It took a circuitous route for Taipei-based artist Anchi Lin (Ciwas Tahos) to begin reconnecting with her Atayal culture. The Atayal, whose roots in Taiwan stretch back thousands of years, are one of 16 officially recognized First Nations peoples on the island. Lin’s mother is Atayal, while her late father was Hō-ló, Han Taiwanese. But growing up in Taipei, Lin says her Indigenous background was rarely discussed.

“I didn’t have that kind of cultural exposure growing up,” she says. “I have a lot of Indigenous friends from my generation. A lot of them are urban Indigenous, and they face a very similar experience to what I faced growing up. They didn’t have that exposure because their parents moved to the city for reasons of survival and job opportunities.”

As a child, Lin and her parents worked together in a factory labeling and packaging bottles of alcohol sanitizer. Her parents wanted to instill in Lin a strong work ethic. She would work at the factory after school and sometimes even on weekends. “It was hard,” she says, “especially in summer as we didn’t have air conditioning. But I didn’t mind.” She laughs, “It was a way to make pocket money.”

It wasn’t until after moving to Canada that Lin realized she needed to reconnect with her Atayal roots. In 2004, Lin relocated to Vancouver and began studying Computer Science at Simon Fraser University. She says she needed a change of setting. “I think it was the moment when I came out as queer, and I was having a hard time in Taiwan. My mother thought it was a good idea that I go abroad to restructure myself, knowing that her daughter is quite different.”

Though her focus was computer science, Lin’s university required her to take some art courses. This would turn out to have a huge impact. After two years at the school, Lin decided to switch her major to art, even though it meant two additional years of study to complete her degree. At art school, Lin learned of artists such as Marina Abramović and Yoko Ono. She became interested in the body as a material and artistic medium.

But it wasn’t until after graduating in 2015 that Lin would truly begin discovering the world of Indigenous and post-colonial art. After taking an administration job at a private First Nations art gallery in Vancouver, she began reading up the work of artists including Rebecca Belmore and Dana Claxton. Lin also began talking to First Nations artists. “They were sharing their stories about their connection to their Indigeneity,” Lin says. “I was inspired as many of them came from similar situations to me.”

The artist reflected on her lack of Atayal consciousness growing up. “I started thinking, what’s going on?” she says. “Why is this Atayal identity never a highly mentioned thing? It was never highlighted or focused upon. Growing up, my parents were like, ‘Becoming financially stable is more important than talking about culture.’”

Lin determined that she would return home to Taiwan to reconnect with her Atayal culture. In 2017, after more than a decade in Canada, she moved back along with her New Zealand partner Julia. The two would marry in 2019, not long after the legalization of same-sex marriage in Taiwan. Lin is now a permanent resident of Aotearoa.

After returning to Taiwan, Lin began learning her native Squliq Atayal language, one of two major Atayal dialects. Her teacher Apang Bway, who is developing a system to help people more easily learn Squliq Atayal, runs language camps at Atayal villages in the mountains. Through attending these camps, Lin began visiting Atayal communities and speaking with elders.

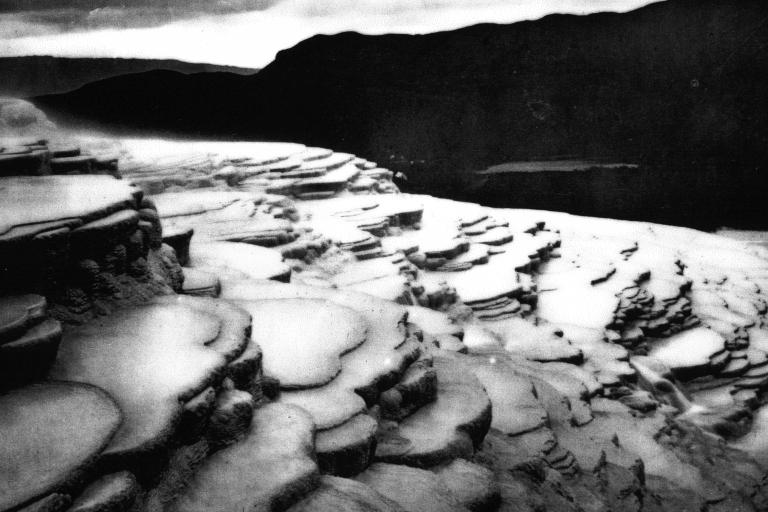

It was on a trip deep into the mountains of Nantou County on the way to Qin’ai Village that Lin had a particularly meaningful encounter. Pulling into a convenience store to grab some water, Lin struck up a conversation with an Atayal woman outside the store. The woman told her of a place called Temahahoi where only women lived but didn’t elaborate on its origins or whereabouts. That encounter sparked Lin to begin her search for Temahahoi.

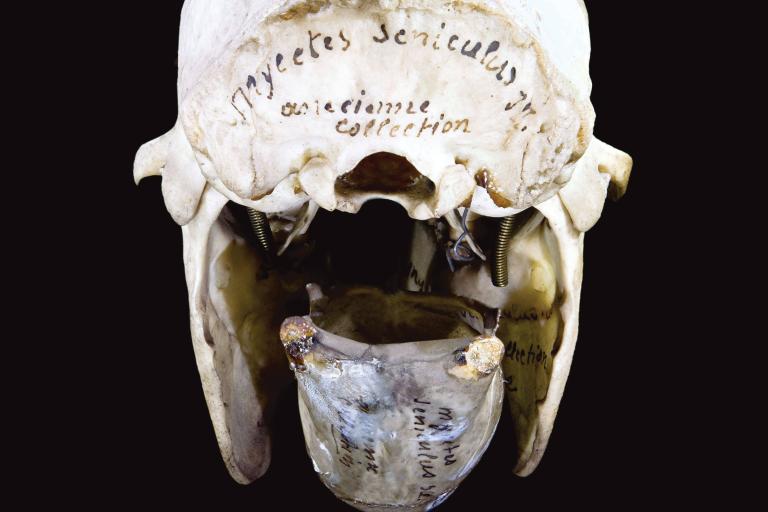

The artist found confirmation of the story in the 2017 book Heng Duan Ji by Kao Jun Hong, about mountain culture in Taiwan and the impact of Japanese colonial rule (1895-1945) on Indigenous communities. Kao had recorded the oral history of Temahahoi while conducting field research in the mountains. Lin went on to find further records of Temahahoi in other books.

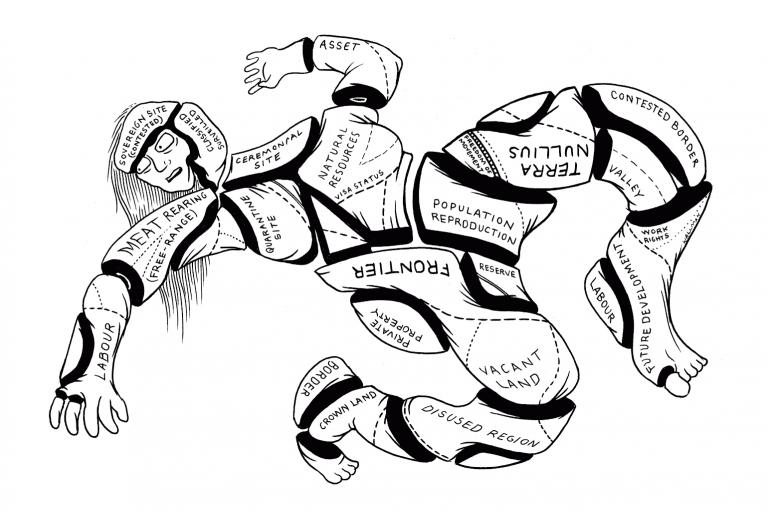

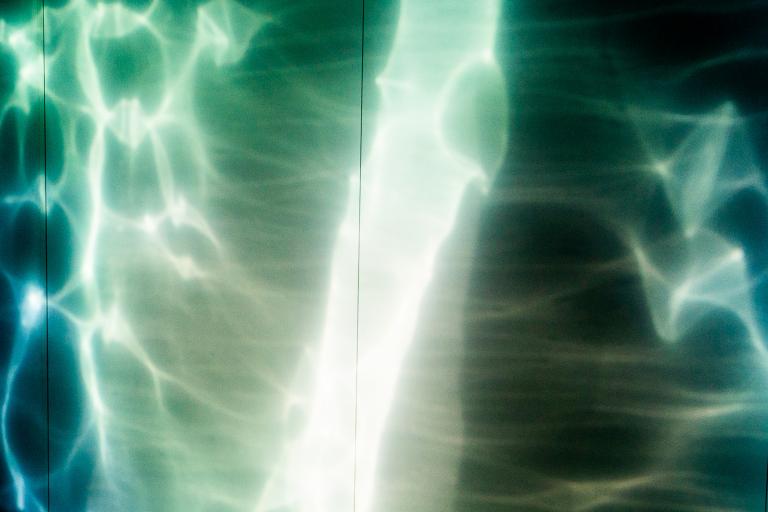

The stories tell of a community of women who lived self-sufficiently without men. Seeming to possess mystical powers, they stayed alive by inhaling smoke or steam. By lying on a sacred rock, they could become impregnated by the wind. The women were also able to communicate with bees, which protected their territory. To Lin, the Temahahoi stories sounded explicitly queer. She felt she had found a passageway into a past queer space that she wished to reactivate.

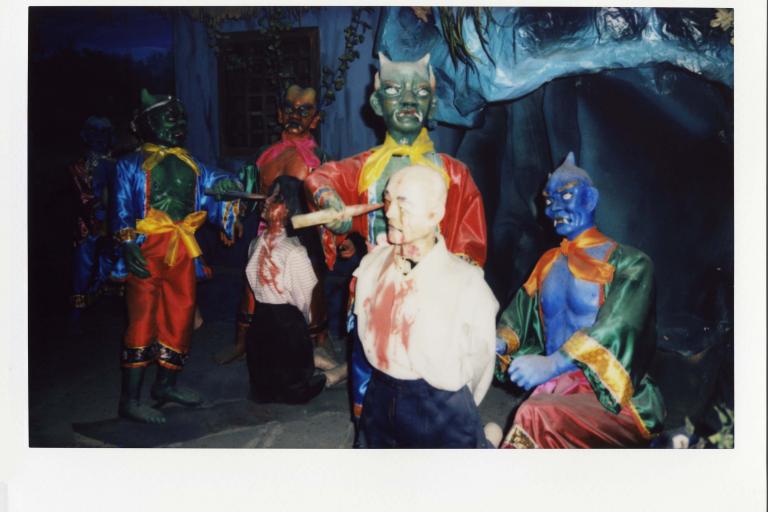

Lin began drawing on Temahahoi in her art. In her video installation “Perhaps she comes from/to__Alang”, which features in the Artspace show and was exhibited earlier by The Physics Room in Christchurch, Lin interweaves the Temahahoi stories with the tale of the brass pot from the Japanese colonial period. During that time, an oral story circulated among the Atayal that many of the tribe's women had become infertile after using a brass pot gifted to them by Japanese officials.

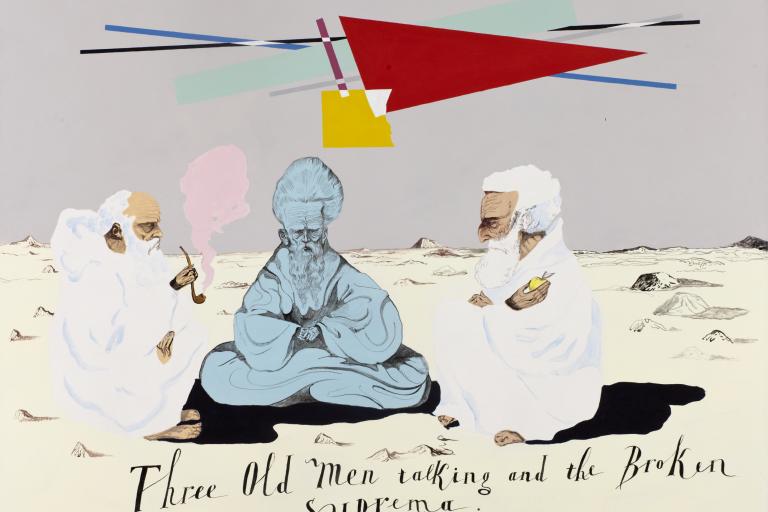

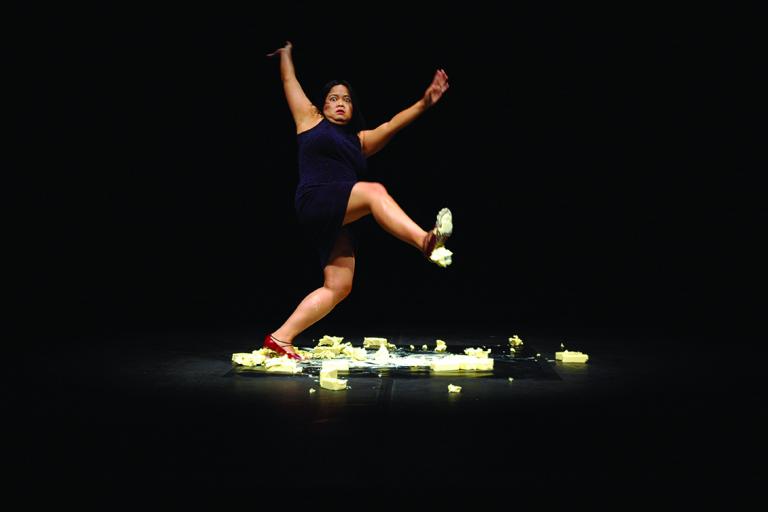

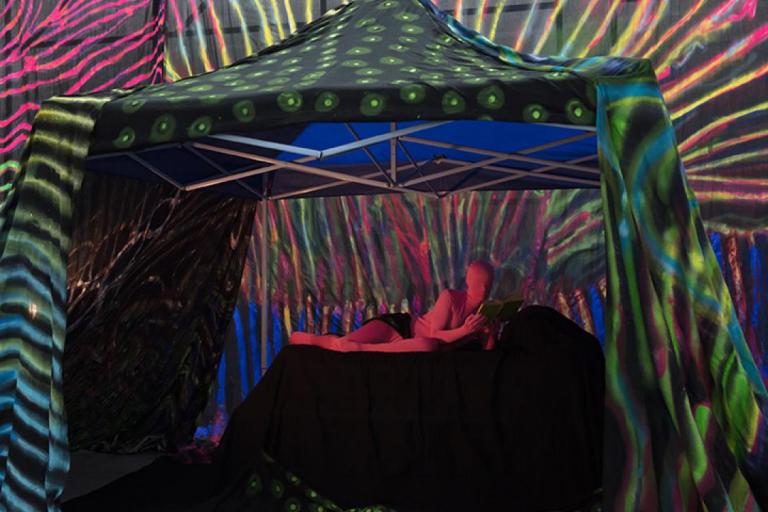

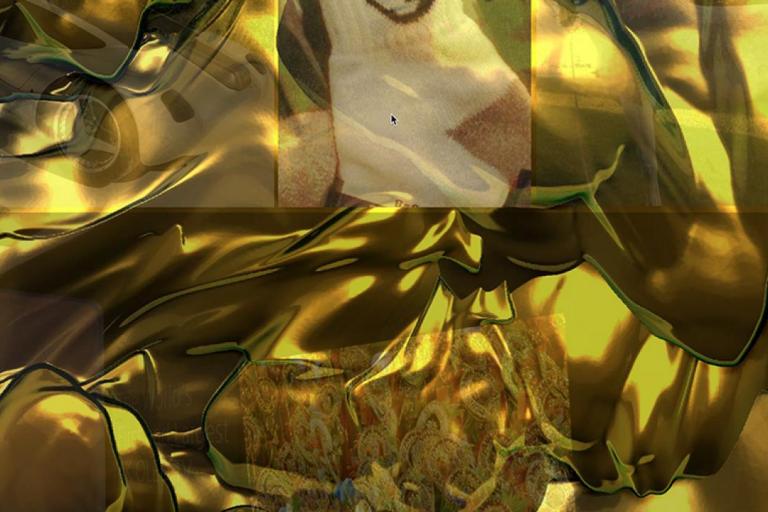

The installation shows the artist lying naked in a position similar to the Atayal funeral posture by a steaming brass pot, a jar of honey, and several stones. The artist scoops honey with a wooden spoon and drips it onto her body. She then wipes the honey off with the stones. The work extends into a 3D environment created from a scan of a black-and-red textile Lin has woven, inspired by the forests of Aowanda national park. Scattered through this virtual woodland are billboards addressing the impact of mining, the loss of bees, and the climate crisis. Later, Temahahoi women communicating in Squliq dialect worry that they can no longer be impregnated by the wind.

Lin’s new series of work, “Pswagi Temahahoi,” features a self-invented wind instrument the artist has crafted out of yellow clay. The bulbous instruments contain multiple mouthpieces intended for communal playing. Lin says she created them as way-finders to discover the location of Temahahoi. Seven of the series of 12 ocarinas were part of her 2022 solo Artspace exhibition Finding Pathways to Temahahoi in Auckland, while the others were simultaneously displayed in Germany and Indonesia as part of Documenta 15.

The new work, Lin says, is inspired by an Atayal elder who showed her how to track wild bees. “He has the ability to track wild bees through sunlight and shade,” she says. “It’s a very specific technique he learned from his father, who had learned it from his grandfather. They’re very good at tracing wild bees in the mountains. When we found the beehives, they were in these discreet spots you would have never imagined. It’s similar to how marginalized people like queer people live within the creases of society.”

Lin documented the process and made sound recordings of flying wild bees. Based upon these and those produced from the ocarinas, she created what she calls “sound scripts”. Similar to Fluxus sound notes of the 1960s, these experimental visualizations act as a record and are intended as an impetus for future queer bodies to reinterpret and recreate a collective queer space.

“Temahahoi is an Atayal oral story, Lin says. “It’s an existing queer space because queer people have long existed, so it’s not past tense. This space is still happening. I avoid the word ‘mythology’ because ‘myth’ indicates untruth. This space has always been truthful to queer people. The project is about reasserting the continuation of our existence along with nature, and nature is queer.”

This article was commissioned by Asia New Zealand Foundation.