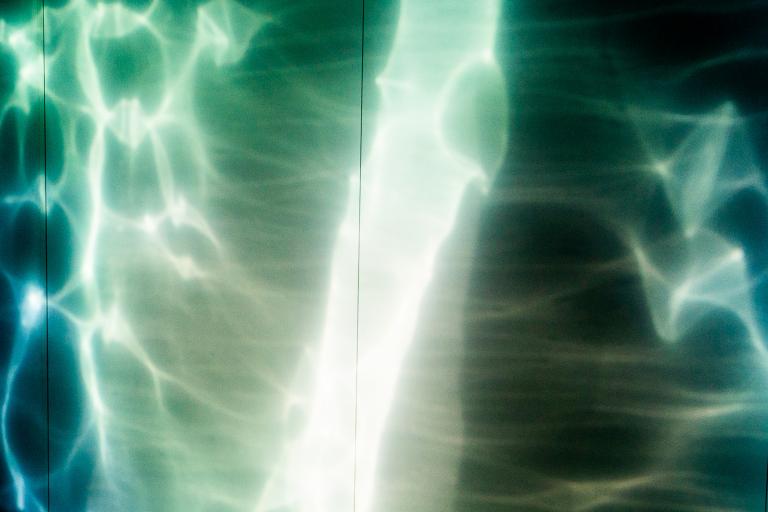

On their 1990 release, Troglodyte's Delight, Pauline Oliveros, and the Deep Listening Band didn't just use water as a backdrop or compositional element. Instead, they treated it as an additional instrumentalist within the ensemble's line-up. There were solos for water, feedback mechanisms between humans and H2O, liquid following human guidance, and liquid acting as a leader. The entire performance took place on a canvas constantly filled with droplets, rain, or the babbling of a stream. Other albums may have garnered more attention or praise in Oliveros' career. But Troglodyte's Delight can be said to constitute her most representative and demonstrative effort, communicating the depth of her philosophy as well as her entirely natural approach to collaboration. There was something playful and rebellious about the record too. It didn't sternly question the borders of music — it outright ignored them. And it may well have been dreamt up decades earlier, in the head of a nine-year-old girl, exploring the world around her through sound.

* * *

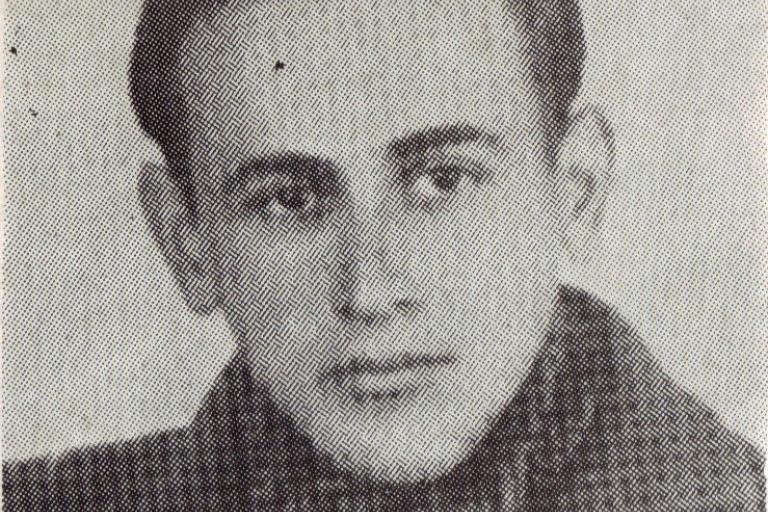

It was a childhood coloured in a multitude of timbres. Her mother and grandmother were both piano teachers, and there'd be music in the house all day. Oliveros could hear the pieces played by their students, percolating through closed doors and filtered by empty hallways, mysterious ghost études played by invisible fingers far away. In her experience, the context of the sounds was as important as the actual composition. One of her greatest treasures was an old Victrola gramophone, on which a wild array of music would be played — marching band marches, classical symphonies, folk, and jazz — segueing in and out of each other as though being part of an eclectic 1930s DJ-set. When the Victrola ran down, the music would droop, causing tiny spasms of delight. Oliveros also loved her father's shortwave radio, its curious hiss, and plops, which sounded like mysterious utterances, like an alien form of electronic speech. And yet, music wasn't restricted to the house. Outside, a whole world of acoustic impressions was waiting to be discovered, explored, and experienced. There were the insects, their fine hums, rasping buzzes, and piercing metallic crackle, as well as the deep, dynamic stereophonic fields of the cicadas. There were all kinds of animals too, birds and most of all frogs, their croaking loud and clear in the cool morning air. There was an inexhaustible multitude of sounds, and there were never any borders between them. Her favourite musicians were the foley people from the radio plays, who imitated natural sounds with their hands, mouth, or found objects. [1]

* * *

Oliveros didn't choose the accordion on an impulse, and there was no magical moment of fate that led her to embrace the instrument. As a child, she would play anything from the drums to the tuba to a French horn and could literally have excelled in any of them. It was her mother who'd bought her an accordion when she was nine, a present and a business investment at the same time. What today is considered an exotic instrument was really a widely popular one in the 1940s. The gift would eventually turn into a fascination, but it was always the social aspect of music that interested Oliveros far more than honing her technique. Later, she would create feedback mechanisms, allowing her to play her lines back to herself to initiate an inner and outer dialogue, surprise her, and take the music to unexpected shores. As simple as the approach might have been, there was something philosophical to it as well. What she was playing right now would, when played back, turn into the future, time folding back into itself, the current moment stretched into infinity.

* * *

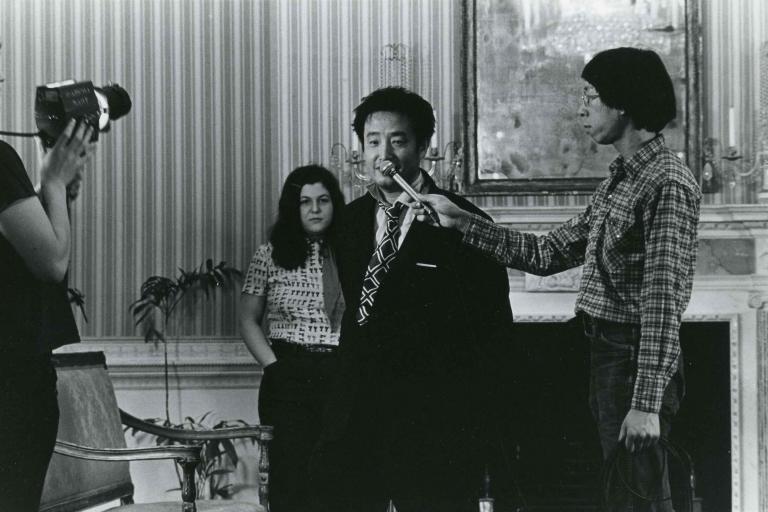

I arrived in California in 1952. I had my accordion and $300. I supported myself with a day job for about nine months, and then I began to get a string of accordion students. I went back to school at San Francisco State, where I met Terry Riley, Loren Rush, and Stuart Dempster (...) I didn't know anyone, and I had to make my own way. I began to play my accordion at casual engagements. Eventually, through going to school at San Francisco State College, I met Robert Erickson, who became my mentor and teacher for six or seven years. I became connected with a kind of group of people who were interested in new music. This eventually led to the founding of the San Francisco Tape Music Center with Morton Subotnick and Ramon Sender, which was transferred after several years to Mills College and became the Center for Contemporary Music. It is still there as that today. [2]

* * *

San Francisco proved to be a fruitful place for Oliveros. The Tape Music Center would turn into a stem cell of a whole generation of American experimental sound artists. Her own work was being performed, garnering attention and slowly building an audience. She defined her areas of interest, gave into the mysterious attraction of La Monte Young's compositions, the beauty that lay in the galaxies opened up by a single tone. Despite its name, the Tape Music Center was not a high-tech institution, and a lot of Oliveros' music was created using exceedingly simple tools. One of her compositions from that period, for example, was called "Apple Box" and made use of the resonant body of the title — giving its amplification. In the sixties, there'd even be a fully-fledged apple box orchestra performance, realized with a multi-channel mixing board. She built it for the occasion, handicraft turning into an essential part of the job:

When I made my first tape piece, I had no circuits, filters, modulation, or anything else. So I used a mike in the bathtub for reverb; I used cardboard tubes as resonators, as resonating filters. I would sing or talk or play through the tubes. I used the walls to amplify little sounds and record them, and I had a Silvertone tape recorder from Sears Roebuck, which for some reason or other would allow you to hand-wind the tape in record mode; it was like a variable speed recorder. That's how I did my early work. It was not with any of the things you buy off the shelf today. [3]

* * *

Carl Stone: Did composers at that time (...) have a (...) feeling of commonality or purpose, or was it very competitive and individual?

Pauline Oliveros: I think there were cooperative feelings. (...) There was a division which was represented by the Schoenberg-Stravinsky polarity. I remember that was one of the things that were thrown at me often, that particular polarity. And my music seemed to be representative of the Schoenberg side at the time, except I was never a twelve-tone composer. I mean, I never used any theory or techniques at all. [4]

* * *

One day, Oliveros was recording the traffic noises outside her apartment. When she listened back to the sounds from the street, she noticed that they appeared to bear no resemblance to her initial impressions. Clearly, one could appreciate very different things within an identical scenario, depending on whether one was listening to isolated events or the entire field and spectrum of sounds and patterns. Intrigued by the phenomenon, she developed a technique to more fully understand and grasp these differences. As with any term, 'deep listening', as it would come to be called, would be prone to misunderstandings. Deep listening is not just a process; it is a practice. It is not just about how we perceive sounds, but about how many we perceive and where we direct our focus. More importantly, however, it would not remain a personal revelation but open itself up to the world, with thousands of musicians studying it. The discovery would turn into a pivotal moment and mark the beginning of her own path in music. "One can listen to anything anytime and perceive it as music if you are listening that way. So one way to approach this is simply to be open and ready to listen no matter where you are. So it may be more a question of how to listen rather than what to select." [5]

* * *

Around 1969, The New York Times contacted me and wanted to know if I wanted to write about anything. They didn't give me a subject. I said, "Sure!" And then I came up with 'And Don't Call Them Lady Composers'. Part of that was that I had been to New York several times by that year, and Morton Feldman wanted to introduce me to composers at Max Polikov's house - they used to gather there and hang out. So I went to a gathering, and Morty introduced me as "the world's most famous lady composer". I had to take exception to that. I told Morty that was not exactly how I wanted to be introduced because it marginalized me immediately. I just wanted to be introduced as a composer. I think that experience and probably many other experiences of the sort caused me to use that title and to start to point out how imbalanced everything was and how hard it was for women to be taken seriously as creators of music. [6]

* * *

In the seventies, Oliveros chose to follow up on her interest in social topics in music and the idea of interaction and intuition as important issues. Her 'Sonic Meditations' were exercises in group collaboration, guided by little more than very brief instructions at the beginning of a session. These instructions could, for example, read as follows:

Sustain a tone or sound until any desire to change it disappears. When there is no longer any desire to change the tone or sound, then change it. [7]

In 1980, a performance at the Guggenheim museum asked 100 participants to tune to each other, resulting in "an unpredictable but fascinating gradual shift in harmony, as groups of singers slowly gravitated towards particular pitches". [8]

My interest is making it possible for anyone to participate in musical creativity spontaneously. My Sonic Meditations were composed as ways for anyone to experience sound-making without musical training. It is a way of reflecting back on the natural musical sensitivities that people are born with and empowering them to create something together. At the least, there is a realization that there is a possibility. [9]

Q: You once said: "I feel that listening is the basis of creativity and culture. How you're listening is how you develop a culture and how a community of people listens is what creates their culture." Why is that?

A: We hear with our ears 24/7. Our ears transduce the waveforms into electrical energy that is transmitted to the brain. The brain is listening. Listening is reflexive and a mysterious process — mysterious because the process is not necessarily understood. How we listen depends on our memory and accumulation of experiences, emotional reactions, feelings, and thinking. The quality of listening then depends on experiential education. There are, of course, many differences in the ways of listening. In order to understand how someone else listens, the experience has to be described in some way. As experiences are shared, a community of interest may develop. When the interest is strong, it may become a part of a culture or even the basis for a culture. This happens, of course, with musicians. So a culture can grow around a particular musical style and be conserved. When the charge goes out of a style, then an innovation may occur that starts a new culture. Thus we have many different styles and cultures. [10]

* * *

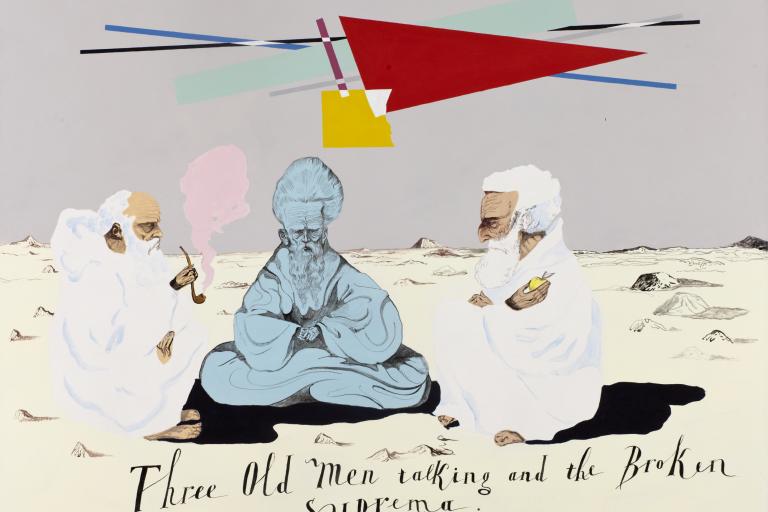

The Wanderer, composed in 1982 and originally released in 1984, sees Oliveros as a performer, improviser, and builder of overtone-rich soundscapes and composer of colourful and energetic orchestral music. Oliveros had come a long way and found her own take on the drone. To her, it was not so much a static construct or a metaphor for complete calm.

Rather, it was a tool for staying in the stream, of defining the act of composition as sculpting a succession of moments, with time rather than intellectual concepts creating a bond between them. The Wanderer's 15-minute "Horse Sings from Cloud" floats through shifting chord structures and moments of light-flooded meadows as well as a few slightly claustrophobic passages, in which closely-spaced tones narrow the acoustic space. Sometimes these extremes lie within the distance of a single breath or segue into one another by moving a single note a semi-step up or downwards. Even more revealingly, the title track, a spirited and sweeping take on minimalism propelled by combustible rhythmical cells and performed in conjunction with the Springfield Accordion Orchestra, flows from a solemn, meditative opening section — the drone is a pool of potentiality here, a moment of reflection, from which literally anything could flow.

* * *

In 1988, Oliveros teams up with Stuart Dempster and Panaiotis, and together they drive to Fort Worden. Their baggage: A trombone, Oliveros' accordion, and a didgeridoo. Their destination: A now-empty water cistern, where they intend to engage in a spontaneous jam session. The trio set up their gear, and inside the cistern, they miraculously find large and small pipes and metal pieces, which they decide to use as instruments. The moment they play their first note, they know they have arrived at the right spot. The Ft. Worden Cistern at the Olympic Peninsula, which they will later dub the "Cistern Chapel", is a vast, mysterious and cavernous space with a majestic delay. The natural resonance of the place will guide their interaction, as bright accordion reverb lingers in the air like a fine spray or a single didgeridoo tone seems to perpetuate into infinity – a feat acknowledged on the resulting album (The Ready Made Boomerang) by tuning the length of the opening track to the cistern's forty-five second reverberation time. The trio spends two days and a total of five hours on location, experimenting with different set-ups and two recording engineers. It isn't the only cistern-recording in Oliveros' discography; she had already documented a solo session in a Cologne cistern in 1984. But the magic of the Fort Worden sessions will remain unparalleled.

* * *

This listening we are talking about is a kind of communion, but if we are not mindful, listening can, like anything else, become a form of consumption.

In this country, music is generally thought of as entertainment, not as a vehicle for social change or the expansion of one's consciousness(...) I feel it is important for people to make their own music ...

Music need not be the domain of specialists. After all, the 'musician' must also eat, sleep, shit, make love and ask more questions(...) [11]

Q: Today, it occasionally seems as though more people are producing music in one way or another than ever but are finding increasingly less time to actually listen to someone else's.

A: There is certainly more music-making these days than fifty years ago. Partly this is because there are far more people in the world now and there are more ways for people to make music and also to listen to music. I find that I have little time to listen to my own music except when I am performing it. With the number of recordings that come to me, I could spend the rest of my life just listening to those. So yes, there seems to be more output than there is time to take in. This need not be a problem unless it is taken as a problem. It is healthy to make music. [12]

* * *

In the late 1990s, something equally unexpected and intriguing happens. Oliveros' music, which had mostly been confined to the fringes of various smaller scenes for decades, is being discovered by labels with a far more diverse outreach. Record companies like Table of the Elements, Important, and Belgium's Sub Rosa are publishing new work or re-issuing out-of-print back-catalog items. On The Beauty Of The Steel Skeleton/Drifting Depths, her work is juxtaposed with that of popular drone master Eleh, while Attention Patterns, a luxurious vinyl box set including works by Oliveros and contemporaries Eliane Radigue and Yoshi Wada, is a magnificent tribute to her oeuvre. Oliveros is recognized as a pioneer, an important presence and as an influence for a generation of musicians, who are working with a strikingly similar aesthetic albeit mostly using different tools — the entire 60-item catalog of the Mystery Sea label, as just one example, seems like a natural extension of Troglodyte's Delight. These are signs that Oliveros' work is not just garnering 'respect' and 'recognition' — the industry's favourite terminology for badly selling outsider material — but real, tangible enthusiasm among a community that, despite its still stark niche status, keeps growing on a global level — and to an extent which that starry-eyed and wonder-eared nine-year-old girl could never have imagined.

* * *

I am not necessarily a historian of music.

I have been around long enough to have my own history. Perhaps my own history from earliest memories of music reflects the kind of unfolding of the history of civilization. Moving from innate rhythmic responses to more and more sophisticated or complicated musical understandings is a process that seems to be repeated in civil life through education. Right now, there are enormous changes that have been seeded by African music that come through popular music and mainly rock and roll. Amplification has enabled crowds to come together around ideas of freedom, such as the Arab Spring. Music has always been a social force. Thus it is a powerful political tool, formerly tightly controlled by governments. Now that any individual has the empowerment through technology to listen to anything they want, the political game has changed. Music is in the ears of the people. Freedom may come through music, not politics. [13]

[1]http://musicmavericks.publicradio.org/features/interview_oliveros.html

[2]http://musicmavericks.publicradio.org/features/interview_oliveros.html

[3]EAR (Magazine of New Music) Volume 12 Number 9, December/January 1988; page 26- excerpts from Meet the Composer: Pauline Oliveros Interview by Peggyann Wachtel

[4]http://www.felbick.de/po5.htmlInterview: Carl Stone interviewing Pauline Oliveros

[5] Pauline Oliveros in conversation with the author, September 2011

[6]http://musicmavericks.publicradio.org/features/interview_oliveros.html

[7] Pauline Oliveros: Sonic Meditation, 1975

[8]http://media.hyperreal.org/zines/est/intervs/oliveros.html

[9] Pauline Oliveros in conversation with the author, September 2011

[10] Pauline Oliveros in conversation with the author, September 2011

[11] Booklet of Attention Patterns (Important, 2010)

[12] Pauline Oliveros in conversation with the author, September 2011

[13] Pauline Oliveros in conversation with the author, September 2011