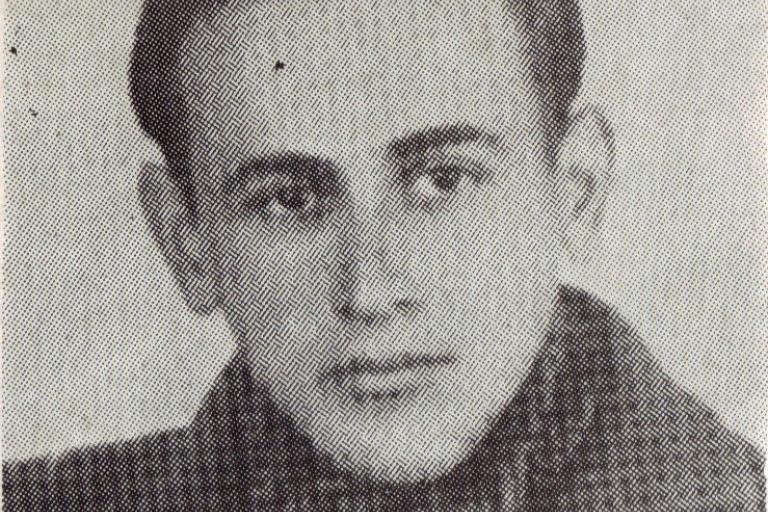

It only takes the opening sequence, composed of black waves gently moved by the morning wind and accompanied by cascades of cosmic sequencer lines, to draw everyone in completely. Mills is dressed for the occasion, sporting a suit and red tie. This, especially when contrasted with the gigantic speaker cones positioned next to him, makes him come across as much as an anachronism as his hyper-modern sonic architecture for Ruttmann’s silent era classic. His music is not the first update of Edmund Meisel’s now-lost original score, nor the first from the realms of electronic music. But he may be the first in a long line of composers to radically alter the tone of the entire movie — precise mechanical beats and psychedelic drift both complementing and counterpointing the images, adding darkness in one instant and a surprising element of humor in the next.

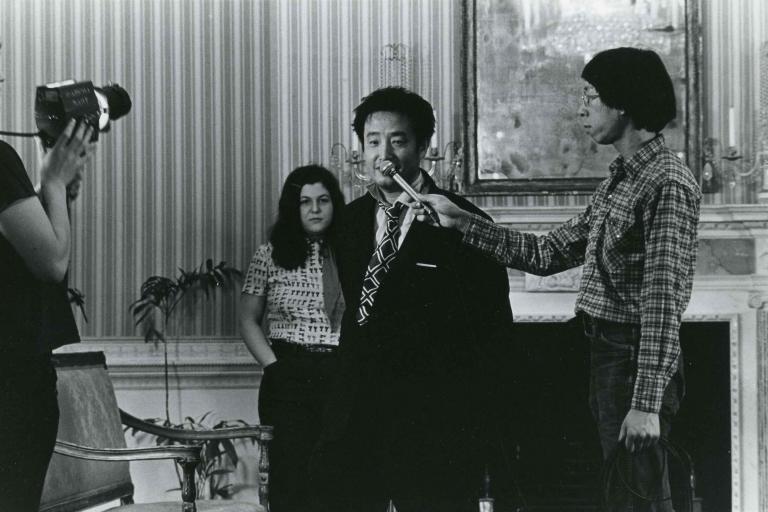

Most remarkably, Mills isn’t just reacting to the images in real-time but also mixing the score in DJ fashion, blurring the line between the once clearly delineated fields of concert and club. The approach has been a constant in his work. His first gigs as a radio presenter already involved turntables next to synthesizers, and it was one of the defining traits of his generation of Detroit producers that their productions and mixes, as his colleague Stacey Pullen put it, would be edited “like a movie house would edit their movies”. His earliest DJ stints, meanwhile, saw him transition from one record to the next at breakneck speed, his fingers rhythmically turning the pods, his hands moving faster than the speed of conscious neuronal transmission (a feat later referenced in the title of his EP The Hand Is Faster Than The Eye). In 2004, Mills laid open the foundations of his approach with the release of the DVD The Exhibitionist, a multi-angle recording of a DJ set, demonstrating both the possibilities and limits of the technology at his disposal. And yet, as much as it was intended to demystify the process of DJing, The Exhibitionist, with its art-movie setting and out-of-this-world technical prowess on display, possibly only made Mills’ unique status even more apparent.

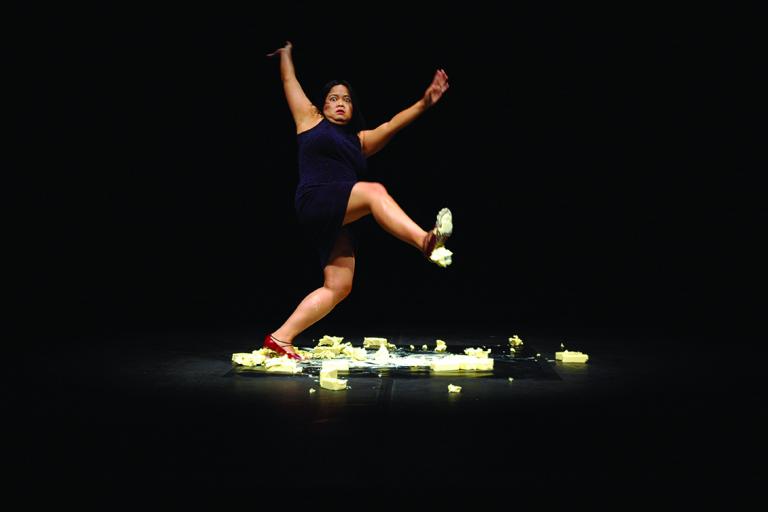

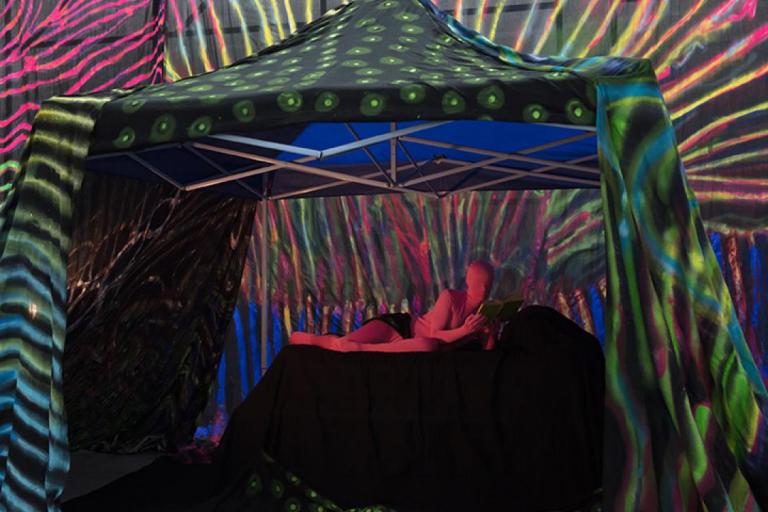

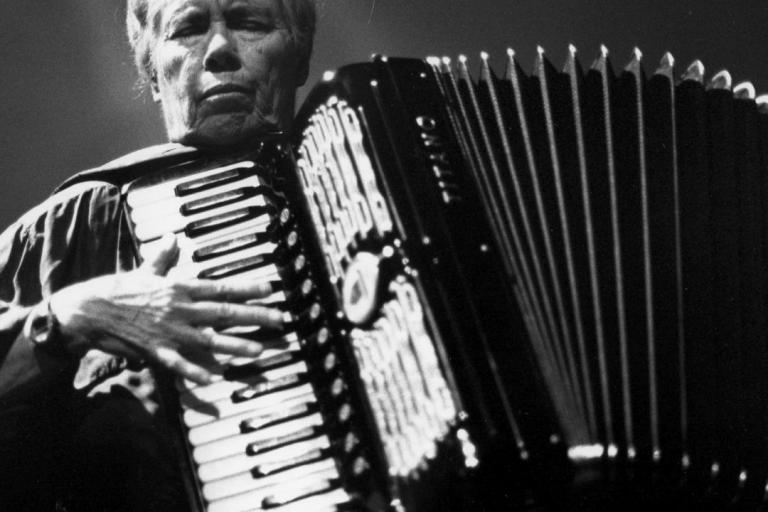

Almost exactly ten years later, Mills is back with a second installment of The Exhibitionist, this time shifting his focus away from the technology and the mechanical craft of the trade and towards the creative process and the inner considerations going on in the mind of the DJ during a performance. This shift in perspective is fitting since even the most advanced equipment has by now become all but available to everyone. The initial impact of the 2-DVD/CD set has been mixed, with its eclectic settings — involving a jam session with drummer Skeeto Valdez, a heavily processed slow-motion dance sequence, and a breathtaking 909 drum workout — leaving some viewers confused about its intents and the connection to mixing. And yet, that link is always present if one takes Mills’ personal perspective into consideration. DJing, to him, is not just defined as playing other people’s records, but as a highly fruitful performance mode, a bridge between pre-recorded sequences and improvisation; just as much as his current studio approach is vice versa inspired by the flow-states of his live sets. The Cinemax of Symphony of a Great City and The Exhibitionist 2 may seem like two entirely different projects. In many respects, however, they are made from the same cloth.

Tobias Fischer: In which way do you feel, did replacing the drums with a mixing console affect the potential of expression at your disposal?

Jeff Mills: By the time I’d turned to turntables, I’d pretty much mastered a certain type of technique in terms of playing drums. I had played percussion and drums from the second grade, all the way until high school and a little bit after — so that’s like ten years of playing in bands. I had mastered balance and rhythms, so turning to turntables was very easy. I was very even-handed and, because of playing percussion, I had the strength in my fingers and wrists. And I understood rhythm a lot, so I could listen to a rhythm and figure out how it was put together. And if you could figure out that, you could figure out how to take it apart and how things could be layered. It was a time of hip-hop and turntablism culture, so I adapted to that very, very quickly. It took just one evening to learn how to mix, and after that, I began to learn the tricks that I’d heard about that they would do in New York. And then

I practiced to the point that it became second nature. I didn’t have to look at what I was doing to know what I was doing. As a drummer, I don’t have to look at the drums before I hit them. The same thing happened with turntables.

TF: You were replacing one device for creating rhythms with another.

JM: That was very much the case — so it wasn’t just mixing. I was very much into the idea that you could use the turntable in different ways. As a drummer, you can play on the rim; you can play on the skin; you can play whatever… my approach to DJing is basically the same.

TF: Is DJing a way of playing like a band as a solo artist?

JM: Yes, I see the drum machine as the transition from a DJ set into a live performance. The drum machine can act as a record, or the impression can be that it can be like a track on vinyl. But then you have the ability to completely change it and re-write it. As a producer in the studio, I look at turntables as tracks — and I am the sync. If I have four, I can layer four things together. This is why I admire that machine and use it so much because the sound is the foundation for so many different tracks that people hear.

TF: Today, there are plenty of drummers who actually imitate drum machines. I take it that wasn’t of interest to you?

JM: (laughs) That wasn’t so attractive. I don’t think we need that. As far as I know, many producers manipulate the drum machine to make it sound like a live drummer. But it doesn’t have the imperfections. I mean, you can write these things in, but it’s not something that’s spontaneous.

TF: So it’s a difference in kind, not just in degree?

JM: Well, I’m not playing for machines. I’m a human playing for other humans, so one has to ask the question: which transcends better, things that have imperfections or things that are perfect all the time. Many people would probably disagree with me there, but I’d probably leave space open for unique things to happen. In the recording studio, I don’t use a recorder anymore. I took the multitrack recorder out. I have no other syncing mechanism except for MIDI and a little bit of CD trigger, but that’s about it. And there’s nothing to capture it except for one recorder, so I can’t play it back; I can’t redo it. The master is the master because I want to capture the moment, mistakes and all.

TF: And excitement and all?

JM: I think so. It’s not just a creation, but also the thinking and the method it took to get to that point. Ideally, I think you’re trying to put more context into the situation as much as possible. In 1992, if I could have somehow included the context or the space or the time or the day into it, if I could have included that information into the track, it would have been the ultimate track: Saturday afternoon, three o’clock, on the second floor of my apartment at this address. And if you felt that, it would be ideal.

TF: Just yesterday, I listened to one of your early mix CDs, Mix-Up Vol.2, and it has precisely this quality.

JM: It was a live recording, and it was a rough recording, which is what I wanted. We didn’t really treat it to try and make it perfect. The initial idea was to make a 3D recording. But at the time, the technology was too expensive, so I settled for just recording the audience. We set up multiple mics in the back of the room and captured the atmosphere — not so much the mix. I wanted to capture what the mix was doing to the people.

TF: Was there a point that you felt that you and the technology were truly becoming one?

JM: I had begun to go beyond the realms of turntables and the mixer as far back as 1982. Back then, I was using a drum machine and three turntables when I was the Wizard on the radio. In clubs, I used to bring drum machines. I was watching guys from Chicago, like Farley [Jackmaster Funk], and they would bring in drum machines to their parties in Detroit, so I had begun to want to go beyond that structure early on. I took to DJing really early, in the 70s. My older brother was a DJ. He had all the latest equipment, and when he stopped, he then gave it to me. I was really young and took all this stuff into my bedroom, and for hours and hours and hours, I would just practice, getting the touch, learning how to spin a record back — and all those types of things. And once I’d figured out the technique, I began to look into the music and how to manipulate it.

I was really good at manipulating time, so I made a slew of mixtapes. Almost weekly, I used to send these master mixes of what I was doing to the local radio station. No answer, no answer at all. And I gave up on it. To make a long story short, one of the main stations changed its programming director. Someone from New York came into Detroit and replaced the guy. And this guy was from WBLS, the same station as Red Alert. He knew what hip-hop was and what scratching was. When he opened up his cabinet to clean it out, all these tapes fell out, so he picked up the tapes and put one in, and it was one of my mixes. And it gave him the idea that he could have the same thing he used to have in New York — so he contacted me and asked if I could come in for an audition.

TF: On The Exhibitionist 2, there are many different performance situations. Would you say the thinking process is essentially the same for all of them?

JM: The objective is the same, that’s for sure. But with every new thing that I try, I learn ten new things. And some of those things apply to the next idea. There’s a certain amount of awareness, knowing that if I bring a live drummer in and we don’t rehearse but just do it, something interesting is going to come up. We both know what we’re doing on our instruments. Something unique is going to happen, and the camera is going to capture that.

TF: Would you say the idea is always more important than the tools you’re using?

JM: Definitely. Actually, the idea trumps the result as far as I’m concerned. Sometimes it’s even more interesting to just have the idea and not materialize it. In fact, I have done that for certain releases and concepts. I will draw everything out, mix sketches and never release them. Cycle 30, a release I made in the mid-90s, was one of those things. I almost didn’t release it. I convinced myself that the concept was so justified and had such a purpose that I was really ready to move on to something else. I didn’t care if people realized it. Purpose Maker is another thing. I wasn’t planning on releasing those tracks to the public.

TF: Is music a form of communication, a language?

JM: Yes, but it’s one-way, though, not two-way. One-way is actually better, I believe. Projecting a certain idea without the expectation that you’ll ever receive an answer — I think that’s probably the best way to create.

TF: Because the idea comes across more clearly?

JM: Because you don’t expect anything from anyone. You are content only with what you believe is your purpose.

TF: So you present the idea…

JM: You present the idea, and that’s it. That, to me, is the best way. It’s near impossible, and I don’t think anyone has ever succeeded in doing it (laughs). But it’s a goal — to only project ideas.

TF: I suppose the problem is that, as social beings, we always take in things from what surrounds us. And they influence us.

JM: Sometimes, yes. But to be honest, more and more, I’m not paying attention to the audience I’m playing for because I can use more of my imagination to help shape the DJ set. Like the same way as when I’m in the studio — I don’t have an audience there, so I have to imagine places and different scenarios. When I have 2,000 people in front of me, I don’t really see them, even if I’m looking at them. My mind is somewhere else, and I’m using the music to translate that. And those DJ sets tend to be the most interesting, where I have the impression that I’ve taken them somewhere. And that can only happen if I’m not looking at them to see what they would like to have.

TF: You’re giving them something they didn’t know they wanted.

JM: Well… I used to think that, too, but now I don’t care. I realized that what the people want is something special — and I can’t give them that if I’m looking at them and I can see they want me to do something special. I need to be cut off visually from them somehow in order to think things in my own self and imagine things in my own self, even though they’re in front of me — just try to be as creative as I can with the music that I have and make something that they would remember. I know it would be politically correct to say that I would like to become one with my audience. But I have a different approach to that. I’ve found too many examples where the audience becomes an obstacle. They get in the way of the creative process.

TF: Musically and technically speaking, your presence is no longer required in the club. You could be DJing in another room.

JM: I’ve done that. I’ve done examples where I’m not even in the same room.

TF: Was that satisfying?

JM: Actually, it was quite interesting. It was in Tokyo. I was in another part of the building — it was a skyscraper. And we made the case that I was conceptually on another planet, and I would send my signal back. They never saw me, I never went to the room. I just had a small screen of the audience and that’s it. After the set was over, I went through another door, got into a cab and went back to the hotel (laughs). And because of that, I felt that I could do anything. If I stopped the music, I didn’t know if they, too, stopped or not, and if so, I didn’t know what their reaction was, so I could only imagine these people. I could hear them, because it was about 1,000 people and they weren’t that far away from me, but I had no idea what they were doing.

TF: You mentioned that there were situations, especially in the beginning of your career, where you would be spinning faster than you could consciously follow. Who or what was in control in these situations, would you say?

JM: It wasn’t me. When that happens, no one’s in control. There are cases where I’ll come up with an idea and the idea leads nowhere. And I don’t know what I’m going to do next, and I don’t know how much time I have to come up with an idea and I’m stuck.

TF: Do you nonetheless prefer these unstable situations?

JM: I think so, yes. It keeps it interesting. The more of those situations you have, the better it makes you at problem-solving. That was until the Pioneer CDJ-200 made a loop button that you could just press and then your time is suspended. That made it a little bit too easy. But before, you would not only have to know what you were going to play, but also where you were in terms of time, and how much time you have, and when the break’s coming in. And I need to find a record quickly before the break comes in 16 bars. So DJs were great keepers of time and measurement. And I don’t know how many other DJs would say this, but that actually carries over into other parts of your life which have nothing to do with music. You become a great manager of time. Your timing becomes better at everything, really. We spend all our lives making decisions for other people. And we are always weighing what is the best thing to do for a crowd of 1,000 people. And you begin to think more for people and more for the situation. You’re considering the context and everything around it. You become more thoughtful. It changes your personality. You become less narrow-minded and more open — not just to music, but literally to everything. You learn to look at things from many different perspectives.

TF: So what exactly is the goal of one of your DJ sets?

JM: I went through two stages. First, when I started, it was about the audience. And then it became more about what I want. Now, it’s about “it”. I think more about “it”, I care more about “it” than the people or myself. And that seems to supersede the players of the situation. Getting people to dance to what I’m creating is enhancing “it”. And by “it” I probably mean the culture and the artform of electronic music. If they have a great time, their energy carries over to other people and makes them realize it’s a good thing for me to be here at this time at this moment — which brings things back to the original idea of music bringing people together. That was one of the reasons they wanted to kill disco music in the US. It has that effect to lessen the lines between people. It creates a common thread that ties everyone together. The atmosphere is more open, and people can be more free and more the person they would really like to become for those few hours. And then they begin to see the world differently.

TF: Speaking about these difficult situations you mentioned earlier, you once said you were more open towards errors. What constitutes an error from your perspective?

JM: When something happens that I didn’t plan to happen (laughs).

TF: Because sometimes your transitions initially don’t seem that smooth. But then you listen back to them and they seem to make perfect sense.

JM: You have to see that I wasn’t taught to DJ for that. That idea that a DJ should make a perfect mix didn’t come until the late 80s. Until then, the focus of a mix wasn’t on how perfect it was — it was on what the effect of it was. The guy played this record and then he played that record, and it made the transition, and it took the party somewhere else. That was really the focus. From a European perspective, this obsession with perfection didn’t really come until the late 80s, early 90s. Before that, the objective was to take the people somewhere higher by connecting a record you knew to something else they weren’t listening to. I still don’t have that much of an interest in making mixes that are perfect. Because if I do that, what’s the difference between what I do and what someone else does? You can’t feel that it’s me. So I actually favour the idea that the mixing has the character of the person who’s doing it.

TF: I have this suspicion that the ideal of perfection became dominant when artists started committing mixes to CD…

JM: Yes, and DJs felt that it had to be flawless because people started listening closely. I still disagree with that. If we want perfect mixes, then we should just get a machine to do it — which we have (laughs). After all, if the machine is so perfect, what would you need people for? You don’t need someone like me.

TF: So if there were a robot who could take absolutely everything into consideration — the audience, the mixing, the venue… Would it be a better mix?

JM: It would, and I’d be out of my job.

TF: Meanwhile, you’ve proposed the intriguing idea of a Jeff Mills software…

JM: It was an idea that I had, but again, the technology wasn’t there then. This was in the late 90s. What I wanted to do was to modify a mixer for MIDI so that all the settings on the mixer could be recorded; it could record my habits, what I normally do as a DJ. And then that program could be put on any kind of music — it could record the time it would take for me to put something up and then analyze how that could be applied to hip-hop or any other style of music. Now that’s possible, but I don’t think so much of the idea. But that idea has grown more into a virtual reality type of thing: trying to capture what it feels like to be a DJ so that the viewer could have all those perspectives. So basically, it would allow you to feel as though you’re in that position without you having to be a DJ. That’s when we take the giant step forward. It is hot, so I roll my sleeves up, and you would feel that. Or the record’s about to run out, so I get tense. If we can translate all these ideas, you begin to understand what it feels like to mix.

TF: There are a few instances in the first Exhibitionist where you put a record on the turntable, then reconsider and put a different one on. I’m just wondering why you realize this after putting it on the turntable. Does the option become more real in a way?

JM: It means I grabbed it, convinced that it’s the one, then I put it on and know it doesn’t work. And I guess that used to happen more than now. Because of the way DJs mix today, they know what they’re going to play next more than we used to back then.

TF: Why is that, do you think?

JM: I guess it’s the way music is kept. I think most DJs don’t sort it out in the moment. I think they already have it in their mind what goes good with what, maybe because they’ve done it before, and they don’t mix up their music. Everything is programmed in a way that’s very easy to see. Because, when I used vinyl, I would just put the things in the case and go — I wouldn’t open it until I got to the next party, so I wouldn’t know where’s what. It’s literally a mixed-up library of music, so for every record I want, I have to search through the whole thing. And in that process, I find something that’s an even better idea. It’s the same with CDs. I use them, but I don’t put a lot of information on them, so I really don’t know what most of the CDs are. And then I put it in, and I hear it, and it’s just not the right thing.

TF: You once said that you were looking for sounds that emit very intense emotions. That’s an interesting thought since I would expect the emotion not to be in the sound but in the listener. Do you feel certain sounds actually have a distinct emotional quality of their own?

JM: Oh yes, of course. It seems to work better when there’s an intent when there’s a motive to use this sound to demonstrate something or to translate something big or heavy or spacious. To do it in a conceptual way is, I think when it has the most effect. And it is those instances that have the ability to change a setting or allow the setting to take a turn. When I’m in the studio, and I’m making something that I think will explode, chances are that people understand that in the same way. That’s why I think that things that have an idea are more convincing than things that happen by chance. If you have a strategy of what you’re doing, why you’re making music, what you are making music towards, you will probably become better at making music that is more meaningful and more valuable for people. If we just mix something as a second thought, it works but won’t be as effective.

TF: What kind of sounds are particularly effective at bringing out these changes that you speak of?

JM: Clustered sounds are good — things that aren’t so clear; things that have multiple chord arrangements, so that every time you listen to it, you hear something else; or the sound of something only hitting once — not twice — so you’d have a certain amount of silence before it and a certain amount of silence after it. And that must be recorded into the recording or whatever it is. And the listener will put more value to that one sound than eight of them. They’ll listen to it differently. If I were to go to a party tonight and I were to play just one sound at the machine and then walk off stage, they’d think I’m nuts.

TF: It would be a very powerful performance, though.

JM: It would be (laughs).