (Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, Israel, Egypt, Iraq, Iran, and Afghanistan), then spent two years traveling through India, making excursions to Nepal, Burma, Ceylon, Thailand, and Vietnam. To some extent, these travels had the character of a spiritual quest. The artist spent time with Christian Orthodox monks on Mount Athos in Greece and again with Buddhist monks in the Himalayas. He made pilgrimages to Buddhist holy sites in India and Burma. He staged improvised exhibitions en route based on paintings of local holy sites and religious landmarks. On the other hand, there was also something much more profane about his travels. They began as a correspondent assignment for a Parisian newspaper. He was the generator of “news” and himself the subject of news about his travels or exhibitions in local newspapers wherever he went.

Michoutouchkine’s travels and exhibitions were facilitated by contacts in embassies, consulates, and international organizations like Unesco, the Alliance Française, and the World Fellowship of Buddhists. Political and religious leaders — from the Shah of Iran and the King of Jordan to the Prime Minister of India and the Dalai Lama — received him or visited or opened his exhibitions. Indeed, fraternizing with political elites and co-opting the patronage of national organizations to stage cross-cultural exhibitions would become his modus operandi for the rest of his life.

The course of Michoutouchkine’s life would change, however, after his arrival in the South Pacific in 1957. That year he was compelled to leave India and re-enter French territory in order to fulfill military service obligations. He did this by flying to Nouméa, New Caledonia, where he ingratiated himself with the governor of the territory, who employed him as a special secretary and translator.

His sojourn in New Caledonia affected his life in two crucial ways. First, it refocused his traveling ambitions on the Pacific Islands and precipitated a new-found passion for collecting local examples of ethnographic art. (His first pieces were acquired in the course of official visits to rural Kanak villages.) Second, it occasioned his meeting with Aloï Pilioko, who would become his artistic protégé and lifelong partner.

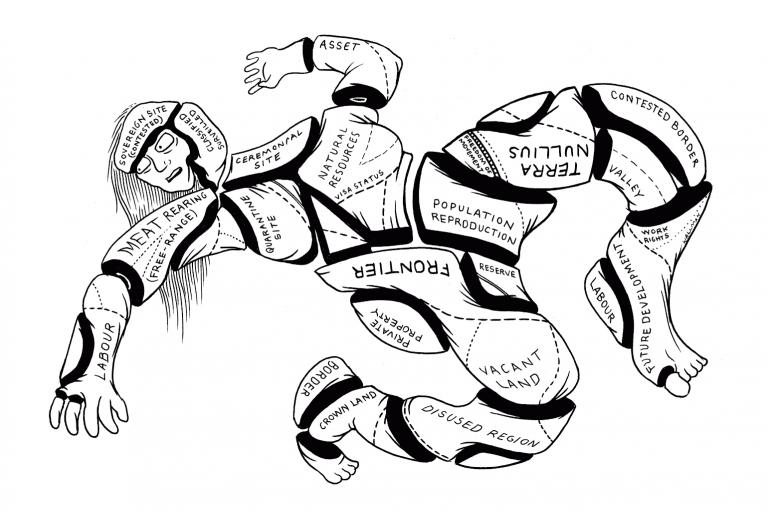

But to understand their project together, it is important to see it in a broader context. Michoutouchkine’s travels were part of a wider social phenomenon observed by Levi-Strauss in his book Tristes Tropiques (1955), where he notes a “renewed vogue in contemporary French society” for young adventurers — “modern Marco Polos” — to fan out from Paris and other metropolitan centers to remote corners of the world in the continued quest for the exotic or supposedly still-“primitive.”

Levi-Strauss disdained these modern travelers, whom he saw as deluded fantasists. In his view, the expansion of Western imperial civilization had resulted in the destruction of genuine forms of “primitive” life. The globalized civilization taking shape after World War Two was one that was utterly and irrevocably “contaminated” by this destructive history, “a proliferating and overexcited civilization” which had “broken the silence of the seas once and for all.” [2]

Yet the lament is obviously problematic. It seems as invested in the dubious idea of the “pure” or “innocent” Native as the deluded fantasists he disdains. Indeed, their delusion is the mirror of his disillusion with precisely that “pure” ideal, which was as much the object of his lament as the realities to which it referred.

Levi-Strauss was right, however, in that the idea of the “primitive” had assumed a strange kind of second life in the post-war decades, recoded by the tourism industry, fashion design, the tribal art market, new museums, “primitive art” exhibitions, commercial travel, and newspaper and magazine features on the “last” this or that. The French Pacific was a particular hotbed for romantic fantasists “escaping civilization” in the towns and tropical beaches of the region at a time when colonial hegemony was still in place.

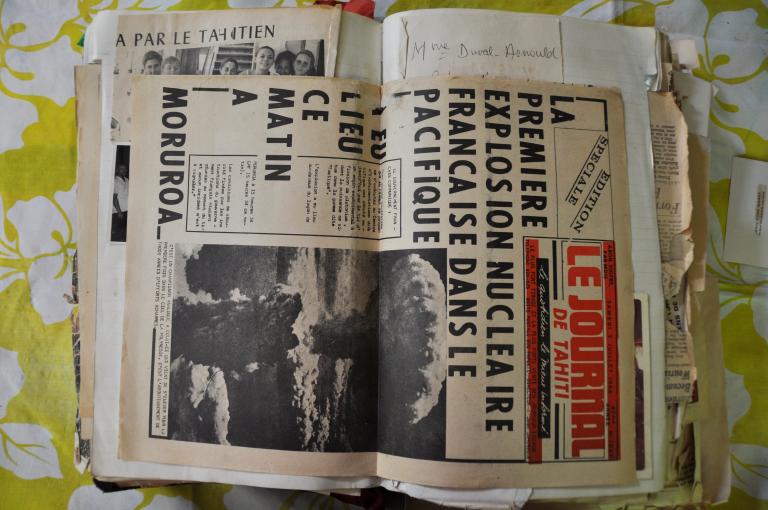

French investment in the expansion of a tourism economy in Tahiti and the Society Islands, capitalizing on their legendary stereotype, and a military complex to support its nuclear testing program on Mururoa Atoll in the 1950s and 1960, brought thousands of expatriates to the region, including many artists drawn by the example of Paul Gauguin and the modernist admiration for Oceanic art. Michoutouchkine no doubt shared these attitudes and perceptions. But the arc of his life in the Pacific was shaped by decades of acquaintance with its heterogeneity and complex modernity.

His travels might be better understood not as deluded escapism, but as part of the global dissemination of modernism at the time, as the confluence and cross-pollination of Western modernisms with modernist movements and aspirations — some nascent, some already decades old — in other parts of the world. Nouméa, Papeete, and Port Vila, for example, were nodal points in an active network of expatriate, local, and traveling artists working in the region, including a handful of urban Islanders.

Michoutouchkine’s arrival in Nouméa was a galvanizing force in this milieu. He befriended locals, socialized with influential elites, encouraged aspiring artists, staged exhibitions, and in 1959 set up an independent art gallery — the first in the Pacific Islands — in an old colonial villa. There he met Aloï Pilioko, a migrant labourer working on a nearby building site. A curious man, Pilioko was attracted by the sociality of the gallery and riveted by the artworks on display — unlike anything he had seen before. Michoutouchkine befriended him, the story goes, and encouraged his desire to draw and paint.

Pilioko had left Wallis in 1957 as part of an out-migration of young Wallisian men seeking work and opportunity in the wider territory (first on Efate in the New Hebrides, then New Caledonia) after the relaxation of colonial labour laws (one of the first moves towards decolonization in the French Pacific). He was also a gay man escaping — or at least taking his distance from — the hegemony of colonial Catholicism on Wallis, a French protectorate since the 1880s and Roman Catholic since the 1840s.

That is to say, Pilioko was not an Islander encountering the modern world as if for the first time. While life in Wallis was village-centered and pervaded by Indigenous ways of living, it had nonetheless been transformed by colonialism and modernity. Nor was he just a plantation worker or a labourer. Pilioko was also a “modern Marco Polo,” on a journey of possibility and self-discovery in the postwar era. His encounter with Michoutouchkine in Nouméa was a serendipitous meeting that marked the beginning of their friendship. Their formal partnership, however, came about somewhat later.

Michoutouchkine’s gallery in Nouméa was a short-lived affair. He closed it a few months after it had opened in order to take a position as the manager of a trading company on the island of Futuna, involved in the purchase of copra. In reality, however, Michoutouchkine was continuing the pattern of his travels, though now with the additional goal of expanding his collection of Indigenous forms of art. Soon after he left, Pilioko visited him in Futuna while en route to visit relatives in nearby Wallis. The visit turned into a two-year sojourn together, painting, exploring, interacting with the locals, and consolidating their future partnership. [3]

The sojourn in Futuna was a turning point for both artists. For Michoutouchkine, it changed the character of his traveling adventure, displacing its aimlessness and transcendental escapism with a sense of purpose it did not have before. Now he would act as Pilioko’s mentor, manager, and promoter. He was also determined to amass a grand collection of “Oceanic art” from the islands around him, an ambition in which Pilioko would serve as a useful go-between and traveling companion.

The collection would form the basis of traveling exhibitions that would feature the work of his protégé and his own (along with that of a handful of other contemporary artists, Indigenous and European). Furthermore, the exhibitions would be the vehicle of his return to France and open the way for further travel around the world. Finally, the collection would form the basis of a museum of “Oceanic art” in the Pacific Islands.

For Pilioko, the sojourn in Futuna consolidated his ambition — unprecedented for a Pacific Islander at the time — to become a modern artist. In 1961 their project began in earnest. They left Futuna and resettled in Efate in the New Hebrides (now Vanuatu), where they acquired Esnaar — a property that could serve as their joint studio home, storage facility, and base of operations. For the next six years, they embarked on an intensive period of traveling, collecting, exhibiting, and making art through a vast swathe of Pacific Islands, before leaving for France in 1967.

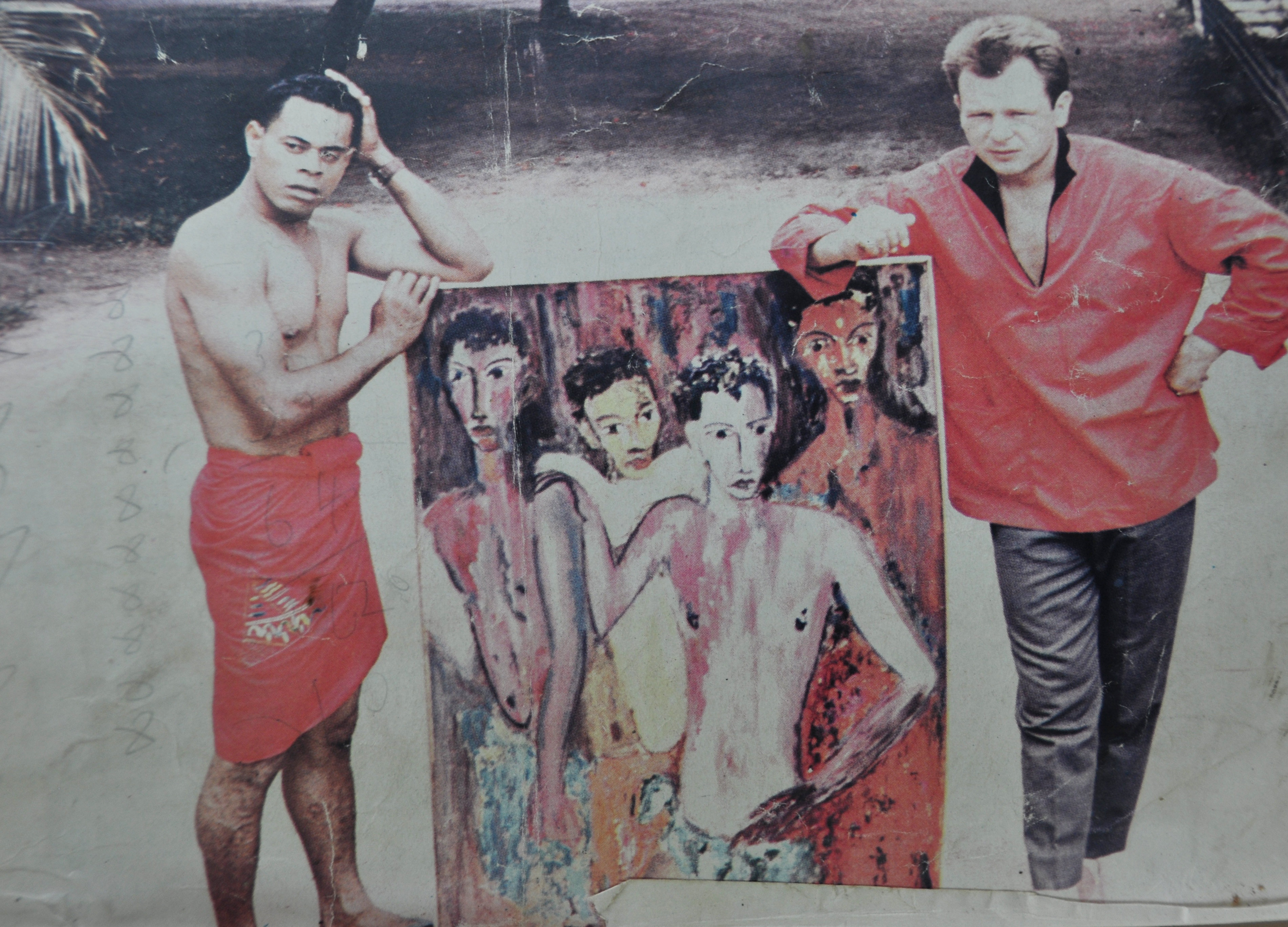

Their travels began in the French Pacific — the New Hebrides, New Caledonia, and the Society Islands — moving between exhibitions in the main towns — Port Vila, Nouméa, and Papeete — and collecting forays into the surrounding archipelagos. The township exhibitions — staged at the Port Vila Cultural Centre, the French Institute of Oceania, and the Papeete Museum, respectively — marked Pilioko’s public debut as an Indigenous artist working in a Western mode.

Expanding the scope of their travels in 1963, they visited the British Solomon Islands, including “outer islands” like Tikopia, Santa Ana, and Bellona. The following year they exhibited in Adelaide, Sydney, Canberra, Tonga, and Fiji, and mounted several major collecting expeditions to eastern New Guinea in 1964, visiting the Admiralty Islands, the Maprik region, the Sepik, and the Highlands. In 1965, they visited Rotuma, Samoa, Wallis and Futuna, every one of the Marquesan Islands, and in 1966 returned to exhibit again in Papeete, Noumea, and Port Vila.

They traveled on passenger ships, inter-island ferries, cargo boats, motor scooters, commercial airlines, private schooners (on which they hitched rides), and whatever other means of transportation could be co-opted for their purposes. They used diplomatic contacts, church networks, and personal referrals to mount ad hoc exhibitions in colonial museums, town halls, school rooms, airport lounges, churches, ship cabins, villages, hotel lobbies, and the like.

Everywhere they went, they made friends with locals, shared food, toured sights of interest, and collected artifacts of every kind through purchase and gift. En route, they met and inspired local artists like Tivoa Vise in Tonga, Semisi Maya in Fiji, and Henry Gibson in Rotuma. They introduced the idea of "art" and exhibition value into local communities and avowed as the aim of their exhibition to “cultivate cultural revival.”

Pilioko’s role in these travels was crucial. His presence opened doors of welcome that might have remained closed if Michoutouchkine had been on his own. He was also showing his friend his regional “neighborhood” at the same time as he was discovering it for himself, exploring a world of ancestral cousins who lived in tropical villages like his own and had comparable languages, cultures, and colonial histories. The experience also confirmed his sense of his role as an artist of the region, immersed in and witnessing its heterogeneity and complex modernity.

The period was also one of intense artistic experimentation for Pilioko as he began to search for more adequate formal means to represent his encounter with the Pacific and himself as an Islander. It was in Rotuma in 1965 that he made an artistic breakthrough in the invention of his so-called “needle paintings” — tapestries embroidered with colored wool on sacking from copra bales.

The technique came from the modernity of the Pacific, with coloured wool having long been adopted by Island women and incorporated into various customary practices. Women on Wallis and Futuna used it to decorate the edges of mats, a technique he also witnessed in Tonga, Samoa, Noumea, and Rotuma. The use of copra sacking was also a brilliant play on his own history as a modern Islander, alluding to his experience as a copra plantation labourer and recalling the centrality of the industry in the colonial Pacific as part of a system of world markets.

If Pilioko shared the discovery of his Pacific neighbourhood with his French-Russian friend in the early 1960s, these roles were reversed when the two began a second phase of traveling and exhibiting in Europe and the Soviet Union (amongst other places) in the late 1960s. The phase began in 1967 when they took their collection to France — Michoutouchkine’s first return after fourteen years away — staging exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art in Paris, the Abbey Prémontrés in Pont-a-Mousson and the Belfort Museum in Michoutouchkine’s hometown.

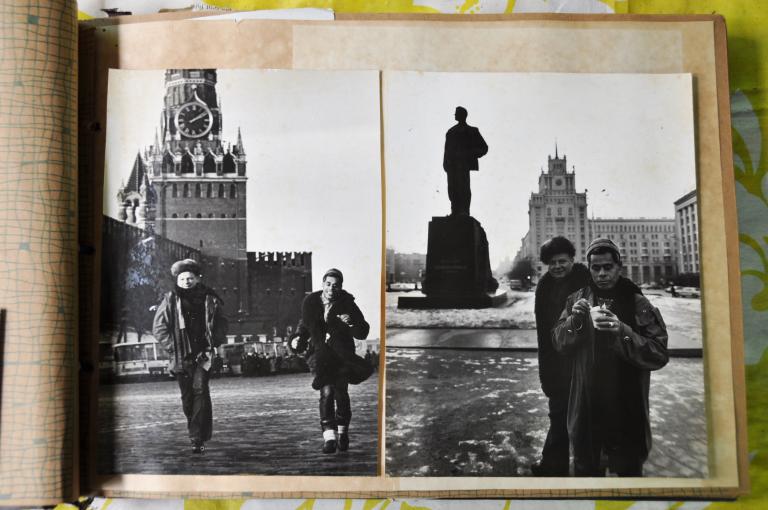

In the 1970s, they exhibited in Switzerland, Sweden, and Poland (returning at intervals to Esnaar and holding further exhibitions in the Pacific, including a multi-venue tour of Japan in 1975). Then, on the basis of relationships cultivated from periodic contacts with Russian scientific expeditions to Oceania dating back to Michoutouchkine’s first years in New Caledonia as the Governor’s secretary and translator, they were invited by the Russian Academy of Sciences to show their work and collections at multiple venues in the Soviet Union beginning in 1979 and continuing through to 1986: Moscow, Khabarovsk, Novosibirsk, Tbilisi, Erevan, Leningrad, Sardarapat (Armenia), Frunze, Samarkand, and Moscow again. [4]

There is not enough space here to account for these exhibitions in detail; what is worth noting, however, is their ultimately personal significance for Pilioko and Michoutouchkine. The fact that it was a private collection, assembled in the interval between the end of the war and the beginning of serious political decolonization in the Pacific, which is to say in a period when the region was still in the twilight of imperial rule, meant that they could stage their exhibitions with an experimental latitude unthinkable in the case of state collections.

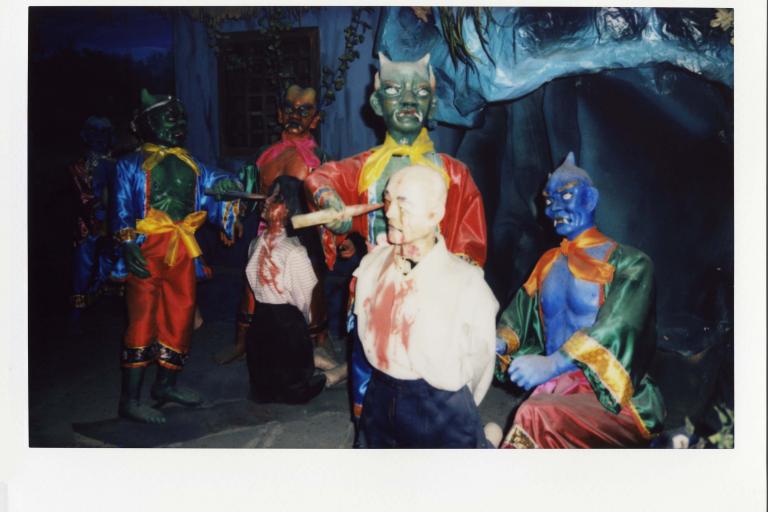

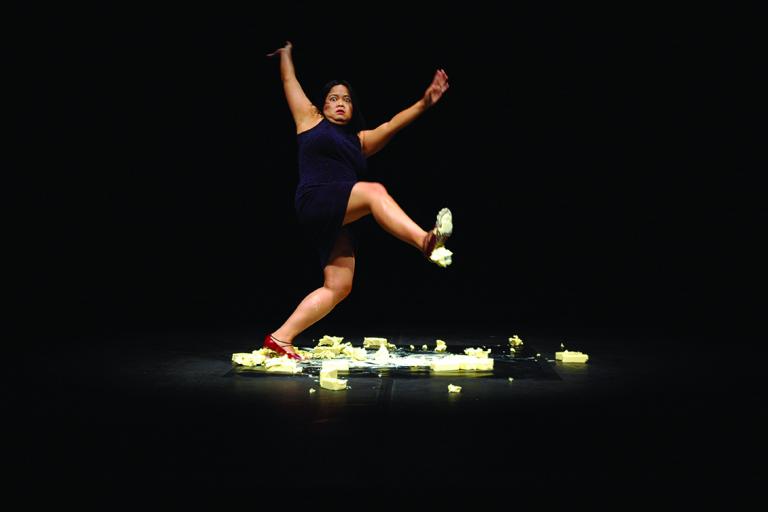

At the Museum of Modern Art in Paris, the work was part of an exhibition called Comparisons that hosted a mash-up of the “most contradictory currents” of the present. [5] The show at the Abbey Prémontrés involved work displayed outdoors in the cloisters of the ancient church; inside, Oceanic masks and figures formed the backdrop to a modern dance event with experimental choreographers, some of whom made work inspired by the collection.

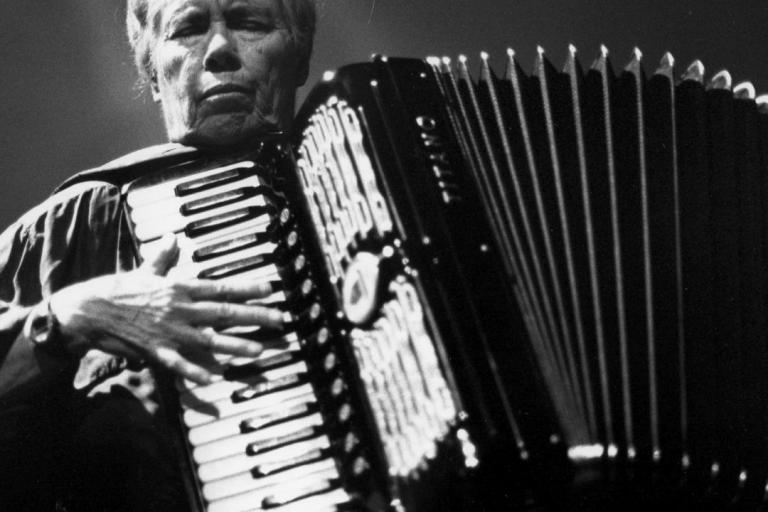

In the USSR, the collection was often displayed without the protective confinement of vitrines, and Pilioko played the slit gongs and demonstrated the use of kava bowls in a kava ceremony. The sojourns in France and elsewhere catapulted Pilioko into an international milieu of contemporary artists and exhibition opportunities that made him one of the most famous and successful Pacific artists of his generation.

For Michoutouchkine, the exhibitions were, on the one hand, remarkable feats of collaboration between himself and the international networks of personal, organizational, and political contacts required to pull them off. And from the 1970s, they were increasingly staged as quasi-official acts of international diplomacy between newly independent or autonomous Pacific nations and host nations in different parts of the world.

Yet this grand — one might even say presumptuous — ambition to exhibit Oceanic art throughout the world was, on the other hand, the counterpart of a deeply personal journey for Michoutouchkine. The exhibitions in Europe and the Soviet Union — in France and Russia in particular — were vehicles of so many “returns” for the artist.

Here he played host to his Polynesian friend, showing him his regional neighbourhood while also (re) discovering it for himself: in France, the place of his parents’ refuge from exile and his childhood formation; in Russia, the homeland of his ancestors, where he met fellow Russians and long-lost relatives, not heard from or even known about in his lifetime (in particular a half-brother and nieces from his father’s previous marriage; the message from the family had been, “if you want us to survive, do not write.” [6] ) It is a strange irony that the agent of returns should be his collection of Oceanic art — fragments scattered from the global field of contemporary villages, festivals, tribal art depots, auction houses, and chance encounters with travelers like himself.

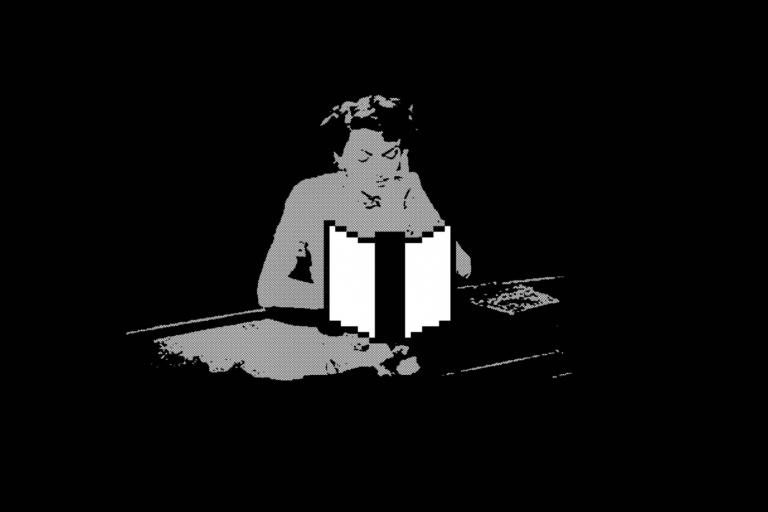

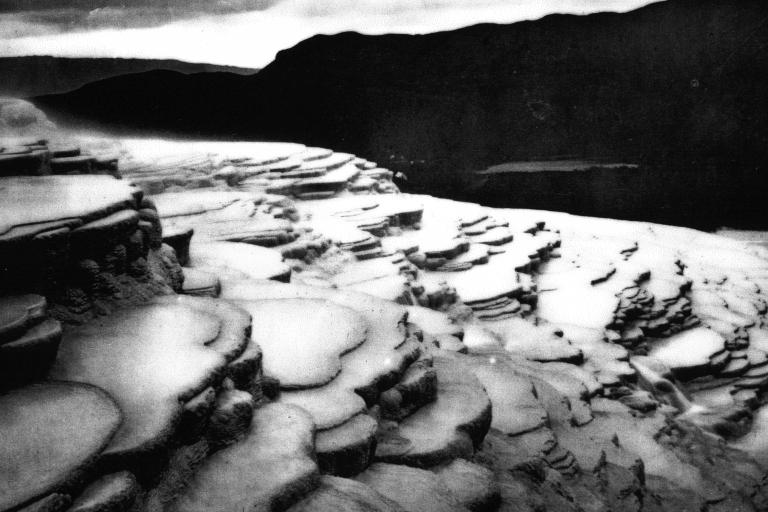

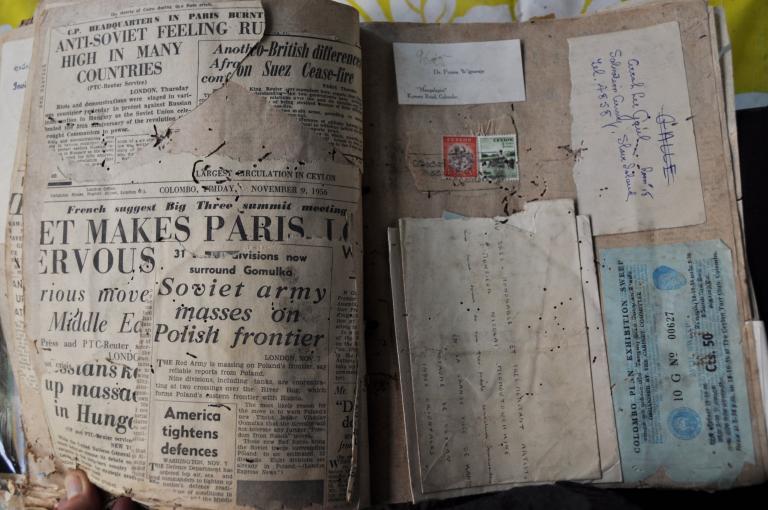

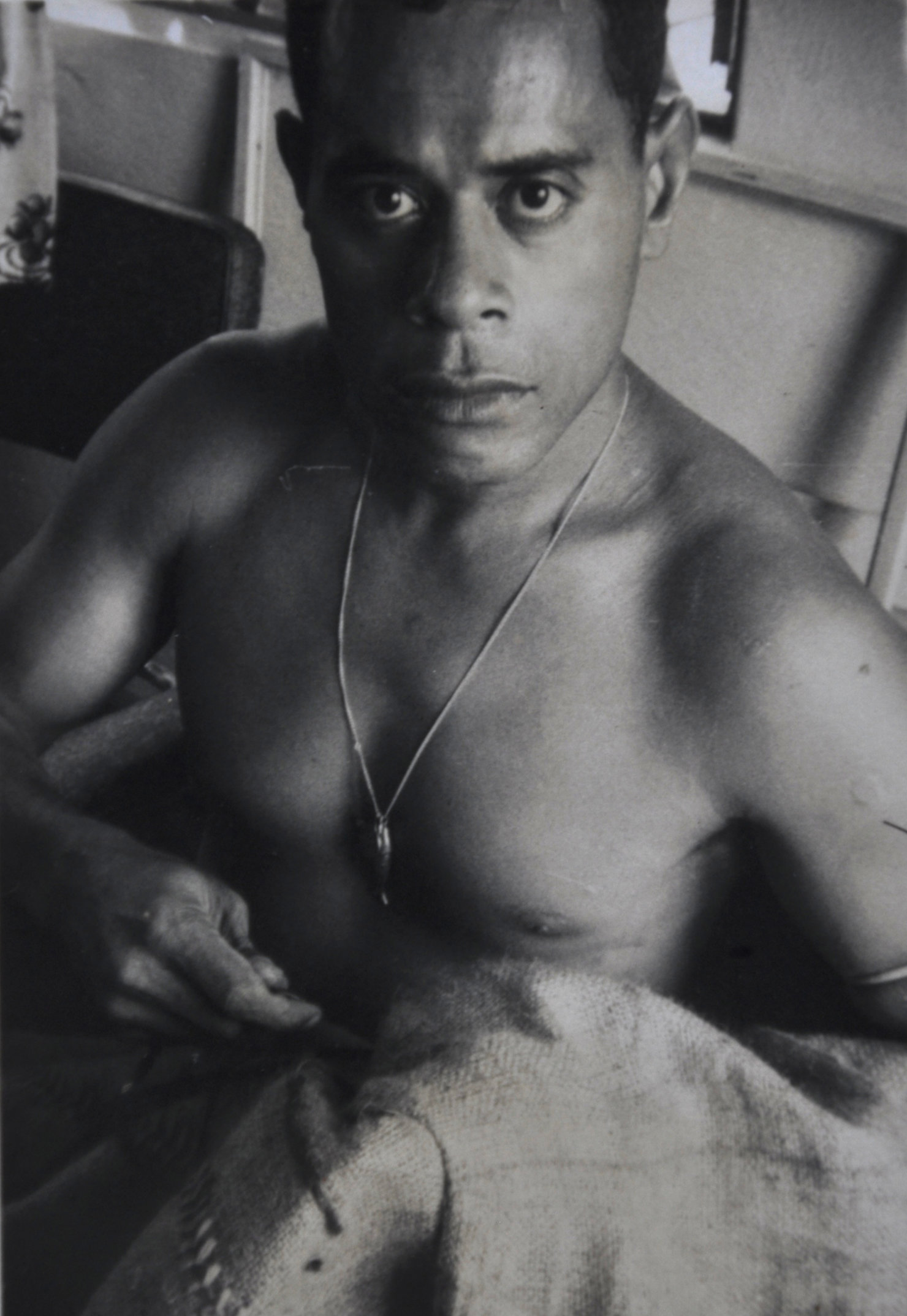

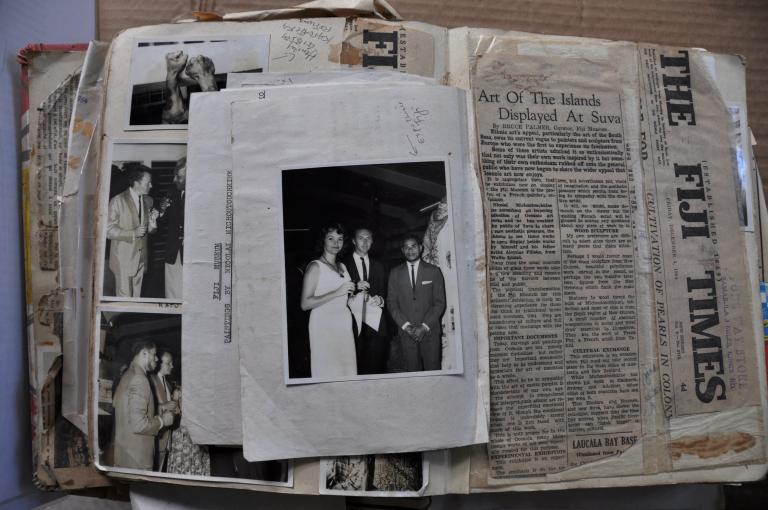

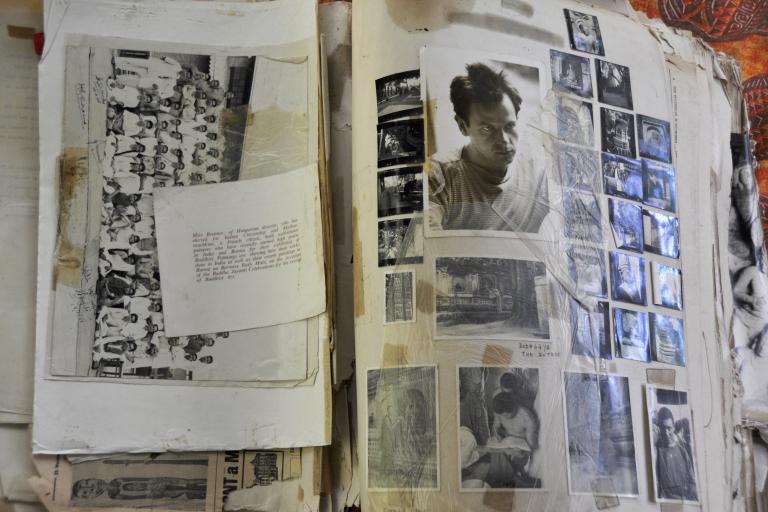

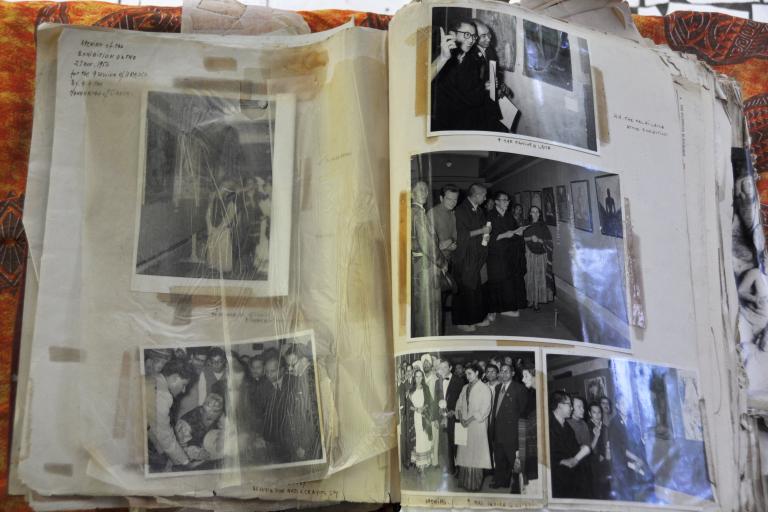

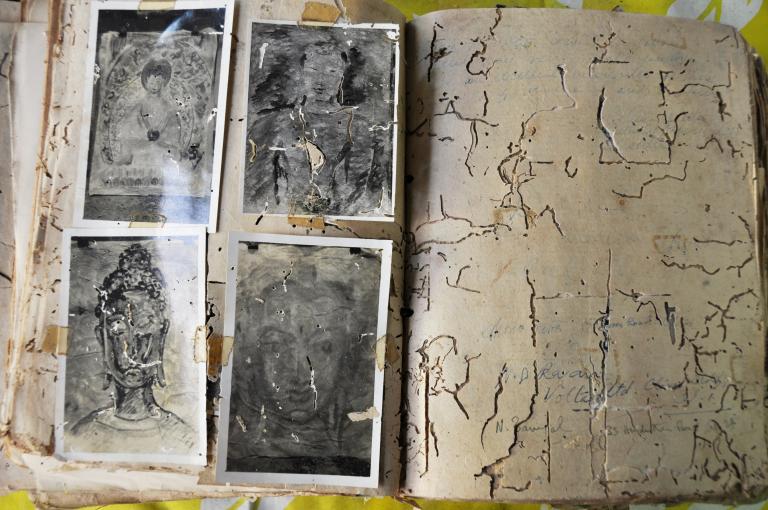

In February 2014, I revisited Esnaar with New Zealand photographer Mark Adams to document the property and photograph some of Michoutouchkine’s personal archive of scrapbooks and photo albums with the kind permission of Pilioko. A sampling of this work is reproduced here with the artist’s permission.

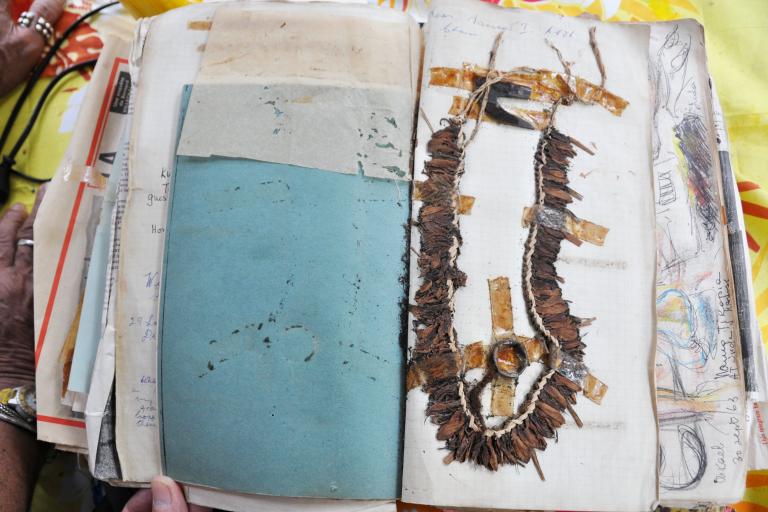

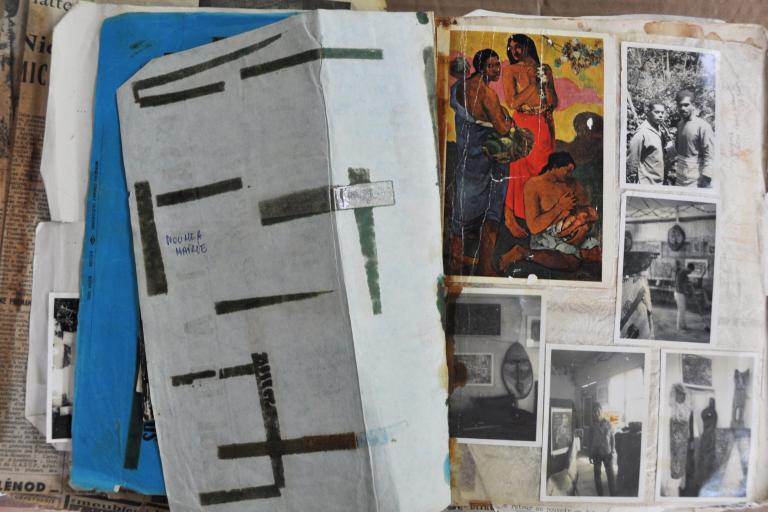

Michoutouchkine was also a self-archivist who kept photo albums and scrapbooks of their travels. Not unlike the artifact collection, the scrapbooks are diaristic “collages” assembled from various bits of traveling ephemera: name cards, travel tickets, newspaper clippings, exhibition invitations, photographs, letters, small trinkets, and so on. Many pages are also filled with autographs, written messages in various languages, and occasional drawings or paintings by friends and fleeting acquaintances.

The scrapbooks also register the political and institutional world in which he traveled. Sometimes it is distant but implicates him personally: a collage of newspaper headlines reporting the Soviet invasion of Hungary in 1956 (at a time when he was traveling in South Asia with a Hungarian expatriate by the name of Elizabeth Brunner); a leaf from a magazine of French President Charles de Gaulle visiting a cemetery of Russian war dead; a cover page of a Tahitian weekly announcing with a dramatic illustration the first nuclear bomb test at Mururoa Atoll in 1962.

For the most part, though, it reflects his association with the world of diplomats, politicians, dignitaries, museum directors, and local officials who hosted their travels and exhibitions in a context defined by the global intensification of cultures on display. As an archive, they are a far cry from the ethnographic notebooks of cultural anthropologists and colonial explorers. If Michoutouchkine and Pilioko were “modern Marco Polos,” they were not in quest of some deluded idea of the still-“primitive” or exotic, but explorers of the global habitus of post-colonial modernity.

Footnotes:

1. Marie-Claude Teissier-Landgraf, The Russian from Belfort: Thirty-Seven Years Journey by Painter Nicolaï Michoutouchkine in Oceania, Suva: Institute of Pacific Studies/University of the South Pacific, 1995, p. 2. For more on Pilioko and Michoutouchkine, see the exhibition catalogue, Nicolaï Michoutouchkine et Aloï Pilioko: 50 ans de creation en Océanie, ed. Gilbert Bladinières, Nouméa: Éditions Madrépores, 2008; Christian Coiffier, “Futuna, catalyseur de la symbiose des deux artistes: Aloï Pilioko et Nicolaï Michoutouchkine,” Le Journal de la Société des Océanistes, No. 122- 123 (2006), pp. 173-186, 173; and Aloï Pilioko, Artist of the Pacific, Suva, Fiji: Institute of Pacific Studies, University of the South Pacific, undated [c.1980]. See also my chapter, “Falling into the World: The Global Art World of Aloï Pilioko and Nicolaï Michoutouchkine,” in Mapping Modernisms: Indigeneity, Colonialism and Twentieth Century Arts, eds. Ruth B. Phillips and Elizabeth Harney, Durham NC: Duke University Press, 2019; and “Nicolaï Michoutouchkine and Aloï Pilioko: The Perpetual Travellers,” Reading Room: A Journal of Art and Culture: Elective Proximities, no. 6, 2013, pp. 86-103, from which parts of this essay have been adapted. I am also grateful to many people who have helped my research: in particular, Aloï Pilioko, Mark Adams, Max Shekleton, Kirk Huffman, Chief Jerry Taki, Lissant Bolton, Elena Govor, George Pilioko, Leonie Brunt, Pauline Charrier, Olga Suvorova, and the late Paul Gardissat.

2. Claude Levi-Strauss, “The Quest for Power,” Tristes Tropiques, trans. John and Doreen Weightman, London: Jonathan Cape Ltd., 1973 (1955), pp. 42-52, 47 and 43.

3. The partnership was romantic “only at the beginning.” A. Pilioko, personal communication, 22 January 2013.

4. Ludmilla Ivanova, “NN Mishutushkin and Exhibition: Ethnography and Art of Oceania,” Ethnographic Quarterly 2010, no. 2, pp. 97-110 (translated from the Russian for the author by Olga Suvorova, Russian Keys Ltd, Wellington, New Zealand); For more on their exhibitions in the Soviet Union, see: Ludmilla Ivanova, “Souvenirs de Russie,” in Gilbert Bladinières (ed.), op. cit., pp. 141-142; Tessier-Landgraff, op.cit., pp. 51-64; and Ethnography and the Art of Oceania, Moscow: Ministry of Culture of the USSR/Academy of Science of the USSR, 1989.

5. Exhibition notice. Michoutouchkine archive.

6. Tessier-Landgraff, op. cit., p. 616. Tessier-Landgraff, op. cit., p. 61.